In part one of this ‘Rehabilitation Masterclass’ article, chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez evaluates the post- operative rehab requirements following a unique ACL reconstruction method – a Ligament Advanced Reinforcement System (LARS) procedure…

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture is a common injury suffered by many athletes in a variety of sports. It typically affects athletes involved in sports that require sharp deceleration and cutting/pivoting type movements such as all the football sports (soccer, rugby, AFL, NFL), basketball, netball, golf and tennis. It may also occur as the result of a direct blow to the outside of the knee, which causes a valgus knee collapse, imposing large tensile and torsional forces to both the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and ACL.

It has been estimated that 80% of all ligament reconstructions of the knee relate to the ACL(1). It is accepted that ACL ruptures have poor intrinsic healing capabilities due to the fact that the ACL is enveloped by synovial fluid and lacks significant vascularisation(2). This makes healing of this intra-articular ligament impossible due to the inability of the torn ligament to re-vascularize.

In many case therefore, this precipitates the need to reconstruct the ACL to achieve functional stability to withstand anteroposterior shear forces and to prevent rotational forces on the knee. This course of action will prevent any further meniscus breakdown, and early onset osteoarthritis due to the excessive shearing forces encountered by the ACL deficient knee(3,4).

Surgical techniques vary from surgeon to surgeon and from country to country. Indeed, it is not uncommon for two orthopedic surgeons from the same sports medicine clinic to differ in their surgical choices. The options the surgeon has include:

1. Arthroscopic versus open surgery.

2. Intra versus extra-articular reconstruction.

3. Femoral tunnel placement.

4. Number of graft strands.

5. Single versus double bundle.

6. Fixation methods.

The use of grafts falls into three different subtypes:

1. Autologous grafts such as the patella- bone-patella (PTB) graft and the quadruple gracilis/hamstring graft techniques. These are the most commonly used as the graft is taken from the patient thus eliminating the risk of graft rejection(5). The major drawback of these grafts is possible donor site problems and the length of time it takes for the graft to re-vascularise (6-9 months)(6).2. Allografts are harvested from a human tissue bank and the common allograft tendons to use are tibialis posterior, Achilles tendon or peroneus tendon and hamstring. The benefit is that there is no donor site morbidity at the knee. However the risk of graft rejection is quite high, the recovery rate is longer, post-operative infections more common and there are higher failure rates(5,6).

3. Synthetic grafts using Polyethylene Terephthalate, Polypropylene, Polytetrafluroethene (PTFE), Carbon Fibre or Dacron. The original grafts used in the 1980s had high rates of failure and reactive synovitis so they fell out of favour(7).

However synthetic grafts are now in their third generation and in the last 20 years the Ligament Advanced Reinforcement System (LARS) procedure has gained more popularity with orthopaedists(8).

What Is The LARS Procedure?

The LARS system was developed in France by a French surgeon called Professor JP Laboreau. This was developed over a lengthy period of time, finding a material and technique that would prevent the failure rates seen with other synthetic grafts, and to also avoid the morbidity seen with human tissue grafts involving the patella tendon and hamstring grafts.LARS has been used successfully to reconstruct ACL ruptures in countries such as Australia, United Kingdom, France, Germany and Canada. However, the United States has still not approved the use of LARS in the USA, with the result thatAmericanathletesoftenseeksurgical treatment in other countries.

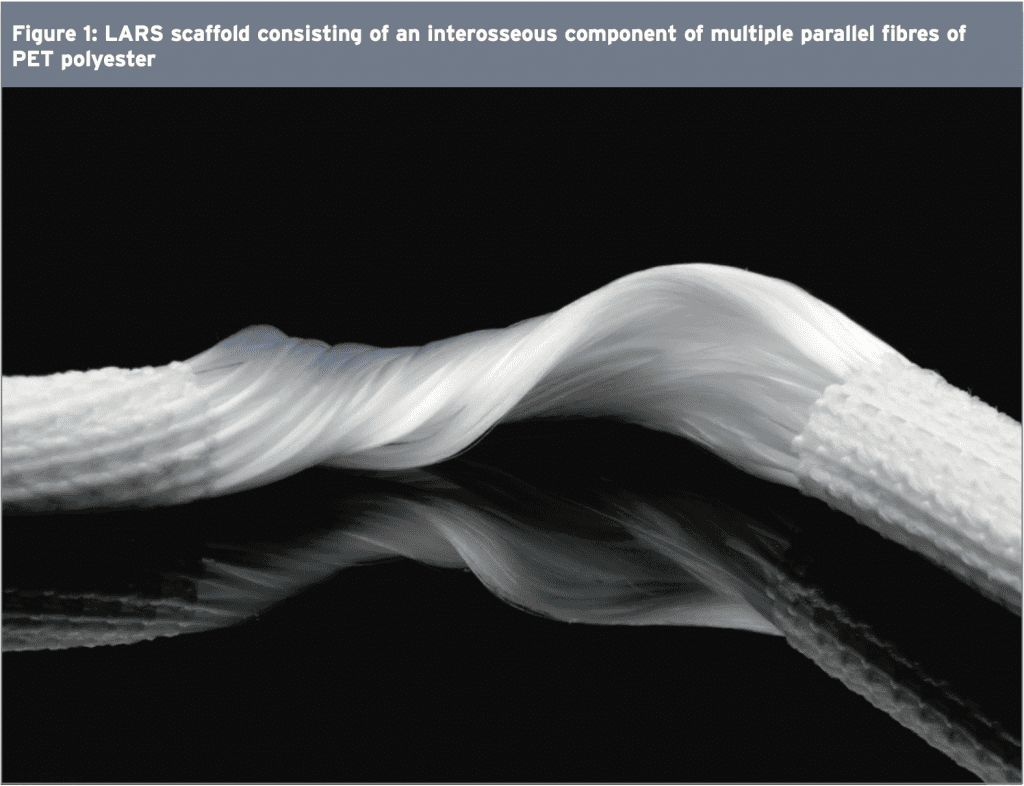

A LARS is an intra-articular scaffold consisting of an interosseous component of multiple parallel fibres of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) polyester (see Figure 1). The intra-articular segment is unique and different to other synthetic grafts in that it is twisted at 90 degree angles.

Biomechanically, this artificial ligament mimics the natural ligamentous structure of the ACL and this design reduces shearing forces by specifically orientating the intra-articular fibres either clockwise for right knees or counter- clockwise for left knees. The porous nature of the PET fibres allow ingrowth from surrounding osseous tunnels and the remaining ACL stump. The ingrowth of the tissues into this scaffold gives the graft greater viscoelasticity and also protects against friction at the opening of the bony canal and between the fibres themselves(2).

The LARS artificial ligament is sterilized and chemically treated to remove any potential machining residues. Also, the emulsion of fat enzymes that may prevent soft tissue ingrowth and the sterility reduces the risk of reactive synovitis and fibre breakdown associated with other synthetic grafts(7,910).

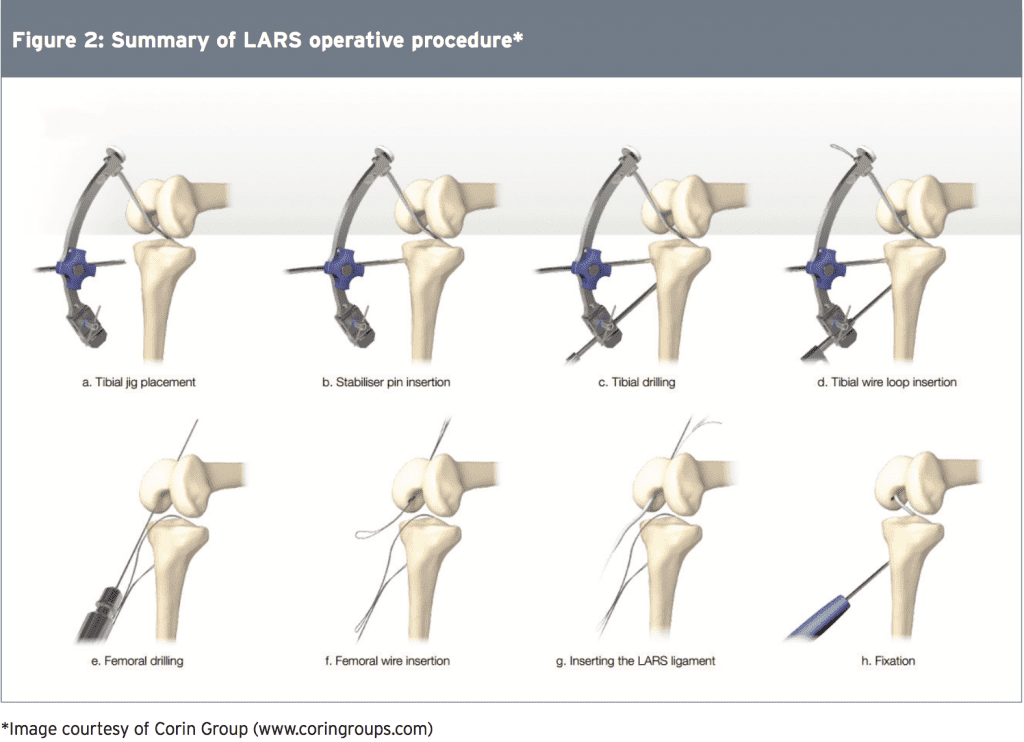

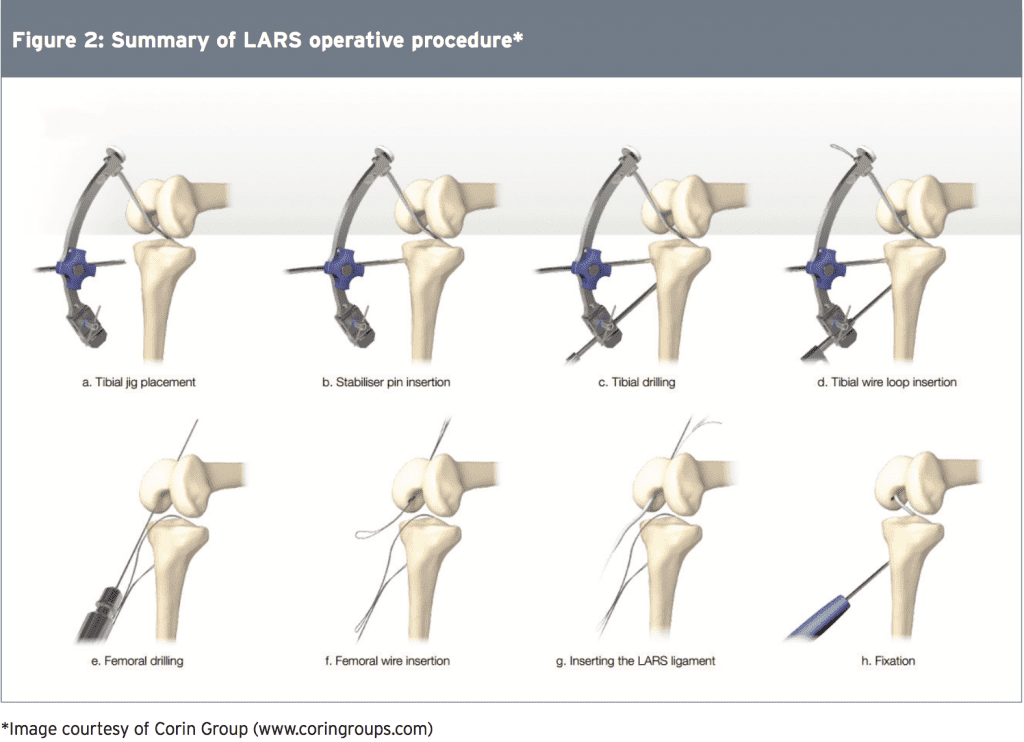

In a LARS procedure, the synovial lining and the torn ACL fibres are left intact, whereas in other ACL reconstructive procedures the ACL is debrided to allow osseous tunnel drilling for the autologous graft. The osseous tunnels are positioned under image intensifier x-ray and this allows the torn ACL stump to remain. The proposed advantage of this technique is reduced trauma to the soft tissues of the knee and less surgical time(8). The remaining ACL stump is anchored to the meshwork of the LARS to support it in an optimum position while healing. Figure 2 shows a summary of a typical LARS operative procedure.

Overall, the LARS surgical technique aims to maximize in-growth of the original ACL tissue, thus preserving some vascular and proprioceptive nerve supply. The biggest advantages of this procedure are immediate graft stability, reduced rehabilitation time and quicker return to pre-injury function. Over time, the existing ACL stump regrows into the matrix and eventually replaces the LARS. Therefore it is not used a stand- alone graft. It has been proposed that the benefit of the LARS procedure is that it allows early post-operative loading because the scaffold protects the ACL stump during its revascularization phase, with less chance of post-operative breakdown(6).

The biggest potential problem faced when using a LARS procedure is the quality of the remaining ACL stump(8). A viable stump is needed to allow new ligamentous tissue, and surgery needs to occur as soon as possible after injury to preserve the native ACL stump(11). Therefore, the LARS reconstruction may be best suited to patients with acute ruptures who possess a viable cruciate stump. This allows the ligamentous and neurovascular tissues to regenerate along the synthetic scaffold. Furthermore, placement and tensioning of the LARS is crucial to prevent failure, emphasizing the need for an experienced surgeon to perform this procedure. Finally, it may not be appropriate in ACL ruptured knees that have co-existing pathologies such as large meniscal tears or osteochondral defects; these patients are generally delayed in return to sport, making the benefit of the fast return with LARS pointless.

References

1. J Sci Med Sport 2009, 12:622-627

2. World J Orthop. 2015 Jan 18; 6(1): 127–136

3. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2008; 69: 459-60, 462-463

4. Am J Sports Med 2006, 34(12):2026-37

5. J Arthroscopic & Related Surg 2009, 25(9):1006-1010

6. J Arthroscopic & Related Surg 2009, 25(6):653-85

7. Eur Surg Res 2004, 36:148-151

8. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine 1995, 3(3):187-20

9. British Medical Bulletin 2010, 1-24

10. Chin Med J 2010, 123(2):160-164

11. Knee surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2010. 18, 797-804

12. Int Orthop 2013; 37: 321-326

13. J Arthroscopic & Related Surg 2010, 26(4):515-523

14. International Orthopaedics. 2010, Jan; 34(1): 45–49

15. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84: 356-360

16.Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2013; 23: 819-823

Overall, the LARS surgical technique aims to maximize in-growth of the original ACL tissue, thus preserving some vascular and proprioceptive nerve supply. The biggest advantages of this procedure are immediate graft stability, reduced rehabilitation time and quicker return to pre-injury function. Over time, the existing ACL stump regrows into the matrix and eventually replaces the LARS. Therefore it is not used a stand- alone graft. It has been proposed that the benefit of the LARS procedure is that it allows early post-operative loading because the scaffold protects the ACL stump during its revascularization phase, with less chance of post-operative breakdown(6).

The biggest potential problem faced when using a LARS procedure is the quality of the remaining ACL stump(8). A viable stump is needed to allow new ligamentous tissue, and surgery needs to occur as soon as possible after injury to preserve the native ACL stump(11). Therefore, the LARS reconstruction may be best suited to patients with acute ruptures who possess a viable cruciate stump. This allows the ligamentous and neurovascular tissues to regenerate along the synthetic scaffold. Furthermore, placement and tensioning of the LARS is crucial to prevent failure, emphasizing the need for an experienced surgeon to perform this procedure. Finally, it may not be appropriate in ACL ruptured knees that have co-existing pathologies such as large meniscal tears or osteochondral defects; these patients are generally delayed in return to sport, making the benefit of the fast return with LARS pointless.

Summary

Part one of this 2-part Rehabilitation Masterclass has focused on the innovative (and at times controversial) LARS procedure as a means of reconstructing the ruptured ACL. It is still a relatively new procedure that lacks long-term follow-up studies assessing success and failure rates c o m p a r e d t o t r a d i t i o n a l A C L reconstruction. Due to the unique synthetic properties of the LARS, it is proposed that athletes will return to competition much faster than with traditional ACL reconstruction. Therefore, the post-operative rehabilitation will differ significantly in both time and content compared with the traditional ACL reconstruction. Part two of this article therefore discusses in depth the postoperative process following a LARS reconstruction.References

1. J Sci Med Sport 2009, 12:622-627

2. World J Orthop. 2015 Jan 18; 6(1): 127–136

3. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2008; 69: 459-60, 462-463

4. Am J Sports Med 2006, 34(12):2026-37

5. J Arthroscopic & Related Surg 2009, 25(9):1006-1010

6. J Arthroscopic & Related Surg 2009, 25(6):653-85

7. Eur Surg Res 2004, 36:148-151

8. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine 1995, 3(3):187-20

9. British Medical Bulletin 2010, 1-24

10. Chin Med J 2010, 123(2):160-164

11. Knee surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2010. 18, 797-804

12. Int Orthop 2013; 37: 321-326

13. J Arthroscopic & Related Surg 2010, 26(4):515-523

14. International Orthopaedics. 2010, Jan; 34(1): 45–49

15. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002; 84: 356-360

16.Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2013; 23: 819-823