Legend has it that every year the body department staff at one of the United States' top universities lay down bets on how long it will take before the new medical students discover the "freshman's nervel" when the time comes to dissect the lower limbs of cadavers. Science based chiropractor Dr. Alexander Jimenez takes a look.

The clinical tutors take great joy in hearing the enthusiastic exultations of medical students as they pare back the gastrocnemius muscle of the calf to be presented with what appears a nerve- like arrangement. "Wow, look at this, I just discovered the tibial nerve!"

After allowing time for backslapping and high fives one of the students, the tutor slides over to the dissection table to point out that what they have just found is not actually the tibial nerve but the tendon of the plantaris muscle. The slender plantaris is the topic of the subsequent case study, outlining the rather debilitating injury known as "plantaris tendon rupture".

Mr B's Bumpy Ride

Mr B, a 45-year-old recreational cyclist, introduced to physiotherapy one week after he felt his calf tear while skiing. He was a long-term Warfarin user ever since, a few years before, he had had a surgical C5/6 combination that had resulted in some horrible blood clots. His last clot had been more than 12 months previously.

Mr B described the ski hitting the top of a mogul and forcefully dorsiflexing his foot while his knee was extended, also forcefully. He felt immediate calf pain and was not able to bear weight on the leg.

Upon evaluation a week after, Mr B had a tight swollen calf and was not able to walk without a limp. He could not walk down stairs, push off in walk or twist on a fixed foot. Stretching the gastrocnemius was debilitating.

We immediately suspected a garden variety muscle strain of the gastrocnemius and proceeded to treat him with mild soft-tissue flush massage, direct trigger- point therapy, heat and motion therapy, compression and mild isometric calf exercises, which we progressed to single-leg calf increases as pain allowed over a number of days.

After nine days, Mr B has been walking pain- free and managed to perform 3 x 15 one-leg calf increases without pain. He had been discharged from physio with directions to continue calf raises for four weeks, and also to progress his return to biking from wind trainer to flat streets to hills over the same period of time.

Twelve days after we had discharged him, Mr B had been gardening and, while on a slope, his foot slipped. He was forced into rapid dorsiflexion and knee extension again. He felt immediate pain and has been unable to weight-bear. Back at the practice, he revealed significant calf swelling and tenderness at the posterior knee. Concerned that we were looking at something more menacing than a simple calf strain, we delivered him for a diagnostic ultrasound.

The ultrasound clarified the plantaris tendon as being "blind ending" from the calf, suggestive of plantaris rupture. There was a massive hematoma in the gastroc/soleus fascia. No extra gastrocnemius or soleal tear was discovered.

We explained to Mr B this rather unexpected pathology. He had been handled the same way as previously, but we focused on lots of friction massage to his torn plantaris tendon and also a far slower and more conservative return to rehabilitation and cycling; we also threw in certain single-leg proprioception exercises for good measure.

He returned to cycling three months later with no further problems.

Anatomy

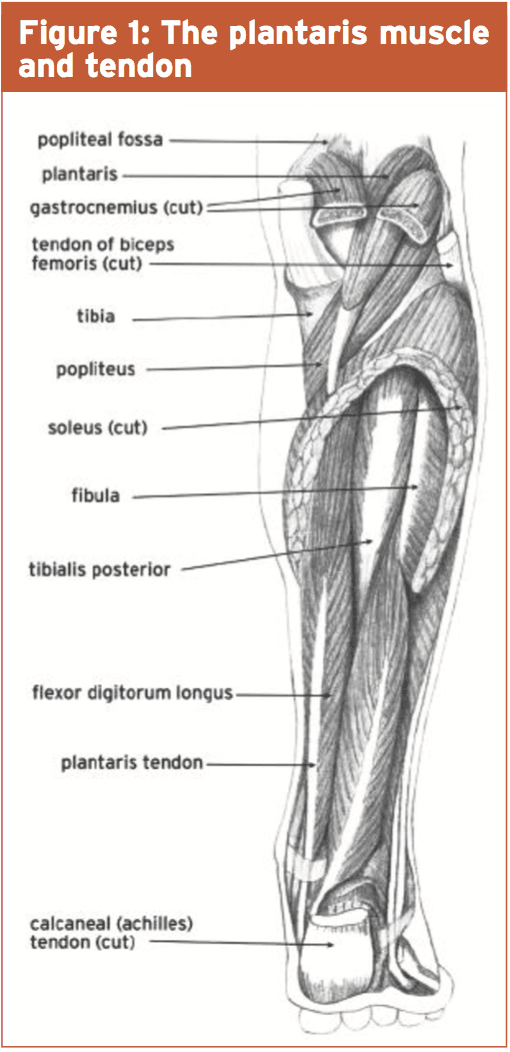

Along with the soleus and gastrocnemius, the plantaris forms the “triceps surae” muscle of the calf (see Figure 1, below). It originates on the lateral femur as a rather small, pencil-like muscle. It is 7 to 13cm long and runs downwards and medially. It then forms a thin, long tendon that courses medially to extend all the way down the medial calf and medial side of the Achilles tendon, inserting on to the calcaneus (main heel bone). It runs between the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles. This long, slender tendon is often mistaken for a nerve – hence the term “freshman’s nerve”. It is absent in 7 to 10% of the population(1).

Moore and Dalley suggest, however, that the muscle has a high percentage of muscle spindles (2): glands in the muscle that are highly sensitive to extend. It therefore seems possible to me that perhaps this muscle building functions just a proprioceptive role, a hypothesis shared with Menton in his very interesting argument about plantaris being a "sensory muscle (3)".

This point has merit once we consider we're the only animals that stand upright on two feet. In standing with the knees extended, this muscle will always be shooting and fine-tuning our standing posture, helping us to maintain equilibrium.

However when injured it may result in ongoing pain and disability, and potentially thwart the development of a serious athlete hoping to return to a running-type sport.

Injury

Rupture of the plantaris muscle/tendon has often been referred to as "tennis leg", because of its tendency to rip in middle- aged tennis players. In fact, they frequently describe the sensation as one of being struck in the calf with a tennis ball. It is an accident nearly entirely continued by the athlete over 40, being nearly unheard of in younger athletes. But a case study does exist emphasizing this injury in a professional footballer (4). Injury to this muscle/tendon must always be guessed in athletes presenting with severe medial calf pain, irrespective of age.The plantaris tendon can rupture when vigorously contracted, especially if the ankle is dorsiflexed and the knee extended. Imagine a tennis player lunging to get a ground stroke and needing to push off forcefully while down low to the floor.

Although the muscle is quite small and the tendon very thin, the pain can be very intense and is felt at the medial gastrocnemius; immediate swelling and haematoma cause this area. It's easy to mistake a plantaris tendon rupture for a gastrocnemius muscle rupture.

On the positive side, plantaris tendon ruptures usually recover much faster than gastrocnemius tears. Because of this, MRI or ultrasound imaging may be desired in order to determine the damaged structure. This will enable the clinician to make a better judgement about how long that the rehabilitation is likely to take and how the prognosis appears longer term.

What's more, ruptures of the myotendinous junction of the plantaris are often thought to be more severe than simple ruptures or tears of the tendon proper. The pain in this instance will be much more severe and the muscle will retract upwards into the popliteal space, often between the popliteus tendon and the lateral gastroc head. The resultant hematoma is frequently also more severe and functionally more debilitating. Ruptures of the plantaris muscle are often seen in conjunction with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures (1). This also suggests that the injury mechanism for a plantaris muscle equilibrium can actually be like the mechanism for ACL rupture.

Treatment

There is a lack of scientific evidence on conservative versus surgical procedures in plantaris muscle or tendon rupture. Much of the philosophical literature implies that the injury should be handled along the very same lines as another muscle injury, bearing in mind that its small size must allow the muscle to fix quickly.Ice treatment when maintaining the muscle elongated helps to regenerate the muscular tissue faster and to a more functional and aligned matrix. This can be done by icing the calf with a straight knee; the ankle is slowly dorsiflexed and plantar flexed. The muscle should be kept compressed when not iced.

Active release techniques, soft tissue massage, trigger point therapy etc can be used to help enhance calf muscle tone and speed the elimination of the hematoma.

Progressive strengthening can then start as pain permits. This can start as a simple isometric calf hold exercise on a step and then later progress to complete eccentric calf loading as pain and function improve.

References

1. Helms et al (1995) Plantaris Muscle Injury: Evaluation with MRI imaging. Radiology. 195 (1) p. 201-203

2. Moore KL, Dalley AF (2006, Philadelphia) Clinically Orientated Anatomy. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins

3. Menton DN (2000) The Plantaris and the Question of Vestigial Muscles in Man, Technical Journal 14 (2): p. 50–53

4. Bradshaw et al (2005) Traumatic Achilles Paratendinopathy Complicated By Plantaris Tendon Rupture And Subsequent Post-surgical Complications. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise: May 2005 37 (5) p. S281