Chiropractor, in part 1, Dr. Alexander Jimenez outlines the relevant anatomy and biomechanics of the ACJ, the way they are hurt to clinically assess injury and the radiological requirements in determining the extent of injury.

Introduction

Injuries to the acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) are recreational pursuits like cycling and a injury in the athlete. It’s a frequent complaint in contact sport athletes like rugby, AFL, NFL and combat sports like MMA and judo. In actuality, Headey et al (2005) show that in elite level rugby union in the United Kingdom, ACJ injuries account for 32% of shoulder injuries, being the most frequent structure to be hurt playing Rugby Union.These injuries are managed Remains controversial. Low grade ACJ sprains are managed conservatively the ACJ separations could be managed surgically or non-surgically. Bosworth at 1941 offered the surgical intervention to ACJ dislocations. Surgical methods are available to repair a ACJ today.

Relevant Anatomy & Biomechanics

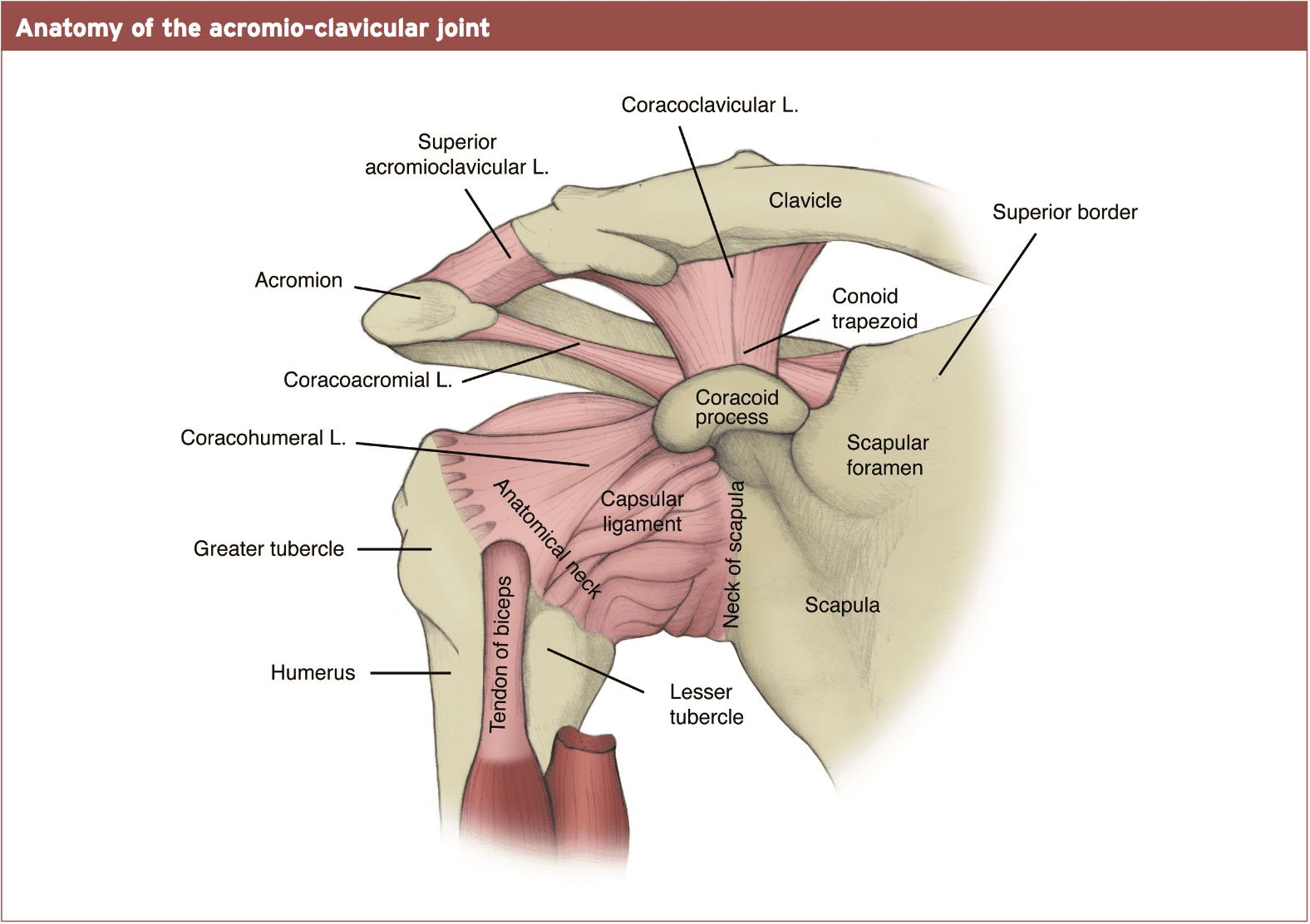

The ACJ is a diarthrodial joint with four planes of motion, anterio-posterior (forwards and backwards) and supero- inferior (down and up). It’s also able to spin on its axis. A capsule surrounds the joint and has an synovium making a synovial joint. Both clavicular and acromial bones are covered with a cartilage (hyaline in late teens and early twenties that matures into fibrocartilage from the 20s).

The ACJ also has an intervening meniscoid disc between the two bones. The specific use of the meniscoid disc is poorly known and the disc is not as well defined since the menisoid disc that’s placed within the sternoclavicular joint (SCJ). This may explain why the disk degenerates with age. By age 40 it might be non-existent (Peterssen 1983). Because of the small nature of the disc along with the large compressive forces struck in the joint due to muscular contraction of the powerful shoulder muscles like the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi this disk is thought to be prone to premature breakdown along with the distal end of the clavicle. Both the disc and distal clavicle are prone to compressive failure, evidenced by the high rate of osteolysis in the distal clavicle, especially in athletes who impose substantial drives on the joint such as weightlifters (Richards 1993).

The ACJ is supported by four AC ligaments — inferior, superior, anterior and posterior. Excess movement is prevented by these ACJ ligaments. What’s more, ligaments combine the coracoid process to the clavicle (the coracoacromial ligaments — CC ligaments) and these would be the trapezoid and conoid ligaments. These ligaments provide superoinferior support (up and down) as well as anterior translation service.

After the acromion and the separate clavicle (collapse on the shoulder) the ACJ ligaments would be the first ligaments to extend and withstand force (in particular the exceptional ACJ ligaments), followed then by the conoid ligament and trapezoid ligament. Therefore, injuries to just the AC ligaments may be considered a stable injury whereas trauma to the conoid / trapezoid ligaments will result in there being part of the CC ligament complex in addition to disruption of the ACJ.

Back in 1986, Fukuda et al performed a research play at ACJ stability. What they found could be summarized below:

1. The AC ligament acts as a main restraint to anterior clavicle displacement and rectal axial rotation;

2. The conoid ligament constrains anterior and superior rotation as well as superior and anterior displacement of the clavicle.

Furthermore, Rockwood (1998) says that the AC fibres blend with the upper trapezius and deltoid’s fibres which attach to the aspect of the clavicle and acromian, and consequently he argues these muscles may be significant in providing the ACJ with active support.

Injuries To The ACJ

Accidents to the ACJ are far more common In men in their twenties, highlighting behavior as a element in ACJ injury. Young men are involved in pastimes and sports that will lead to a traumatic ACJ injury. Sports such as football, rugby, motorcross riding, mountain bike riding and combat fighting (judo, MMA, ju jitsu) are sports where there is a potential for traumatic ACJ injury.The most frequent mechanisms of Injury are direct falls onto the shoulder and the clavicle separates in the attachment that is acromial. This sometimes happens in contact scenarios in the football sports or falls off a bicycle.

After the acromian contacts the floor, a downward displacement of the clavicle is primarily resisted through an interlocking of the sternoclavicular ligaments (Bearn 1967). The clavicle remains in its normal position, along with the scapula and shoulder girdle are driven. A downward force being applied to the superior aspect of the acromion’s outcome is give-way of the CC and AC ligaments or clavicle fracture. There may be an anteroposterior direction to the force. Tears of the deltoid and trapezius muscle attachments occur from ruptures of the CC ligament, as well as the clavicle if the pressure proceeds. With pressure, the epidermis can also be interrupted. From the rare type VI injury to the AC joint, a mechanism of harm is responsible. A direct force onto the surface of the distal clavicle has been described. The clavicle is pushed where it lodges under the coracoid or the acromion.

A fall onto an outstretched Arm may force the humeral head to push against the acromian leading to an ACJ separation. This is called an indirect injury. These type of injuries impact the AC ligaments and the CC ligaments remain intact.

Clinical Assessment

Usually the mechanism of injury is obvious ACJ pain after a direct fall onto the shoulder’s point. Anxiety highlighting a grade ACJ injury and gross swelling could be evident in addition to a clear step will be felt within the ACJ.Most measures like range of movement (especially horizontal adduction) will be pain-limited, and also the capability to create isometric rotator cuff strength will also be pain-limited. In low regular injuries, frequently the athlete is able to reach of motion; nonetheless tier will be pain-limited.

Radiography

A range of exposures are required to properly visualize the ACJ and the structures. This is best described under the following points:1. Reduce the penetration to A half of the commonly employed for a shoulder x-ray.

2. Zanca view is the best for visualizing the ACJ. This is done by leaning the x-ray beam 10-15° cephalad and imaging equally ACJ on the same cassette to compare the coraco-clavicular distance (CC distance).

3. Axillary view is required for Type IV Injuries in which the clavicle has been posteriorly displaced.

4. A Strykner notch view is the opinion for imagining process cracks.

5. Stress views using weights connected to the wrist (rather than holding in the hands) is used to exacerbate the ACJ separation.

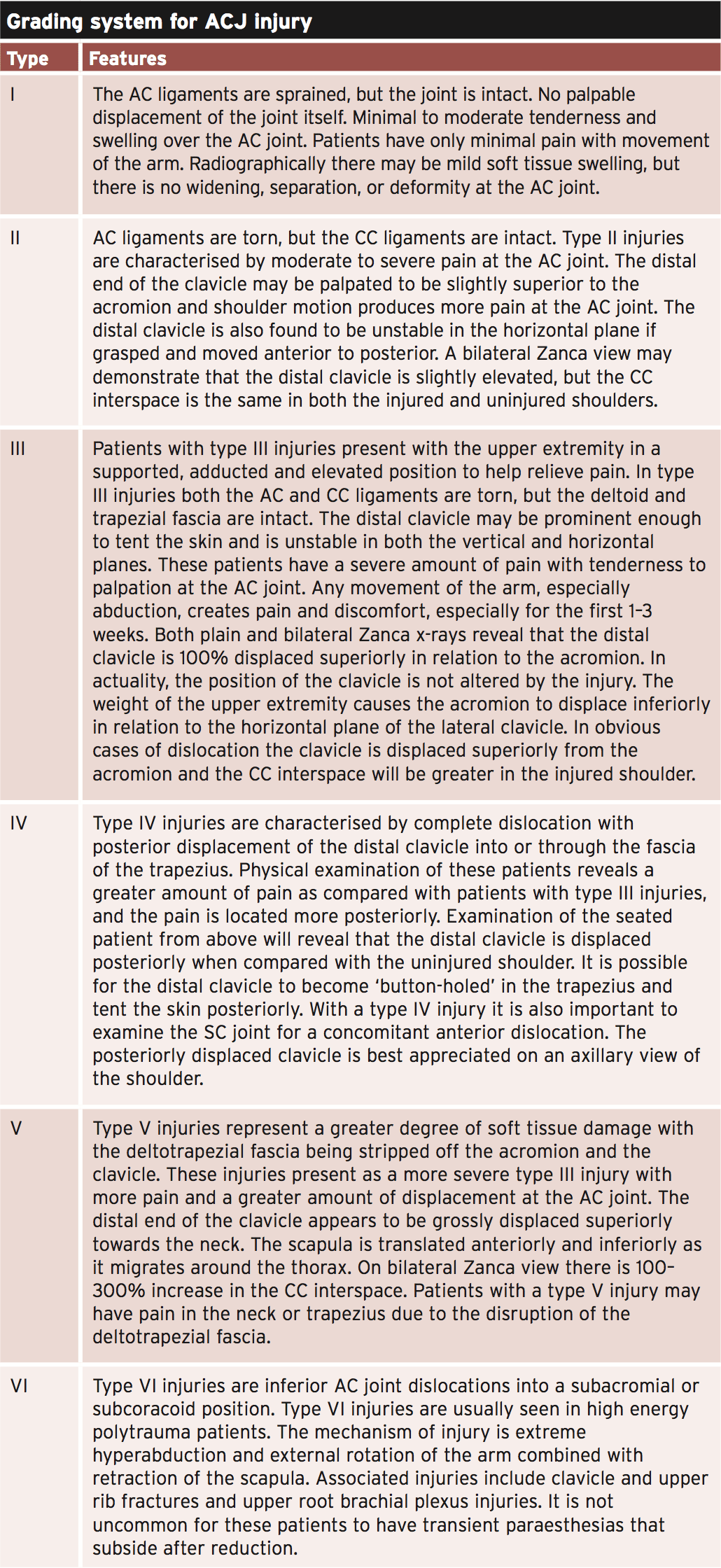

Tossy et al (1968) and Rockwood (1998) Provide the most comprehensive grading system for ACJ harm, and all these are typed from Form I-VI (see Table).

Management Of AC Injuries

Normally, Type I ACJ separations are minor accidents and are treated. This will involve a brief period of immobilization to reduce the strain on the AC joint this is not common across all sport. Standard ice is used to your first 48 to 72 hours. As with most severe soft tissue injuries, non-steroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are usually avoided for the first 3-4 days due the capacity for delayed healing of collagen structures (Warden 2005). Immediate tender and isometric range-of-motion exercises are encouraged. There is a structured strengthening program initiated whenever the individual’s symptoms begin to resolve.Gross power movements (gym-based) can be gradually improved, typically in the following order:

1. Horizontal pulling movements (seated Row, prone fly, bent over row);

2. Vertical pulling — elbows facing Shoulder (near clasp pull-downs, hammer grip chin ups, direct arm pull-downs);

3. Horizontal pushing (bench press, dumbbell bench press);

4. Vertical pushing (shoulder press movements);

5. Diagonal PNF patterns.

Type II injuries usually involve more soft tissue injury. Although the time frame is as a result of the trauma treatment for type II injuries is exactly the same as for type I injuries. A period of immobilization will be needed. A sling is generally used for 1 to 2 weeks. The patient is informed that a cosmetic deformity may be present after the injury is healed.

The time period for return to sport is varied based on severity of initial injury, type of sport played, associated previous shoulder injuries. Simple type 1 injuries may be back within 7-10 days, more type II accidents might take up to come back to full function to sport. The attention in part two of the guide will be on the rehabilitation after surgical fixation of the ACJ in kind III-VI injuries.

Conclusion

ACJ injuries are common injuries in the contact sport athlete and in recreational pursuits the victim falls upon the point of the shoulder. A collection of AC and CC ligaments which may fail leading surrounds the ACJ.The benign kind I and II injuries may be managed the type III injuries type the ‘hard to decide’ category whereas type IV, V and VI need intervention.

Part 2 of the masterclass will outline in detail the surgical options available to reconstruct the and a kind IV-VI injury typical post-operative rehabilitation.