Recognizing clinical and experimental evidence, physiotherapy is a healthcare profession that helps restore and maintain function to individuals affected by injury, disease or disability by using mechanical force and movements, manual therapy, exercise and electrotherapy, as well as through patient education and advice. The terms physiotherapy and physical therapy are used interchangeably to describe the same healthcare profession. Physiotherapy is recommended for a variety of injuries and conditions, and it can help support overall health and wellness for people of all ages.

For further notice, physiotherapy services may be offered alongside chiropractic care, to provide a cautious and gentle manipulation and/or mobilization of the cervical and thoracic spine in the instance of a large cervical disc herniation. Cervical disc herniations can cause pain and discomfort, numbness and weakness in the neck, shoulders, chest, arms and hands.

Abstract

A 34-year-old woman was seen in a physiotherapy department with signs and symptoms of cervical radiculopathy. Loss of cervical lordosis and a large paracentral to intraforaminal disc prolapse (8 mm) at C5–C6 level was reported on MRI. She was taking diclofenac sodium, tramadol HCl, diazepam and pregabalin for the preceding 2 months and no significant improvement, except temporary relief, was reported. She was referred to physiotherapy while awaiting a surgical opinion from a neurosurgeon. In physiotherapy she was treated with mobilisation of the upper thoracic spine from C7 to T6 level. A cervical extension exercise was performed with prior voluntary extension of the thoracic spine and elevated shoulders. She was advised to continue the same at home. General posture advice was given. Signs and symptoms resolved within the following four sessions of treatment over 3 weeks. Surgical intervention was subsequently deemed unnecessary.

Background

Surgical interventions are commonly recommended in large cervical prolapsed discs and the importance of non-aggressive physiotherapy interventions is less recognised and poorly understood. We present interventions that were associated with resolution of symptoms of radiculopathy resulting from a larger cervical herniated disc. These interventions, if applied correctly, may help to reduce the number of surgeries required for cervical prolapsed discs.

Case Presentation

The patient was a 34-year-old woman. She was seen in the physiotherapy department with a complaint of left-sided neck and shoulder pain. The pain was radiating to her left arm and there was associated numbness. The duration of symptoms was more than 2 months with no history of trauma. The pain was present on waking in the morning and gradually increased during the day. She was otherwise a healthy woman. Neck movements were aggravating the symptoms. She was seen in the acute hospital accident and emergency department (A&E) twice since onset and had been taking diclofenac sodium, tramadol HCl, diazepam and pregabalin. An MRI was planned and a request was sent for physiotherapy during the MRI waiting period. A neurosurgical review was requested by the A&E consultant upon receipt of the MRI report 7 weeks later.

Patient examination in the physiotherapy department revealed a normal gait pattern, her left arm held in front of her chest with the left shoulder slightly elevated. Her active range of neck motion was restricted and was painful on the left side. Flexion and rotation to the left were aggravating her arm and shoulder pain. Strength deficits were noted in the left elbow flexors and wrist extensors (4/5) when compared with the right side. There was paraesthesia along the radial border of the forearm and thumb regions. The brachioradialis reflex was diminished and biceps reflex was sluggish. Triceps and plantar reflexes were normal. Passive intervertebral movements were tender at C5–C6 level and were reproducing the pain. Sustained pressure at C7 and below was easing the pain and also improving the neck range of motion. The patient was deemed to have C6 radiculopathy. The MRI report, available 2 weeks after the commencement of physiotherapy, confirmed the diagnosis.

Investigations

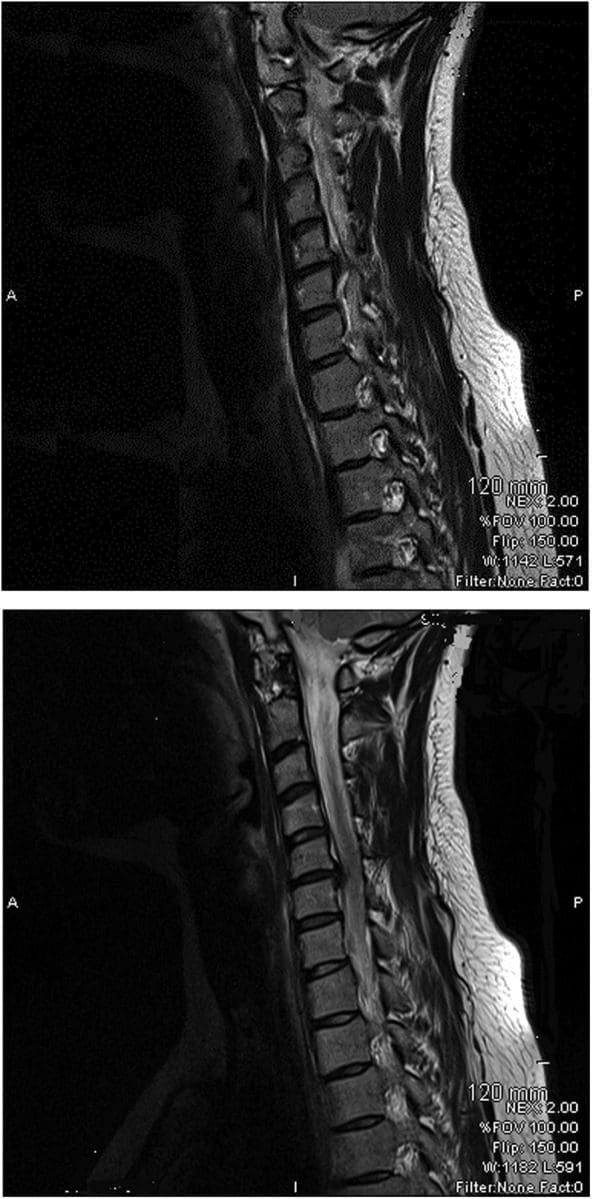

The findings from the plain cervical x-ray were unremarkable. MRI showed (Figure 1) loss of cervical spine lordosis, a left paracentral to intraforaminal lesion with 8 mm hernia, which indented the cord and obstructed the left paracentral recess and neural foramen.

Figure 1: Loss of cervical spine lordosis and large disc herniation at C5 and C6 on MRI.

Differential Diagnosis

- Cervical myelopathy.

Treatment

The patient received pharmacological treatment for the initial two symptomatic months, which included diclofenic sodium, tramadol, diazepam and pregabalin (lyrica) tablet. Physiotherapy was started after 2 months. Physiotherapy intervention consisted of mobilisation of the thoracic spine, resisted cervical extension exercises, a home programme of exercises and advice regarding the posture.

Mobilisation of the thoracic spine was administered in the prone lying position from C7 toT6 level. Mild intensity oscillations (15 reps) in an anterosuperior direction were directly applied to each of the spinal segments, through the thumb over the spinous processes, during the first visit. The applied force was enough to appreciate intervertebral movement in each segment and without significant pain. High-intensity oscillations (10–20) were applied during the subsequent treatment sessions. The patient was asked for symptom feedback during treatment.

Cervical spine extension exercises were carried out in a sitting position. The patient was asked to extend her thoracic spine with lungs fully inflated and shoulders elevated followed by extension of her cervical spine. Head extension was moderately resisted by the therapist near the end range of extension for 5–10 s and brought back to neutral after each resisted movement. The resisted movement was repeated at least three times with intervals of 30 s. The patient was asked to perform the same exercise at home every hour during the day.

The patient was educated regarding the rationale of extension exercises, sitting and lying posture and their effects on the spine. The duration of each session was approximately 20–25 min.

Dr. Alex Jimenez's Insight

Surgical interventions are generally recommended and widely considered for large cervical disc herniations. Although less recognized and often misunderstood, however, physiotherapy can be just as effective towards improving herniated discs in the cervical spine, excluding the need for surgery, according to the research study. Pharmacological treatments are also commonly used to help temporarily reduce symptoms alongside physiotherapy interventions. Cautious and gentle, spinal manipulation and mobilization of the cervical spine should be performed in the case of large cervical disc herniations to avoid aggravating the injury and/or condition. As recommended by a physiotherapist, or other healthcare professional experienced in physiotherapy, proper exercise can restore the function of the cervical spine and prevent regression of large prolapsed discs along the spine. Through appropriate physiotherapy intervention as well as through patient safety and compliance, the retraction of the cervical herniated discs is possible.

Outcome and Follow-Up

Pharmacological interventions were helpful to reduce the patient's pain on a temporary basis. Symptoms were recurring and resolution was not sustainable. The symptoms started improving after the first physiotherapy session and continued to improve during the subsequent sessions. It fully resolved in four sessions extended over 3 weeks. The patient was reviewed 4 months after the resolution of symptoms and there was no recurrence of symptoms. She was reviewed by a neurosurgeon and the surgical option was withdrawn.

Discussion

Stiffness of the thoracic spine has been linked to the painful pathologies of the cervical spine, and manipulation of the thoracic spine has been shown to improve painful symptoms and mobility of the cervical spine. However, cervical disc herniations of greater than 4 mm are considered inappropriate for physiotherapy interventions such as traction and manipulation. Spinal manipulation refers to a passive movement thrust of high velocity and low amplitude, usually applied at the end range of movement and is beyond the patient's control. Manipulation of the cervical spine is an aggressive procedure, which carries various risks and is often associated with worsening of symptoms. Manipulation was not considered in the treatment options for this patient because of the risks associated with it, and also because of patient's anxiety and lack of MRI-confirmed diagnosis.

Active extension of the thoracic spine increases the range of motion of the cervical spine and, in these authors’ clinical experience, relieves minor neck symptoms. Conversely, thoracic spine kyphosis, such as slouch sitting, restricts the mobility of the cervical spine and aggravates the painful symptoms. A good sitting posture is constituted by a slightly extended thoracic spine. Therefore, active extension of the thoracic spine prior to cervical extension may improve cervical movements and restore cervical curvature.

It is believed that excessive pressure during flexion on the anterior aspect of the intervertebral discs pushes the nucleus pulposus posteriorly and causes herniations. Conversely, cervical lordosis might have the reverse effect—that is, decreases pressure on the anterior aspect of the discs and may create a suction effect which retracts the herniated contents. Therefore, a combination of short duration and repeated movements at the end of extension may serve as a suction pump and possibly retract the extruded content of the disc. Active cervical extension exercises, with an extended thoracic spine posture, may have been the key element in a home exercise programme to restore lordosis of the cervical spine and relieve radiculopathy symptoms in the current case. This may possibly have been due to the retraction of the herniated discs.

Spinal mobilisation refers to a gentle, oscillatory, passive movement of a spinal segment. These are applied to a spinal segment to gently increase the passive range of motion. It allows the patient to report aggravation of pain and to resist any unwanted movements. No mobilisation treatment was administered at C5—C6 level as palpation at this level was aggravating the symptoms. Segments below this level were mobilised with emphasis at C7—T1 level. Any treatment at the affected segment was likely to irritate the nerve root and thereby increase the inflammatory process.

Various interventions are reported for the treatment of prolapsed discs. Saal et al reported the use of traction, specific physical therapy exercise, oral anti-inflammatory medication and patient education in the treatment of 26 patients with herniated cervical discs (<4 mm) and reported significant improvement in outcomes for 24 patients. They observed that surgery for disc herniations occurs when a patient has significant myotomal weakness, severe pain or pain that persists beyond an arbitrary conservative treatment period of 2–8 weeks.

Spontaneous regressions of cervical disc protrusions are reported in the literature. However, spontaneous regressions of herniated cervical discs are speculated to be rare. Various factors related to regression are hypothesised and theorised. Pan et al summarised the factors related to the resorption of herniated disc as: the age of the patients; dehydration of the expanded nucleus pulposus; resorption of haematoma; revascularisation; penetration of herniated cervical disc fragments through the posterior longitudinal ligament; size of disc herniations; and existence of cartilage and annulus fibrosus tissue in the herniated material. Some studies on spontaneous regressions of discs reported that the patients were receiving physiotherapy. Physiotherapy interventions are not defined in any of these studies, however. Therefore, it is possible that disc regressions in these studies may be due to similar physiotherapy interventions as described here, or the patients were practising techniques and adopting postures as reported in the current case.

Learning Points

- Thoracic spine mobilisation improves cervical spine biomechanics and can be considered in conjunction with other interventions in all painful conditions of the cervical spine.

- Active extension of the thoracic spine facilitates movements of the cervical spine and may help regression of large prolapsed discs.

- There is a possibility of retraction of herniated cervical discs through appropriate physiotherapy intervention.

- Patient education ensures safety and compliance to therapist advice.

- Meticulous assessment and patient feedback guides the therapist in selection of intensity of mobilisation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

In conclusion, physiotherapy, or physical therapy, is used to treat various injuries, diseases and disabilities, through the use of mechanical force and movements, manual therapy, exercise, electrotherapy, and through patient education and advice to restore and maintain function. As in the case above, physiotherapy can be recommended and considered as treatment before referring to surgical interventions of large cervical disc herniations. Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

References

1. Norlander S, Gustavsson BA, Lindell J, et al. Reduced mobility in the cervico-thoracic motion segment—a risk factor for musculoskeletal neck-shoulder pain: a two-year prospective follow-up study. Scand J Rehabil Med 1997;29:167–74. [PubMed]

2. Walser RF, Meserve BB, Boucher TR. The effectiveness of thoracic spine manipulation for the management of musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Man Manipulative Ther 2009;17:237–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

3. Krauss J, Creighton D, Ely JD, et al. The immediate effects of upper thoracic translatoric spinal manipulation on cervical pain and range of motion: a randomized clinical trial. J Man Manipulative Ther2008;16:93–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

4. Saal JS, Saal JA, Yurth EF. Nonoperative management of herniated cervical intervertebral disc with radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:1877–83. [PubMed]

5. Murphy DR, Beres JL. Cervical myelopathy: a case report of a ‘near-miss’ complication to cervical manipulation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008;31:553–7. [PubMed]

6. Leon-Sanchez A, Cuetter A, Ferrer G. Cervical spine manipulation: an alternative medical procedure with potentially fatal complications. South Med J 2007;100:201–3. [PubMed]

7. Scannell JP, McGill SM. Disc prolapse: evidence of reversal with repeated extension. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:344–50. [PubMed]

8. Gurkanlar D, Yucel E, Er U, et al. Spontaneous regression of cervical disc herniations. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 2006;49:179–83. [PubMed]

9. Mochida K, Komori H, Okawa A, et al. Regression of cervical disc herniation observed on magnetic resonance images. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:990–5; discussion 6–7. [PubMed]

10. Song JH, Park HK, Shin KM. Spontaneous regression of a herniated cervical disc in a patient with myelopathy. Case report. J Neurosurg 1999;90(1 Suppl):138–40. [PubMed]

11. Westmark RM, Westmark KD, Sonntag VK. Disappearing cervical disc. Case report. J Neurosurg1997;86:289–90. [PubMed]

12. Pan H, Xiao LW, Hu QF. Spontaneous regression of herniated cervical disc fragments and its clinical significance. Orthop Surg 2010;2:77–9. [PubMed]

13. Teplick JG, Haskin ME. Spontaneous regression of herniated nucleus pulposus. AJR Am J Roentgenol1985;145:371–5. [PubMed]

Additional Topics: Sciatica

Sciatica is referred to as a collection of symptoms rather than a single type of injury or condition. The symptoms are characterized as radiating pain, numbness and tingling sensations from the sciatic nerve in the lower back, down the buttocks and thighs and through one or both legs and into the feet. Sciatica is commonly the result of irritation, inflammation or compression of the largest nerve in the human body, generally due to a herniated disc or bone spur.