It was once believed that inflammation caused impairments such as plantar fasciitis, tendonitis and iliotibial band syndrome -- but new research shows that may not be the case. Injury specialist Dr. Alexander Jimenez examines the data.

The body was made to move; however, moving too far or too often in a repetitive way can overexert tissues. New research is now calling into question the concept that inflammation causes these conditions -- and this may affect our understanding and treatment to what had been considered tendonitis and fasciitis.

Connective Tissue

Ligaments, tendons, ligaments and fascia hold the bony skeleton together. Quite simply, the muscles move the manhood; the tendons connect muscles to bones; the fascia encases the musculotendinous unit, and sometimes become a functional part of the unit, as is true for the iliotibial band and the gluteus maximus and tensor fasciae latae muscles; and the ligaments connect bones to bones.An athlete might have the occasional ligament strain or inherent ligament laxity, but the tissue itself typically either does its job or doesn't. Current thought on the causes and therapy of the chronic injury of those tissues may change the way you exude your endurance athletes.

Fascinating Fascia

Fascia exists as an uninterrupted matrix of collagen that extends throughout the entire body, forming a web of covering and connection between all organs and muscles. Therefore, it is nearly impossible to isolate and name a region of the continuum in any other way than its nearest anatomical structure. It's three- dimensional and contains freedom in all three planes of motion(1).While one continuous membrane, fascia has distinct inherent characteristics based on its location and function. Fascia that exists among muscles aids to transmit forces in addition to absorb strain.Studiesinlive specimens with ultrasound reveal that fascia is viscoelastic -- using both viscous and elastic characteristics when deformed -- and is therefore able to slip independently of the contraction of the muscle that it surrounds(1).

Fascia is composed of at least nine of the 28 types of known collagen. Collagen gives construction, durability and strength to the tissue. The extracellular matrix of fascia includes the elastic fibers which provide flexibility. Myofibroblasts are also present in fascia, leading, hypothetically, to its contractility, tension, and equilibrium(1). Fascia has a characteristic fiber arrangement parallel to the common force vectors to which it can be exposed.

Tale Of The Tendon

Mechanism Of Injury

Tendon and fascial injuries both result from overloading. Acute injuries are usually considered as resulting after a one-time incident of intense loading. A chronic injury, subsequently, is considered something that occurs after repeated excessive strain. However, some theories assert that acute accidents occur due to chronic underlying micro-stress into the tissue(two). In any case, nearly 50% of sports injuries reported from the USA are the result of overuse(3).Traditionally, both tendon and fascial injuries were considered inflammatory processes and were consequently named tendonitis and fasciitis. As more is understood concerning the mechanics of both injury and healing, this nomenclature is now called into question. Tendinopathy is the catch-all phrase that covers any abnormal state of the tendon. Tendonitis refers to some true inflammatory reaction due to bleeding within the gut as a result of an intense event. Tendinosis is the condition of tendon degeneration that develops over time in the lack of a true inflammatory response. It's considered a state of overuse, however, though, can coexist with an inflammatory process from the paratenon. Actually, degeneration along various points on this spectrum can be found all within exactly the same tendon.

A barbell with tendinosis differs histologically from tissue that is healthy. The collagen alignment in tendinosis is no more parallel and the distance between the collagen bundles increases. The tenocytes become much more notable. The quantity of type-III collagen additionally increases when compared to type-I, which generally composes 90 percent of the collagen in healthy tendon(3). Despite an increase in fibroblasts, there are no inflammatory cells present in the extra-cellular matrix. There is an infiltration of blood vessels and nerves, which is referred to as neovascularisation. These microscopic findings are indicative of a fix process gone awry, resulting in further tendon degeneration.

It appears that in response to excessive strain or overuse, the tendon attempts to initiate a healing process that fails to regenerate and really further degenerates the tissue. Some theorize that inflammation occurs initially, but that the repetitive nature of the mechanical stress results in interruption of the normal recovery procedure. When inflammation occurs within a healthy tendon the tenocytes turn into myofibroblasts. The myofibroblasts then normally undergo cell death; however, in tendinosis, the repeated stress may interrupt this process, causing a proliferation of myofibroblasts which cause fibrosis of the tissue.

Hypoxia can interrupt the homeostasis of this extra-cellular matrix, which causes an increase in blood vessels and corresponding nerve pathways. The gain in sensory nerve pathways at the neovascularisation process is thought to be the cause of greater pain in tendonosis(3). The pain of this neo- vascularisation may cause an athlete to insufficiently load the tendon to activate the normal tenocyte reaction to strain, thus further inhibiting healing. The lack of repair contributes to microscopic tears which can finally cause tendon rupture.

Treatment

Fasciitis and tendinopathy are often considered difficult conditions to deal with because of the poor outcomes when using conventional inflammation combating strategies. Understanding that an athlete's condition might not really be an inflammatory process is important when choosing the proper healing modalities. The exact same is true with the usage of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs). While maybe mediating the pain, they don't improve the condition. Masking the pain might cause additional harm as the athlete continues to execute the offending action. Treatment with NSAIDs must be undertaken acknowledging the lack of evidence of efficiency, in addition to the risks related to such drugs, most especially gastro-intestinal upset.Some modalities are found to be useful in the management of tendinosis and fascial injuries. Intense friction massage, using a tool or merely manually, is often used to evoke changes in the tissue through a physical manipulation that triggers a recovery reaction. True randomized controlled studies are lean for its treatment of tendinosis, and lacking altogether about fasciitis. However, case studies show great results with friction massage when utilized as an adjunct to other therapeutic methods(4).

The use of low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is controversial at best. An overview of six distinct systemic literature reviews on the use of LLLT with tendinopathy came to the conclusion that there isn't enough conclusive evidence to advocate its use in the therapy of tendinopathy(3). The same holds true in the case of ultrasound treatment. While thought to trigger recovery through adrenal effects, ultrasound hasn't been found to be beneficial. The accession of drugs through using ultrasound (phonophoresis) or electric impulses (iontophoresis) conveys nearly the very same effects as LLLT and ultrasound alone. Studies conflict as to the effectiveness of all of these modalities.

What's New?

New on the horizon is the use of extra- corporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) for the treatment of tendinosis and fascial injuries. Shockwaves are delivered via electromagnetic, electro hydraulic, or piezoelectric sources. The tech for ESWT is a derivative of the lithotripsy used as a treatment for kidney stones. The waves are significantly more focused and intense than those by an ultrasound device. Initial studies of the use of ESWT in the treatment of resistant tendinopathy show excellent results, especially with athletes(3). The same is true from the preliminary research treating plantar fasciitis with ESWT. Patients report better outcomes in pain relief and operate with ESWT than with operation or corticosteroid injections(5). But, because of the need for more large and long-term studies on its efficacy, it is not advocated as a first line treatment.

A Shot In The Arm, Leg, Or Ankle...

A well known method of handling inflammation, corticosteroid shots have long been used with limited success in the management of tendinopathies and fasciitis. The reason for the limited success must now be nicely apparent. Theoretically, tendon degeneration may result in inflammation of the paratenon, which leads to the pain of the injury. Injection adjoining to the injury can help with the inflammation there, but the root cause of degeneration is not assisted whatsoever. If shots are undertaken, they need to be achieved with the assistance of fluoroscopic guidance to assure that the delivery of this steroid is adjacent to the tendon, not inside.Despite a dearth of evidence to support its use, corticosteroids are still a first line treatment for fasciitis, particularly plantar fasciitis. A British Medical Journal Clinical Evidence report even went so far as to say that steroid injections might be injurious to the plantar fascia through the years(6). This lack of evidence prompted researchers in the section of rheumatology in Musgrave Park Hospital in Belfast to compare the use of ultrasound guided corticosteroid injection to that of non-guided injection and placebo injection in the treatment of plantar fasciitis(7). Results revealed considerable improvement utilizing corticosteroid as opposed to placebo at six and twelve months, although no gap between guided and unguided injection was shown. But, glaringly absent in this research is a description of concurrent or previous treatments undertaken by the participants, or restrictions from the same. Additionally, knowing that, oftentimes, plantar fasciitis is self-limiting, together with progress generally in three to six months, more studies are required to encourage the regular use of steroid injections in treating fasciitis.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is just another process of injection therapy that's gaining in popularity. A concentration of platelets is drawn from an individual's own blood and re-injected at the site of injury. The theory is that the lab-activated platelets will activate enhanced collagen production and promote healing. There aren't any dependable, controlled studies now that reveal PRP to be greater compared to other injectables or physical therapy alone, in treating tendinopathy and fasciitis(3,5). Better-regulated research are required before clinical evidence as to the efficacy of the injection-based treatment approach can be revealed.

First-Line Treatment & Last-Ditch Effort

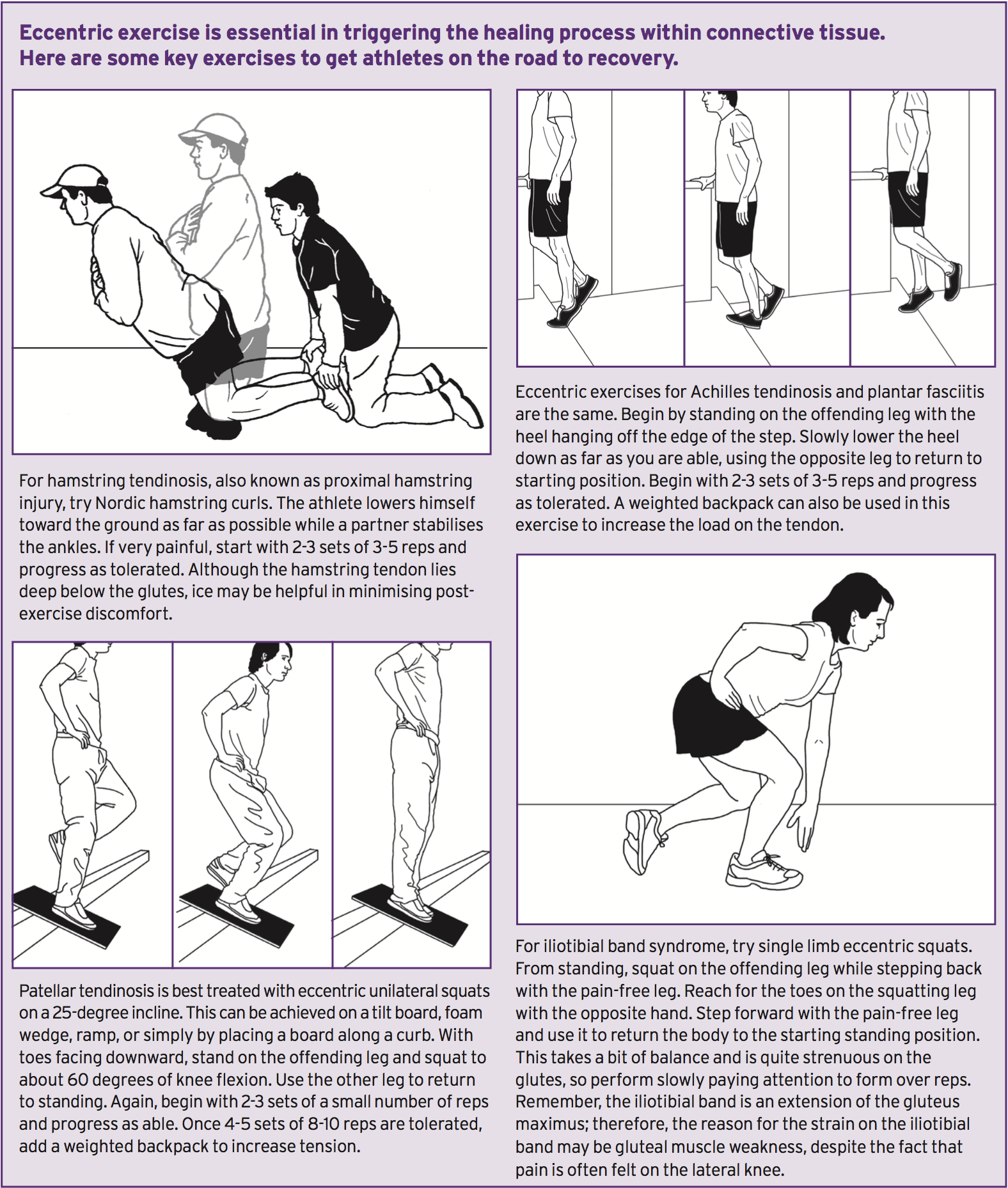

Overwhelming evidence exists to support the use of eccentric exercise in the treatment of tendinopathy(2,3). Loading the injured tendon appropriately appears to be crucial in preventing the degenerative cascade and initiating proper recovery. The specific mechanism through which eccentric exercise can reorganize the tendon structure isn't well understood; however, it's thought to nourish the tenocytes and reunite the extracellular matrix into homeostasis.Frustrated Yet?

Indeed, that is how many coaches, therapists and athletes believe about the nagging injury that, despite everyone's best efforts, just won't go away. The new comprehension of connective tissue structure and function challenges how typical overuse injuries are treated. No longer considered inflammatory in nature, unless very obviously acute, tendon and fascial injuries call for a novel approach to treatment. In order to bring about healing, a change has to be triggered in the harmful physiological cascade that leads to tissue degeneration. Eccentric exercise, ESWT, transdermal NO, and possibly deep friction massage, are all demonstrating the best results thus far in causing tendon healing and halting degeneration. The specific mechanism by which these treatments work isn't well known. Other remedies methods ought to be inspected, and possibly discarded, until study reveals their efficacy.Truly halting the progression of an overuse connective tissue harm needs the expert eye of a physiotherapist, trainer, and coach to evaluate musculoskeletal status and motion routines, technique, training schedule, and gear. Very often, there's an offending component that's been overlooked. Once corrected, the connective tissue strain will be eliminated and curative intervention will have a chance to get the job done. In overuse injuries, a more comprehensive approach has to be taken to avoid additional tissue degeneration and injury.

References

1. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56(3):179-91

2. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1620-8

3. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2013;40:453-73

4. J Sport Rehabil. 2012 Nov;21(4):343-53

5. J Fam Pract. 2013 Sep;62(9):466-71

6. Clin Evid 2008. 2008:1111

7. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:996-1002