Chiropractic care is a well-known alternative treatment option commonly used for a variety of injuries and/or conditions, including low back pain and sciatica. Of course, not all pain is physical nor does it always have a physical cause. Stress, anxiety and depression affects millions of people each year. While many patients require prescription drug therapy to treat their mental health issues, others may be able to control and treat they symptoms with a holistic approach. Chiropractic care is an effective stress management treatment which can help reduce symptoms associated with stress, such as low back pain and sciatica.

How Does Stress Affect the Body?

There are 3 major categories of stress: bodily, environmental and emotional.

- Bodily stress: Caused by lack of sleep, disease, trauma or injury, and an improper nutrition.

- Environmental stress: Caused by loud noises (sudden or sustained), pollution and world events, such as war and politics.

- Emotional stress: Caused by a variety of life events, such as moving homes, starting a new job and regular personal interactions. In contrast to the other two categories of stress, however, people can have some control over their emotional stress. Such can depend on the individual's own attitude.

Stress can affect the human body in a variety of ways, both positively and negatively, physically and emotionally. Although short-term stress can be helpful, long-term stress can cause many cumulative health issues on both the mind and body. Stress activates the "fight or flight" response, a defense mechanism triggered by the sympathetic nervous system to prepare the body for perceived danger by increasing heart rate and breathing as well as the senses, by way of instance, eyesight can become more acute. Once the stressor goes away, the central nervous system relays the message to the body and the vitals return to normal.

In several instances, the central nervous system can fail to relay the signal to the body when it is time to return to its relaxed state. Many people also experience persistent, recurrent stress, referred to as chronic stress. Either occurrence takes a toll on the human body. This type of stress can often lead to pain, anxiety, irritability and depression.

Managing Your Stress

Chronic stress can cause painful symptoms, such as low back pain and sciatica, which can then cause more stress. Pain generally contributes to mood issues, such as anxiety and depression, clouded thought processes, and an inability to concentrate. Individuals with chronic stress who experience painful symptoms may feel unable to perform and engage in regular activities.

Stress management treatment can help people improve as well as manage their chronic stress and its associated symptoms. Chiropractic care can help reduce pain and muscle tension, further decreasing stress. The central nervous system can also benefit from the effects of chiropractic treatment. The central nervous system, or CNS, helps regulate mood, as well as full-body health and wellness, meaning that a balanced central nervous system can help enhance overall well-being.

Benefits of Chiropractic Care

Chiropractic care is a holistic treatment approach, designed to return the body to the original state it needs to maintain the muscles and joints functioning properly. Chronic stress can cause muscle tension along the back, which can eventually lead to spinal misalignments. A misalignment of the spine, or a subluxation, can contribute to a variety of symptoms, including nausea and vomiting, headaches and migraines, stress and digestive issues. A chiropractor utilized spinal adjustments and manual manipulations to release pressure and decrease the inflammation around the spine to improve nerve function and allow the body to heal itself naturally. Alleviating pain can ultimately help decrease stress and enhance overall health and wellness. Chiropractic care can also include massage as well as counseling to help control stress, anxiety and depression.

A Holistic Care Approach

Most chiropractors will utilize other treatment methods and techniques, such as physical therapy, exercise, and nutrition advice, to further increase the stress management effects of chiropractic care. These lifestyle changes affect every area of your well-being. Furthermore, the purpose of the article below is to demonstrate the effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction compared to cognitive-behavioral therapy and usual care on stress with associated symptoms of chronic low back pain and sciatica.

Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Usual Care on Back Pain and Functional Limitations among Adults with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

Importance

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has not been rigorously evaluated for young and middle-aged adults with chronic low back pain.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness for chronic low back pain of MBSR versus usual care (UC) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized, interviewer-blind, controlled trial in integrated healthcare system in Washington State of 342 adults aged 20–70 years with CLBP enrolled between September 2012 and April 2014 and randomly assigned to MBSR (n = 116), CBT (n = 113), or UC (n = 113).

Interventions

CBT (training to change pain-related thoughts and behaviors) and MBSR (training in mindfulness meditation and yoga) were delivered in 8 weekly 2-hour groups. UC included whatever care participants received.

Main Outcomes and Measures

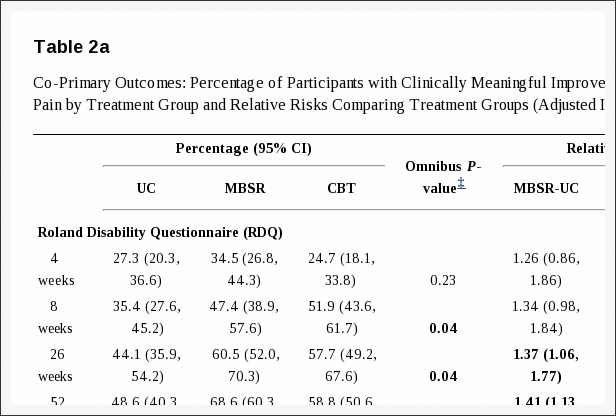

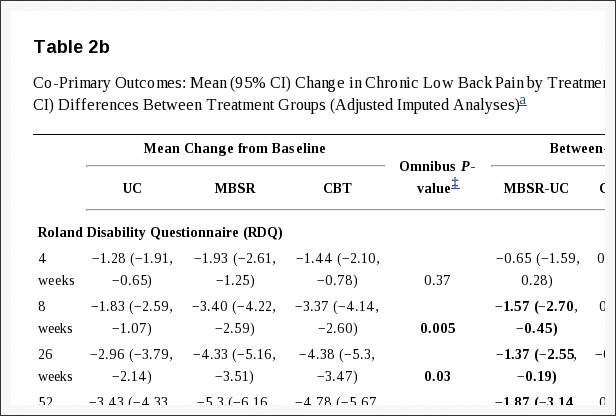

Co-primary outcomes were the percentages of participants with clinically meaningful (≥30%) improvement from baseline in functional limitations (modified Roland Disability Questionnaire [RDQ]; range 0 to 23) and in self-reported back pain bothersomeness (0 to 10 scale) at 26 weeks. Outcomes were also assessed at 4, 8, and 52 weeks.

Results

Among 342 randomized participants (mean age, 49 (range, 20–70); 225 (66%) women; mean duration of back pain, 7.3 years (range 3 months to 50 years), <60% attended 6 or more of the 8 sessions, 294 (86.0%) completed the study at 26 weeks and 290 (84.8%) completed the study 52weeks. In intent-to-treat analyses, at 26 weeks, the percentage of participants with clinically meaningful improvement on the RDQ was higher for MBSR (61%) and CBT (58%) than for UC (44%) (overall P = 0.04; MBSR versus UC: RR [95% CI] = 1.37 [1.06 to 1.77]; MBSR versus CBT: 0.95 [0.77 to 1.18]; CBT versus UC: 1.31 [1.01 to 1.69]. The percentage of participants with clinically meaningful improvement in pain bothersomeness was 44% in MBSR and 45% in CBT, versus 27% in UC (overall P = 0.01; MBSR versus UC: 1.64 [1.15 to 2.34]; MBSR versus CBT: 1.03 [0.78 to 1.36]; CBT versus UC: 1.69 [1.18 to 2.41]). Findings for MBSR persisted with little change at 52 weeks for both primary outcomes.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among adults with chronic low back pain, treatment with MBSR and CBT, compared with UC, resulted in greater improvement in back pain and functional limitations at 26 weeks, with no significant differences in outcomes between MBSR and CBT. These findings suggest that MBSR may be an effective treatment option for patients with chronic low back pain.

Introduction

Low back pain is a leading cause of disability in the U.S. [1]. Despite numerous treatment options and greatly increased medical care resources devoted to this problem, the functional status of persons with back pain in the U.S. has deteriorated [2, 3]. There is need for treatments with demonstrated effectiveness that are low-risk and have potential for widespread availability.

Psychosocial factors play important roles in pain and associated physical and psychosocial disability [4]. In fact, 4 of the 8 non-pharmacologic treatments recommended for persistent back pain include “mind-body” components [4]. One of these, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), has demonstrated effectiveness for various chronic pain conditions [5–8] and is widely recommended for patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP). However, patient access to CBT is limited. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) [9], another “mind-body” approach, focuses on increasing awareness and acceptance of moment-to-moment experiences, including physical discomfort and difficult emotions. MBSR is becoming increasingly popular and available in the U.S. Thus, if demonstrated beneficial for CLBP, MBSR could offer another psychosocial treatment option for the large number of Americans with this condition. MBSR and other mindfulness-based interventions have been found helpful for a range of conditions, including chronic pain [10–12]. However, only one large randomized clinical trial (RCT) has evaluated MBSR for CLBP [13], and that trial was limited to older adults.

This RCT compared MBSR with CBT and usual care (UC). We hypothesized that adults with CLBP randomized to MBSR would show greater short- and long-term improvement in back pain-related functional limitations, back pain bothersomeness, and other outcomes, as compared with those randomized to UC. We also hypothesized that MBSR would be superior to CBT because it includes yoga, which has been found effective for CLBP [14].

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Participants

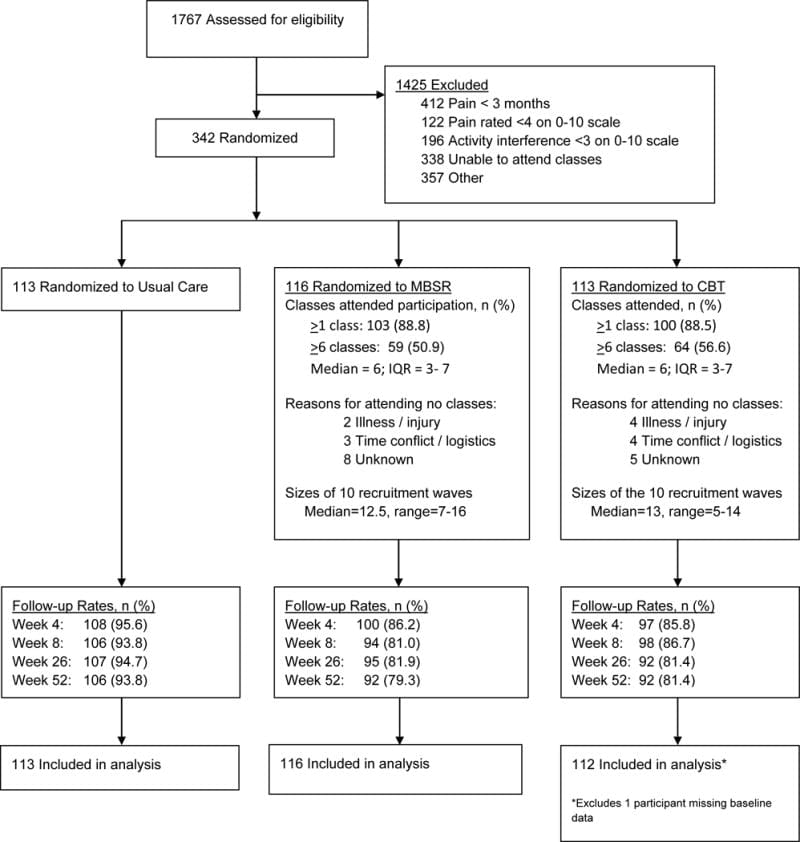

We previously published the Mind-Body Approaches to Pain (MAP) trial protocol [15]. The primary source of participants was Group Health (GH), a large integrated healthcare system in Washington State. Letters describing the trial and inviting participation were mailed to GH members who met the electronic medical record (EMR) inclusion/exclusion criteria, and to random samples of residents in communities served by GH. Individuals who responded to the invitations were screened and enrolled by telephone (Figure 1). Potential participants were told that they would be randomized to one of “two different widely-used pain self-management programs that have been found helpful for reducing pain and making it easier to carry out daily activities” or to continued usual care plus $50. Those assigned to MBSR or CBT were not informed of their treatment allocation until they attended the first session. We recruited participants from 6 cities in 10 separate waves.

Figure 1: Flow of participants through trial comparing mindfulness-based stress reduction with cognitive-behavioral therapy and usual care for chronic low back pain.

We recruited individuals 20 to 70 years of age with non-specific low back pain persisting at least 3 months. Persons with back pain associated with a specific diagnosis (e.g., spinal stenosis), with compensation or litigation issues, who would have difficulty participating (e.g., unable to speak English, unable to attend classes at the scheduled time and location), or who rated pain bothersomeness <4 and/or pain interference with activities <3 on 0–10 scales were excluded. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were assessed using EMR data for the previous year (for GH enrollees) and screening interviews. Participants were enrolled between September 2012 and April 2014. Due to slow enrollment, after 99 participants were enrolled, we stopped excluding persons 64–70 years old, GH members without recent visits for back pain, and patients with sciatica. The trial protocol was approved by the GH Human Subjects Review Committee. All participants gave informed consent.

Randomization

Immediately after providing consent and completing the baseline assessment, participants were randomized in equal proportions to MBSR, CBT, or UC. Randomization was stratified by the baseline score (≤12 versus ≥13, 0–23 scale) of one of the primary outcome measures, the modified Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) [16]. Participants were randomized within these strata in blocks of 3, 6, or 9. The stratified randomization sequence was generated by the study biostatistician using R statistical software [17], and the sequence was stored in the study recruitment database and concealed from study staff until randomization.

Interventions

All participants received any medical care they would normally receive. Those randomized to UC received $50 but no MBSR training or CBT as part of the study and were free to seek whatever treatment, if any, they desired.

The interventions were comparable in format (group), duration (2 hours/week for 8 weeks, although the MBSR program also included an optional 6-hour retreat), frequency (weekly), and number of participants per group [See reference 15 for intervention details]. Each intervention was delivered according to a manualized protocol in which all instructors were trained. Participants in both interventions were given workbooks, audio CDs, and instructions for home practice (e.g., meditation, body scan, and yoga in MBSR; relaxation and imagery in CBT). MBSR was delivered by 8 instructors with 5 to 29 years of MBSR experience. Six of the instructors had received training from the Center for Mindfulness at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. CBT was delivered by 4 licensed Ph.D.-level psychologists experienced in group and individual CBT for chronic pain. Checklists of treatment protocol components were completed by a research assistant at each session and reviewed weekly by a study investigator to ensure all treatment components were delivered. In addition, sessions were audio-recorded and a study investigator monitored instructors’ adherence to the protocol in person or via audio-recording for at least one session per group.

MBSR was modelled closely after the original MBSR program [9], with adaptation of the 2009 MBSR instructor’s manual [18] by a senior MBSR instructor. The MBSR program does not focus specifically on a particular condition such as pain. All classes included didactic content and mindfulness practice (body scan, yoga, meditation [attention to thoughts, emotions, and sensations in the present moment without trying to change them, sitting meditation with awareness of breathing, walking meditation]). The CBT protocol included CBT techniques most commonly applied and studied for CLBP [8, 19–22]. The intervention included (1) education about chronic pain, relationships between thoughts and emotional and physical reactions, sleep hygiene, relapse prevention, and maintenance of gains; and (2) instruction and practice in changing dysfunctional thoughts, setting and working towards behavioral goals, relaxation skills (abdominal breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery), activity pacing, and pain coping strategies. Between-session activities included reading chapters of The Pain Survival Guide [21]. Mindfulness, meditation, and yoga techniques were proscribed in CBT; methods to challenge dysfunctional thoughts were proscribed in MBSR.

Follow-Up

Trained interviewers masked to treatment group collected data by telephone at baseline (before randomization) and 4 (mid-treatment), 8 (post-treatment), 26 (primary endpoint), and 52 weeks post-randomization. Participants were compensated $20 for each interview.

Measures

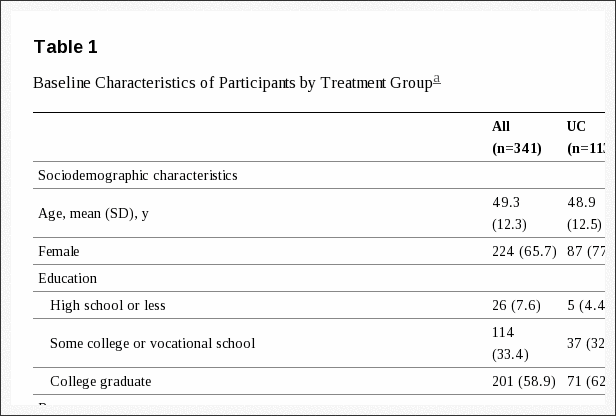

Sociodemographic and back pain information was obtained at baseline (Table 1). All primary outcome measures were administered at each time-point; secondary outcomes were assessed at all time-points except 4 weeks.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of participants by treatment group.

Co–primary Outcomes

Back pain-related functional limitation was assessed by the RDQ [16], modified to 23 (versus the original 24) items and to ask about the past week rather than today only. Higher scores (range 0–23) indicate greater functional limitation. The original RDQ has demonstrated reliability, validity, and sensitivity to clinical change [23]. Back pain bothersomeness in the past week was measured by a 0–10 scale (0 = “not at all bothersome,” 10 = “extremely bothersome”). Our primary analyses examined the percentages of participants with clinically meaningful improvement (≥30% improvement from baseline) [24] on each measure. Secondary analyses compared the adjusted mean change from baseline between groups.

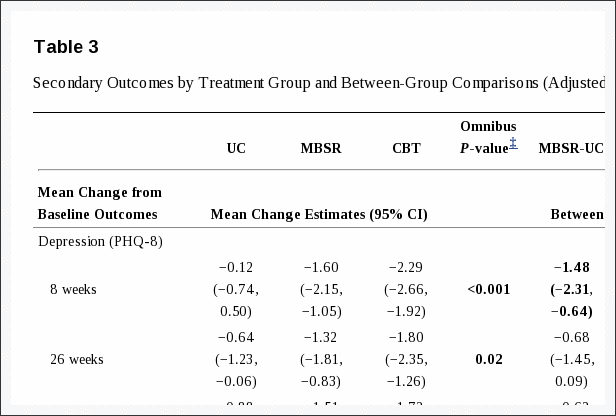

Secondary Outcomes

Depressive symptoms were assessed by the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8; range, 0–24; higher scores indicate greater severity) [25]. Anxiety was measured using the 2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-2; range, 0–6; higher scores indicate greater severity) [26]. Characteristic pain intensity was assessed as the mean of three 0–10 ratings (current back pain and worst and average back pain in the previous month; range, 0–10; higher scores indicate greater intensity) from the Graded Chronic Pain Scale [27]. The Patient Global Impression of Change scale [28] asked participants to rate their improvement in pain on a 7-point scale (“completely gone, much better, somewhat better, a little better, about the same, a little worse, and much worse”). Physical and mental general health status were assessed with the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) (0–100 scale; lower scores indicate poorer health status) [29]. Participants were also asked about their use of medications and exercise for back pain during the previous week.

Adverse Experiences

Adverse experiences were identified during intervention sessions and by follow-up interview questions about significant discomfort, pain, or harm caused by the intervention.

Sample Size

A sample size of 264 participants (88 in each group) was chosen to provide adequate power to detect meaningful differences between MBSR and CBT and UC at 26 weeks. Sample size calculations were based on the outcome of clinically meaningful improvement (≥30% from baseline) on the RDQ [24]. Estimates of clinically meaningful improvement in the intervention and UC groups were based on unpublished analyses of data from our previous trial of massage for CLBP in a similar population [30]. This sample size provided adequate power for both co-primary outcomes. The planned sample size provided 90% power to detect a 25% difference between MBSR and UC in the proportion with meaningful improvement on the RDQ, and ≥80% power to detect a 20% difference between MBSR and CBT, assuming 30% of UC participants and 55% of CBT participants showed meaningful improvement. For meaningful improvement in pain bothersomeness, the planned sample size provided ≥80% power to detect a 21.8% difference between MBSR and UC, and a 16.7% difference between MBSR and CBT, assuming 47.5% in UC and 69.3% in CBT showed meaningful improvement.

Allowing for an 11% loss to follow-up, we planned to recruit 297 participants (99 per group). Because observed follow-up rates were lower than expected, an additional wave was recruited. A total of 342 participants were randomized to achieve a target sample size of 264 with complete outcome data at 26 weeks.

Statistical Analysis

Following the pre-specified analysis plan [15], differences among the three groups on each primary outcome were assessed by fitting a regression model that included outcome measures from all four time-points after baseline (4, 8, 26, and 52 weeks). A separate model was fit for each co-primary outcome (RDQ and bothersomeness). Indicators for time-point, randomization group, and the interactions between these variables were included in each model to estimate intervention effects at each time-point. Models were fit using generalized estimating equations (GEE) [31], which accounted for possible correlation within individuals. For binary primary outcomes, we used a modified Poisson regression model with a log link and robust sandwich variance estimator [32] to estimate relative risks. For continuous measures, we used linear regression models to estimate mean change from baseline. Models adjusted for age, sex, education, pain duration (<1 year versus ≥1 year since experiencing a week without back pain), and the baseline score on the outcome measure. Evaluation of secondary outcomes followed a similar analytic approach, although models did not include 4-week scores because secondary outcomes were not assessed at 4 weeks.

We evaluated the statistical significance of intervention effects at each time-point separately. We decided a priori to consider MBSR successful only if group differences were significant at the 26-week primary endpoint. To protect against multiple comparisons, we used the Fisher protected least-significant difference approach [33], which requires that pairwise treatment comparisons are made only if the overall omnibus test is statistically significant.

Because our observed follow-up rates differed across intervention groups and were lower than anticipated (Figure 1), we used an imputation method for non-ignorable nonresponse as our primary analysis to account for possible non-response bias. The imputation method used a pattern mixture model framework using a 2-step GEE approach [34]. The first step estimated the GEE model previously outlined with observed outcome data adjusting for covariates, but further adjusting for patterns of non-response. We included the following missing pattern indicator variables: missing one outcome, missing one outcome and assigned CBT, missing one outcome and assigned MBSR, and missing ≥2 outcomes (no further interaction with group was included because very few UC participants missed ≥2 follow-up time-points). The second step estimated the GEE model previously outlined, but included imputed outcomes from step 1 for those with missing follow-up times. We adjusted the variance estimates to account for using imputed outcome measures for unobserved outcomes.

All analyses followed an intention-to-treat approach. Participants were included in the analysis by randomization assignment, regardless of level of intervention participation. All tests and confidence intervals were 2-sided and statistical significance was defined as a P-value ≤ 0.05. All analyses were performed using the statistical package R version 3.0.2 [17].

Results

Figure 1 depicts participant flow through the study. Among 1,767 individuals expressing interest in study participation and screened for eligibility, 342 were enrolled and randomized. The main reasons for exclusion were inability to attend treatment sessions, pain lasting <3 months, and minimal pain bothersomeness or interference with activities. All but 7 participants were recruited from GH. Almost 90% of participants randomized to MBSR and CBT attended at least 1 session, but only 51% in MBSR and 57% in CBT attended at least 6 sessions. Only 26% of those randomized to MBSR attended the 6-hour retreat. Overall follow-up response rates ranged from 89.2% at 4 weeks to 84.8% at 52 weeks, and were higher in the UC group.

At baseline, treatment groups were similar in sociodemographic and pain characteristics except for more women in UC and fewer college graduates in MBSR (Table 1). Over 75% reported at least one year since a week without back pain and most reported pain on at least 160 of the previous 180 days. The mean RDQ score (11.4) and pain bothersomeness rating (6.0) indicated moderate levels of severity. Eleven percent reported using opioids for their pain in the past week. Seventeen percent had at least moderate levels of depression (PHQ-8 scores ≥10) and 18% had at least moderate levels of anxiety (GAD-2 scores ≥3).

Co-Primary Outcomes

At the 26-week primary endpoint, the groups differed significantly (P = 0.04) in percent with clinically meaningful improvement on the RDQ (MBSR 61%, UC 44%, CBT 58%; Table 2a). Participants randomized to MBSR were more likely than those randomized to UC to show meaningful improvement on the RDQ (RR = 1.37; 95% CI, 1.06–1.77), but did not differ significantly from those randomized to CBT. The overall difference among groups in clinically meaningful improvement in pain bothersomeness at 26 weeks was also statistically significant (MBSR 44%, UC 27%, CBT 45%; P = 0.01). Participants randomized to MBSR were more likely to show meaningful improvement when compared with UC (RR = 1.64; 95% CI, 1.15–2.34), but not when compared with CBT (RR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.78–1.36). The significant differences between MBSR and UC, and non-significant differences between MBSR and CBT, in percent with meaningful function and pain improvement persisted at 52 weeks, with relative risks similar to those at 26 weeks (Table 2a). CBT was superior to UC for both primary outcomes at 26, but not 52, weeks. Treatment effects were not apparent before end of treatment (8 weeks). Generally similar results were found when the primary outcomes were analyzed as continuous variables, although more differences were statistically significant at 8 weeks and the CBT group improved more than the UC group at 52 weeks (Table 2b).

Table 2A: Co-primary outcomes: Percentage of participants with clinically meaningful improvement in chronic low back pain by treatment group and relative risks comparing treatment groups (Adjusted Imputed Analyses).

Table 2B: Co-primary outcomes: Mean (95% CI) change in chronic low back pain by treatment group and mean (95% CI) differences between treatment groups (Adjusted Imputed Analyses).

Secondary Outcomes

Mental health outcomes (depression, anxiety, SF-12 Mental Component) differed significantly across groups at 8 and 26, but not 52, weeks (Table 3). Among these measures and time-points, participants randomized to MBSR improved more than those randomized to UC only on the depression and SF-12 Mental Component measures at 8 weeks. Participants randomized to CBT improved more than those randomized to MBSR on depression at 8 weeks and anxiety at 26 weeks, and more than the UC group at 8 and 26 weeks on all three measures.

Table 3: Secondary outcomes by treatment group and between-group comparisons (Adjusted Imputed Analyses).

The groups differed significantly in improvement in characteristic pain intensity at all three time-points, with greater improvement in MBSR and CBT than in UC and no significant difference between MBSR and CBT. No overall differences in treatment effects were observed for the SF-12 Physical Component score or self-reported use of medications for back pain. Groups differed at 26 and 52 weeks in self-reported global improvement, with both the MBSR and CBT groups reporting greater improvement than the UC group, but not differing significantly from each other.

Adverse Experiences

Thirty of the 103 (29%) participants attending at least 1 MBSR session reported an adverse experience (mostly temporarily increased pain with yoga). Ten of the 100 (10%) participants who attended at least one CBT session reported an adverse experience (mostly temporarily increased pain with progressive muscle relaxation). No serious adverse events were reported.

Dr. Alex Jimenez's Insight

Stress management treatment includes a combination of stress management methods and techniques as well as lifestyle changes to help improve and manage stress and its associated symptoms. Because every person responds to stress in a wide variety of ways, treatment for stress will often vary greatly depending on the specific symptoms the individual is experiencing and according to their grade of severity. Chiropractic care is an effective stress management treatment which helps reduce chronic stress and its associated symptoms by reducing pain and muscle tension on the structures surrounding the spine. A spinal misalignment, or subluxation, can create stress and other symptoms, such as low back pain and sciatica. Furthermore, the results of the article above demonstrated that mindfulness-based stress reduction, or MBSR, is an effective stress management treatment for adults with chronic low back pain.

Discussion

Among adults with CLBP, both MBSR and CBT resulted in greater improvement in back pain and functional limitations at 26 and 52 weeks, as compared with UC. There were no meaningful differences in outcomes between MBSR and CBT. The effects were moderate in size, which has been typical of evidence-based treatments recommended for CLBP [4]. These benefits are remarkable given that only 51% of those randomized to MBSR and 57% of those randomized to CBT attended ≥6 of the 8 sessions.

Our findings are consistent with the conclusions of a 2011 systematic review [35] that “acceptance-based” interventions such as MBSR have beneficial effects on the physical and mental health of patients with chronic pain, comparable to those of CBT. They are only partially consistent with the only other large RCT of MBSR for CLBP [13], which found that MBSR, as compared with a time- and attention-matched health education control group, provided benefits for function at post-treatment (but not at 6-month follow-up) and for average pain at 6-month follow-up (but not post-treatment). Several differences between our trial and theirs (which was limited to adults ≥65 years and had a different comparison condition) could be responsible for differences in findings.

Although our trial lacked a condition controlling for nonspecific effects of instructor attention and group participation, CBT and MBSR have been shown to be more effective than control and active interventions for pain conditions. In addition to the trial of older adults with CLBP [14] that found MBSR to be more effective than a health education control condition, a recent systematic review of CBT for nonspecific low back pain found CBT to be more effective than guideline-based active treatments in improving pain and disability at short- and long-term follow-ups [7]. Further research is needed to identify moderators and mediators of the effects of MBSR on function and pain, evaluate benefits of MBSR beyond one year, and determine its cost-effectiveness. Research is also needed to identify reasons for session non-attendance and ways to increase attendance, and to determine the minimum number of sessions required.

Our finding of increased effectiveness of MBSR at 26–52 weeks relative to post-treatment for both primary outcomes contrasts with findings of our previous studies of acupuncture, massage, and yoga conducted in the same population as the current trial [30, 36, 37]. In those studies, treatment effects decreased between the end of treatment (8 to 12 weeks) and long-term follow-up (26 to 52 weeks). Long-lasting effects of CBT for CLBP have been reported [7, 38, 39]. This suggests that mind-body treatments such as MBSR and CBT may provide patients with long-lasting skills effective for managing pain.

There were more differences between CBT and UC than between MBSR and UC on measures of psychological distress. CBT was superior to MBSR on the depression measure at 8 weeks, but the mean difference between groups was small. Because our sample was not very distressed at baseline, further research is needed to compare MBSR to CBT in a more distressed patient population.

Limitations of this study must be acknowledged. Study participants were enrolled in a single healthcare system and generally highly educated. The generalizability of findings to other settings and populations is unknown. About 20% of participants randomized to MBSR and CBT were lost to follow-up. We attempted to correct for bias from missing data in our analyses by using imputation methods. Finally, the generalizability of our findings to CBT delivered in an individual rather than group format is unknown; CBT may be more effective when delivered individually [40]. Study strengths include a large sample with adequate statistical power to detect clinically meaningful effects, close matching of the MBSR and CBT interventions in format, and long-term follow-up.

Conclusions

Among adults with chronic low back pain, treatment with MBSR and CBT, compared with UC, resulted in greater improvement in back pain and functional limitations at 26 weeks, with no significant differences in outcomes between MBSR and CBT. These findings suggest that MBSR may be an effective treatment option for patients with chronic low back pain.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Complementary & Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AT006226. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Role of sponsor: The study funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4914381/

Contributor Information

- Daniel C. Cherkin, Group Health Research Institute; Departments of Health Services and Family Medicine, University of Washington.

- Karen J. Sherman, Group Health Research Institute; Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington.

- Benjamin H. Balderson, Group Health Research Institute, University of Washington.

- Andrea J. Cook, Group Health Research Institute; Department of Biostatistics, University of Washington.

- Melissa L. Anderson, Group Health Research Institute, University of Washington.

- Rene J. Hawkes, Group Health Research Institute, University of Washington.

- Kelly E. Hansen, Group Health Research Institute, University of Washington.

- Judith A. Turner, Departments of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington.

In conclusion, chiropractic care is recognized as an effective stress management treatment for low back pain and sciatica. Because chronic stress can cause a variety of health issues over time, improving as well as managing stress accordingly is essential towards achieving overall health and wellness. Additionally, as demonstrated in the article above comparing the effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction with cognitive-behavioral therapy and usual care for stress with associated chronic low back pain, mindfulness-based stress reduction, or MBSR, is effective as a stress management treatment. Information referenced from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The scope of our information is limited to chiropractic as well as to spinal injuries and conditions. To discuss the subject matter, please feel free to ask Dr. Jimenez or contact us at 915-850-0900 .

Curated by Dr. Alex Jimenez

Referenced from: Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Additional Topics: Back Pain

According to statistics, approximately 80% of people will experience symptoms of back pain at least once throughout their lifetimes. Back pain is a common complaint which can result due to a variety of injuries and/or conditions. Often times, the natural degeneration of the spine with age can cause back pain. Herniated discs occur when the soft, gel-like center of an intervertebral disc pushes through a tear in its surrounding, outer ring of cartilage, compressing and irritating the nerve roots. Disc herniations most commonly occur along the lower back, or lumbar spine, but they may also occur along the cervical spine, or neck. The impingement of the nerves found in the low back due to injury and/or an aggravated condition can lead to symptoms of sciatica.