Shoulder chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez examines the latest research into shoulder problems and gives practical advice on achieving balanced upper-body development.

Chronic shoulder injury is a common issue, and not only for athletes. Among the people at large, day-to-day activities such as DIY or gardening can produce chronic pain, as may resistance work at the gym, when weightlifters pile on the weight without paying attention to the demand for balanced strengthening. Adults beyond age 50 are more vulnerable to general to rotator-cuff tears, the incidence increasing with age(1).

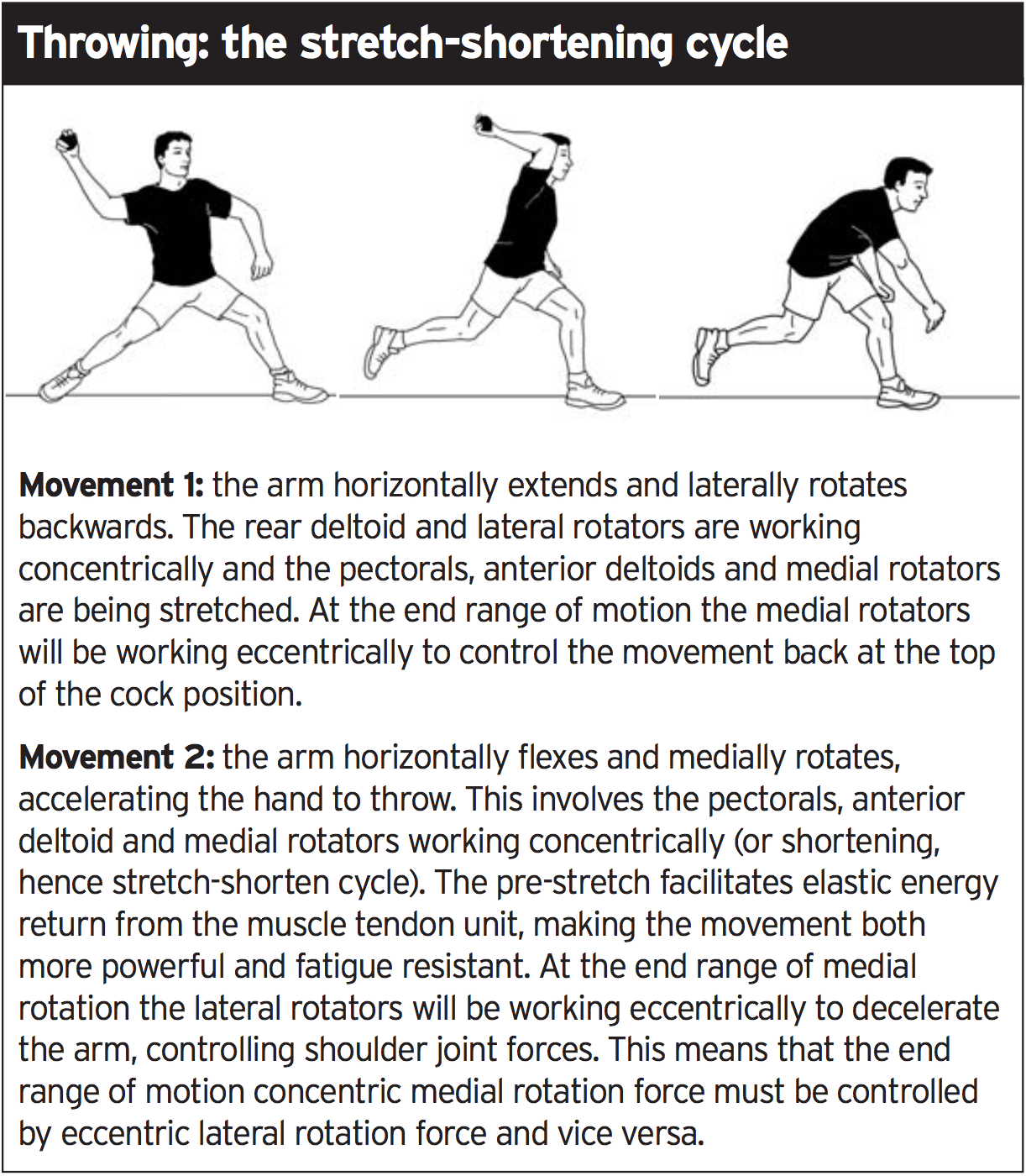

One large group, known as 'overhead athletes', are at increased risk of chronic shoulder injuries. The overhead group covers a broad array of sports such as swimming, tennis, cricket, javelin and baseball, all of which include variations on the standard throwing activity where the arm moves over the head (see below).

The throwing movement recruits a large number of muscles and unites a massive assortment of arm motion with high forces or levels at the shoulder joint. All overhead athletes often perform many repetitions of the movement, typically with the dominant arm only, as part of their sports training.

For the shoulder and arm to maneuver efficiently requires coordinated movement of the scapula and humerus, called scapulo-humeral rhythm. By way of instance, arm abduction is accompanied by some upward rotation of the scapula, allowing the deltoid muscle to maintain a good length-tension relationship throughout the whole 180 degrees of abduction.

Scapular and humeral coordination also involves the stabilizing muscles of the scapula working in concert with the rotator-cuff stabilizing muscles of the glenohumeral joint. If the scapula retains its position correctly, the rotator cuff is going to do its job more effectively. Or, to put it another way, active stability is necessary to prevent excessive stress on the shoulder joint.

Get The Balance Right

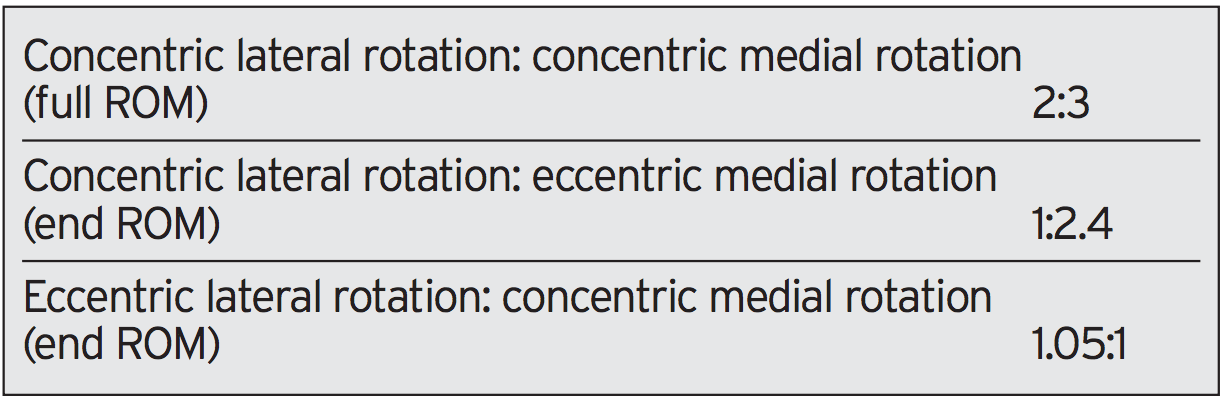

The importance of rotator-cuff muscle strength in throwing was examined by a researcher from the West Point Army Hospital at the US(2). Scoville et al looked at the strength of ordinary subjects without any shoulder injury symptoms, comparing strength ratios of the end range of lateral and medial rotation. Subjects were assessed on an isokinetic dynamometer (which measures joint strength). Full range of motion (ROM) was defined as 90 degrees of lateral rotation (forearm vertical) to 20 degrees of medial rotation (forearm 20 degrees below the horizontal). The average force produced in the last 30 degrees of each direction was assessed as end ROM.The group average strength ratios outcomes are as follows:

The results of Scoville's study suggest that ordinary adults without a shoulder problems possess adequately balanced strength for effective biomechanics of throwing. But it also shows how significant it really is for overhead athletes to keep that equilibrium of muscle strength, otherwise the lateral rotators might not have the ability to manage the more powerful lateral spinning force, compromising the shoulder joint.

Problems often arise when athletes concentrate on their training solely on the prime mover muscles, such as pectorals and deltoids, resulting in a relative weakness of the rotator-cuff and scapular stabilizer muscles. It is common practice now for overhead athletes to pay additional focus on lateral rotator strengthening. The same information will apply to all those that do resistance training: be certain to include exercises for the rotator-cuff and scapular stabilizers in order to create balanced strength in the upper body.

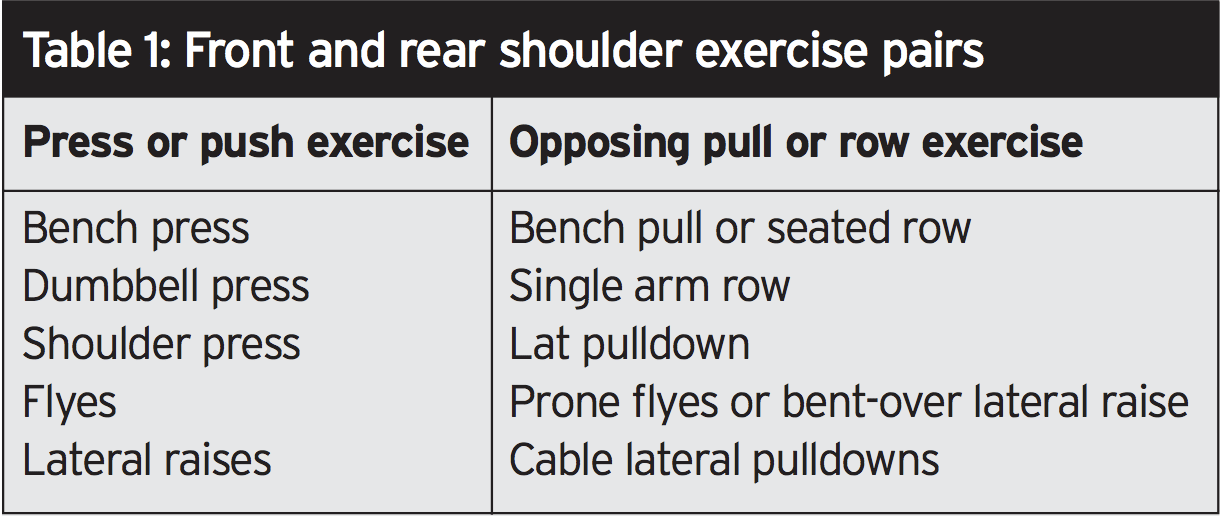

While the Scoville study analyzed rotation strength alone, we have already noted above that throwing combines spinning with flat extension and flexion movements. The rear deltoid muscles should also therefore act eccentrically to decelerate the arm throughout the end range when the pectorals and anterior deltoid are working concentrically. So strengthening applications must also look closely at back shoulder strength, including pulling and rowing movements to equilibrium pressing movements.

Here, again, gym-goers have a tendency to be most unaware of the need for balanced development, typically focusing on the 'mirror muscles' (pectorals, deltoids and biceps) and neglecting the back. The ideal program is going to be one that boosts strength in all muscle groups and also develops a balanced physique, front and back.

What Goes Wrong

Recent research from Kibler and McMullen (3) utilizes the idea of 'scapular dyskinesis': a change in the normal position or motion of the scapula during combined scapulo-humeral moves. They suggest that a wide variety of symptoms reveal exactly the same biomechanical fault, the inhibition or disorganization of activation patterns in scapular stabilizing muscles, resulting in altered scapular function.This idea is supported by research from a team from Belgium(4). Cools et al investigated the time of trapezius muscle activity during a sudden downward decreasing motion of the arm, comparing the operation of both 39 overhead athletes with shoulder impingement against the of 30 overhead athletes with no impingement. The trapezius operates on the scapula in 3 sections: the lower portion depresses, the centre portion retracts, and the upper portion raises it.

Cools measured the time that the muscles took to change on in all three parts of the trapezius and at the middle deltoid, and discovered significant differences between both groups. Those with impingement showed a delay in muscle activation of the middle and lower trapezius the muscles which are important for preserving good shoulder positioning.

Another study from Cools and his group(5) researched if 19 overhead athletes with impingement symptoms had differences in their scapular muscle power (measured by isokinetic dynamometer) and electromyographic activity on the affected and uninjured sides. They found that the injured side revealed significantly lower peak force during protraction, a significantly lower ratio of protraction to retraction force and significantly lower electromyographic activity in the lower trapezius through retraction.

Collectively these findings support the idea of scapular dyskinesis involving abnormal recruitment timing and strength of the trapezius muscle, specifically the middle and lower portions. These results indicate the importance for harm prevention of good scapular stability in the depression and retraction movements.

Research in Germany highlighted changes in flexibility at the shoulders of overhead athletes(6). Using ultrasound-based measurement, Schmidt-Wiethoff et al found that the dominant arm at a group of pro tennis players had a considerably greater range of external rotation compared to the non-dominant arm, even while their internal rotation showed a substantial deficit relative to the non-dominant arm. Furthermore, the total rotational assortment of motion of the dominant arm was significantly less than that of the non-dominant arm or of a management group. Among the control group (not included in any overhead sports), there were no important differences in flexibility between their own shoulders.

How To Protect Your Shoulders

It would appear in the study that incorrect muscle function (developed through sport-specific demands or injury) is most evident at the lower and middle trapezius and lateral rotator-cuff muscles. From a practical viewpoint this means overhead athletes and people involved with weight training need to spend time on specific strengthening exercises to encourage injury prevention and ensure balanced strength and good posture.Step 1: Equalize Front & Rear Strength

The beginning point is a balanced program for front and back shoulder muscle growth. Opposing muscle groups have to be trained equally. While exercises for the anterior shoulder and pectorals create power, to train just those muscles will unbalance the shoulder. The better approach is to plan exercise pairs that work opposing muscles (see Table 1). Coaches and therapists must check that equivalent quantities of sets from each column are written into strength programs.Step 2: Develop Good Pulling Form

It's crucial to do row or pull exercises with proper technique so as to ensure that the middle trapezius, rhomboids and lower trapezius muscles are properly recruited.As an example, the lat pulldown is a popular exercise for the upper-back and rear-shoulder muscles, involving adduction of the arm. The workout begins with the arms above the head. Throughout the pulldown motion the exerciser must focus on utilizing the lower trapezius muscles to depress the scapula while the massive latissimus dorsi muscles pull on the elbows downwards. And throughout the return motion, it's important to make the lower trapezius muscle 'keep hold' of the scapula as the arms rise with the weight.

This recruiting creates the proper scapulo-humeral rhythm. Without correct use of these lower traps, the lat pulldown is performed in a hunched shoulder position, which promotes poor mechanics.

Exactly the same coaching principle applies to rowing exercises. These involve horizontal expansion of their arm, utilizing the powerful latissimus dorsi muscles, and require concurrent scapular retraction in the middle trapezius and rhomboids. Exercisers should concentrate on retracting the scapula at the same time as the elbow is pulled straight back and maintaining the scapula retracted as the arm goes forward with the weight on the return motion. If the scapula is not stabilized the athlete will perform the practice in round-shouldered (kyphotic) posture, which again leads to bad shoulder joint mechanics.

Measure 3: Isolate The Rotator Cuff

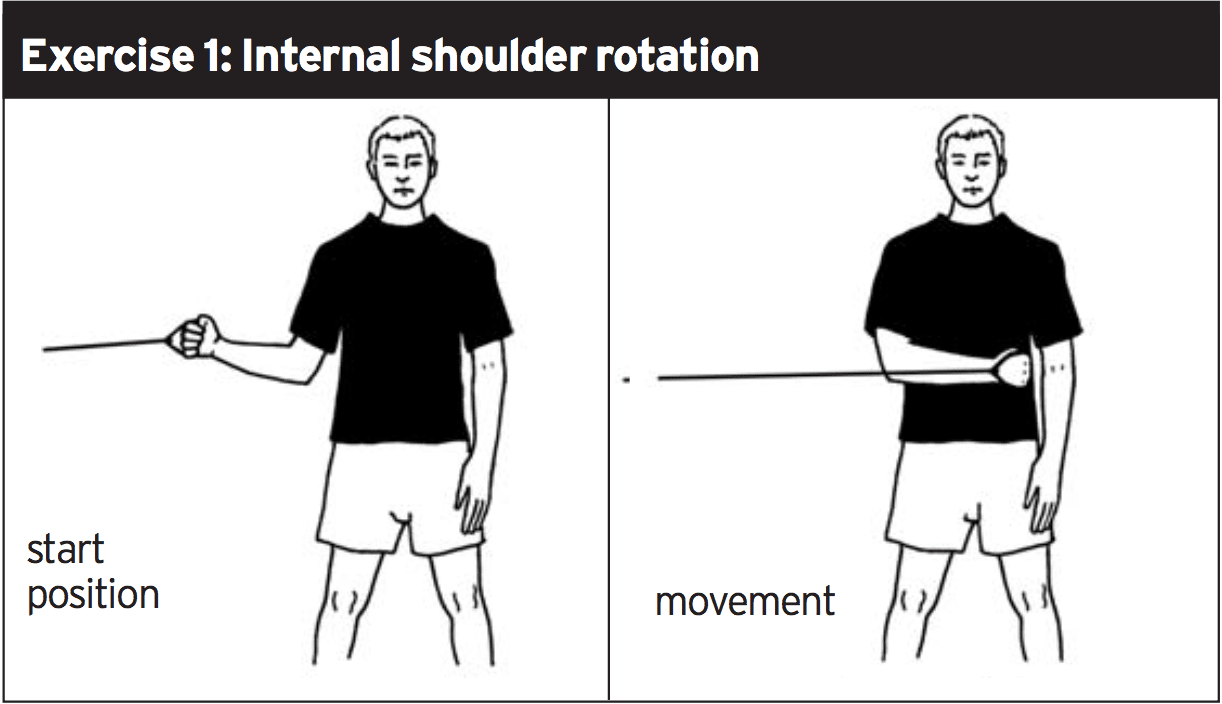

The small but essential muscles of the rotator cuff should be targeted alongside the lower traps to prevent developing weakness or dysfunction. In the following four exercises, look closely at the coaching points.Exercise 1: Internal Shoulder Rotation

Use a resistance band or a pulley cable machine for this movement.Muscles targeted

Subscapularis and pectoralis minor, the shoulder’s medial rotators.Start position

● Stand with good posture, abs in and shoulders wide.

● Grasp the handle out to the side, palm facing forward.

● Tuck your elbow firmly into your side and fix an elbow angle of 90 degrees.

Movement

● Pull arm across your body.

● Finish with the palm facing into your body.

● Keep the elbow positioned close to your side to ensure the movement targets shoulder rotation alone.

● Hold upper body still, to prevent other muscles assisting the shoulder. Only your arm moves.

● Return to the start position slowly, under control, and repeat.

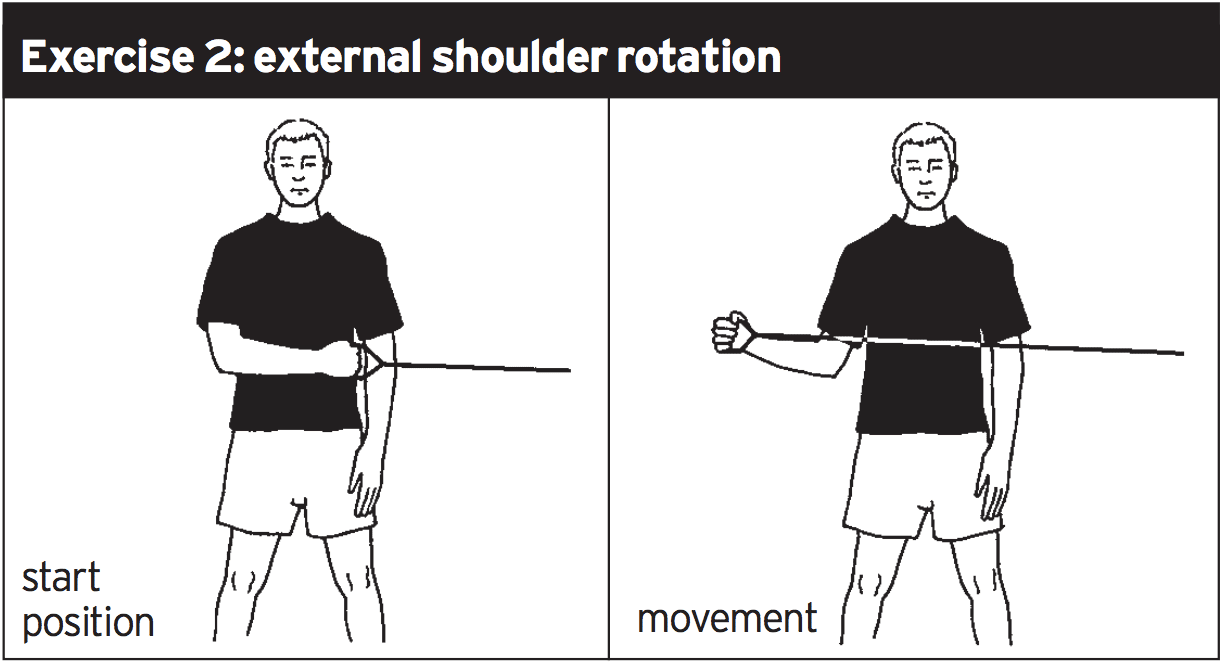

Exercise 2: External Shoulder Rotation

Use a resistance band or pulley machine.Infraspinatus and teres minor, the shoulder’s external rotators

Start position

● Stand with good posture, abs in and shoulders wide.

● Grasp the handle with your forearm across your body, palm facing into your body.

● Hold your elbow close to your side and fix an elbow angle of 90 degrees.

Movement

● Pull the arm out and away from your body.

● Finish with the palm facing forward.

● Keep the elbow positioned close to your side to ensure the movement targets shoulder rotation alone.

● Hold upper body still, to prevent other muscles assisted the shoulder. Only your arm moves.

● Return to the start position slowly, under control, and repeat.

Exercise 3: Side Lying Raise

Supraspinatus (top of the rotator cuff), assisted by the deltoid and infraspinatus. This exercise is particularly effective at recruiting rotator-cuff muscles while avoiding putting the shoulder joint through a stressful range of motion. It is therefore beneficial for those with shoulder injury.

Start position

● Lie on your side with your body straight.

● Place top arm straight so your hand lies by your hips, holding a dumbbell.

● Use your scapular muscles to pull your top shoulder into a wide position. Avoid hunched or rounded top shoulder.

Movement

● Lift the dumbbell straight up until your arm makes a 45 degree angle.

● Ensure your body does not roll or sway, only your arm moves.

● Lower the arm slowly, under control, and repeat.

Exercise 4: Human Arrow

Muscles targetedLower trapezius, focusing on scapular depression. This movement can take a little time to learn, so don’t expect clients to get it first time.

Start position

● Lie on your front with your arms by your sides.

● Have your palms facing up and fingers pointing towards your feet.

● Eyes look down into the floor, nose just off the ground.

● Do not lift your head, so your neck remains relaxed.

● Engage your abdominals and pelvic floor to keep your lumbar spine in place.

● Let your shoulders fall forward and rounded to the floor. Upper back starts relaxed.

Movement

● Pull your shoulder blades back and down so that your fingers slide down your side towards your feet. Feel that you are extending your arms down.

● Your upper back will extend slightly and all your muscles around your scapula will feel strong. You will feel your shoulder blades pull downwards into your back if you engage the lower traps correctly.

● Do not extend your lumbar spine and lift up off the floor. The low back should remain flat as the exercise is designed to isolate the scapular muscles. It is not a dorsal raise.

● Hold the position for 10 seconds and relax.

● Repeat 10 times.

References:

1. Milgrom C, Schaffler M, Gilbert S, van Holsbeeck M, Rotator cuff changes in asymptomatic adults. The effect of age, hand dominance and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995 Mar; 77(2):296-8

2. Scoville CR, Arciero RA, Taylor DC, Stoneman PD, End range eccentric antagonist/concentric agonist strength ratios: a new perspective in shoulder strength assessment. Journal of Orthopaedic Sports and Physical Therapy 25(3), 1997

3. Kibler WB, McMullen J, Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003, 11(2)

4. Cools et al. Scapular muscle recruitment patterns: trapezius muscle latency with and without impingement symptoms. Am J Sports Med. 2003, 31(4)

5. Cools et al. Evaluation of isokinetic force production and associated muscle activity in the scapular rotators during a

protraction-retraction movement in overhead athletes with impingement symptoms. Br J Sports Med. 2004 38(1)

6. Schmidt-Wiethoff et al, Shoulder Rotation Characteristics in Professional Tennis Players. Int J Sports Med. 2004 Feb;25(2)