Chiropractor Alexander Jimenez takes you through the second part of rehabilitation masterclass for the surgically repaired acromioclavicular joint (ACJ).

Surgery For ACJ Injuries

Type III injuries and type II injuries in the high-level throwing athlete is the start of the spectrum for the decision. This is usually based on a case–by-case basis, and the standards for surgery versus conservative direction may be based on:1. Injury to Left the joint a small degenerative (new on older injury).

2. For individuals in high risk sports (contact Game, combat sports, motocross) where the danger of re-injury may be quite high, the initial preference would be to care for the ACJ conservatively. This might push on the surgeon to think about a procedure if the ACJ is re-injured.

3. In throwing sports dominant arm, early surgery clicking and popping on account of the biomechanical loads in the ACJ or may be preferred to prevent any sensations of ACJ instability.

4. Arm dominance. Injuries to the ACJ On the side might be a factor in early operation.

5. Amount of uncertainty. Instability at the Direction tend to do poorly with direction compared with the up-down kind instabilities.

The decision to Handle Type III injuries surgically versus non-surgically still remains controversial. Some researchers have found that the results following surgical versus non-surgical AJC injuries is very similar (Calvo et al 2006).

If the decision is to postpone surgery on a Type II and III ACJ injury, then the usual time period is three months of conservative rehab. If the athlete complains of pain, sensations of instability or an inability to perform game at preceding levels of functionoperation is subsequently considered.

The more serious kind IV, V and VI will always need operation.

Kinds of Surgery

There are four Kinds of procedures which have been described for remedy of ACJ injuries. These include:(1) Primary repair of the AC joint With rods, screws, plates, tension band wiring or pins.

This procedure involves an open repair of the ACJ using a host of options that are fixating. These may be done with or without CC ligament reconstruction. A comparative study performed by Sugathan and Dodenhoff (2012) found the tension band wiring, although preferable within a Weaver- Dunn procedure (see below) in relation to ACJ strength and functional outcome in acute ACJ accidents, had greater chance of early post-operative complications in contrast to the Weaver-Dunn procedure and also the need for future operation to remove any metal work in and about the ACJ. They recommended the procedure, especially in those with failed conservative management.(2) Distal clavicle excision with soft tissue reconstruction (Weaver- Dunn).

This procedure involves resection of this distal clavicle followed by discharge of the CC ligament from its attachment on the acromion. The end of this ligament is then connected to keep it at a position. Transfer of the conjoined tendon, where the half of the tendon is transferred to the distal clavicle, has been described. Since the operation CC ligament is left undamaged transfer of the tendon has been argued to be superior to the Weaver — Dunn technique.(3) Anatomic coracoclavicular reconstruction (ACCR).

The ACCR procedure entails a diagnostic Shoulder arthroscopy and arthroscopic distal clavicle excision. The AC ligament tied into the distal clavicle via two drill holes and is dispersed from its own acromial insertion. An autograft (donor site being the gracilis or semitendinos) or an allograft is then looped underneath the coracoid and through two drill holes in the clavicle. The graft is then tied in a figure-of-eight to itself Fashion or adjusted to the clavicle with interference screws. Several biomechanical studies are completed which illustrate that ACCR produces anterior and approximates the CC ligament complex’s stiffness.(4) Arthroscopic suture fixation.

Two Kinds of surgical techniques for Preventing the CC ligaments exist. The technique involves utilizing two anchors. The suture anchors tied over a bone bridge at the clavicle and are fixed in the coracoid. Included in the procedure the CC ligament is transferred. The kind of procedure involves utilizing two apparatus to reconstruct the CC ligaments and coracoid.Post-Operative Rehab

In spite of the surgical process used, the postoperative rehabilitation protocol will probably be similar for all types. The point if difference is going to be that if screw/plate fixation was utilized these will be removed at around eight weeks.Stage 1: protection and Immobilization (0-6 months).

The vast majority of surgeons would request a conservative six-week interval of sling that is complete immobilization to permit tissue recovery that is full with no undesirable stretch on enhancement apparatus or the ligaments used in surgery. This differs with other shoulder surgeries like shoulder reconstructions and rotator cuff repairs. The concern with sling removal in the first phase is the burden of the arm along with scapular provide a substantial traction force to the ACJ, and when that is allowed to happen in the first phases, then the ACJ may wind up getting excessive post-operative laxity. Most surgeons will urge no pendulum in the initial six weeks rather than permit the arm to be unsupported whilst in the position to prevent this. The goals so at this point are:1. Allow recovery of soft tissues;

2. Reduce pain/inflammation;

3. Early protected range of motion;

4. Retard muscle atrophy in scapular stabilizers.

The sling can be removed for cleanliness purposes. At two weeks post-op, the patient can begin passive range of motion (therapist- guided) or active assisted (patient-guided) flexion and abduction moves whilst lying in supine. All these abduction and flexion movements are gradually progressed per week two to six to 70 ° as pain permits. Normally internal and external rotation can be pushed to the limits so long as pain permits. Because this movement produces the best amount of strain on the 20, Extension motions are avoided in this phase.

Soft tissue function to the pec major/ minor, subscapularis and the latissimus dorsi if the arm could be abducted off to expose those muscles are often started early. Due to the restriction on pendulum exercises at the shoulders that are ACJ-reconstructed, the arm tends to ‘adhere’ to the side fairly easily as a result of soft tissue contracture and adhesive capsulitis from the shoulder joint. Consequently, if the therapist is able to get into the shoulder , then gentle passive mobilisations of the shoulder joint (bodily in addition to attachment) are allowed for the glenohumeral joint.

Scapular setting exercises can be performed in a confirmed position with the sling in situ. Allow pain ranges that are free of retraction and melancholy. These could be held as 10-second isometric contractions. This can be enhanced with muscle stimulators put on the trapezius and the stimulator set to an ‘atrophy’ mode.

Similarly, muscle stimulators may be utilized on the deltoids and pec in an ‘atrophy’ style. In the patient, lie May start gentle isometric shoulder Turning and abduction exercises in four weeks post operative.

Exit criteria for stage 1

1. Pain and inflammation in the ACJ.Stage 2: recover range of movement (7-12 weeks).

The Main goals in this point are:1. Gradual growth in range of motion;

2. Increase in isometric strength;

3. Maintain pain-free inflammation and ACJ.

The sling is discarded at six weeks . Because of the restrictions placed on movement in the first 6 weeks, the progression of motion is to permit abduction and active assisted flexion then progress to only in weeks 9 through to 12. Rotation movements with the arm from the side could be improved unrestricted nonetheless, extension remains prevented until 10 weeks post-op. It’s expected that the patient will have attained 90\% of range of movement into flexion, abduction and hands.

Isometric deltoid, lat dorsi and pec important can be progressed at this stage in places; spinning potency could be worked with therabands through variety. Likely lying scapular retraction and depression drills can be improved in this stage.

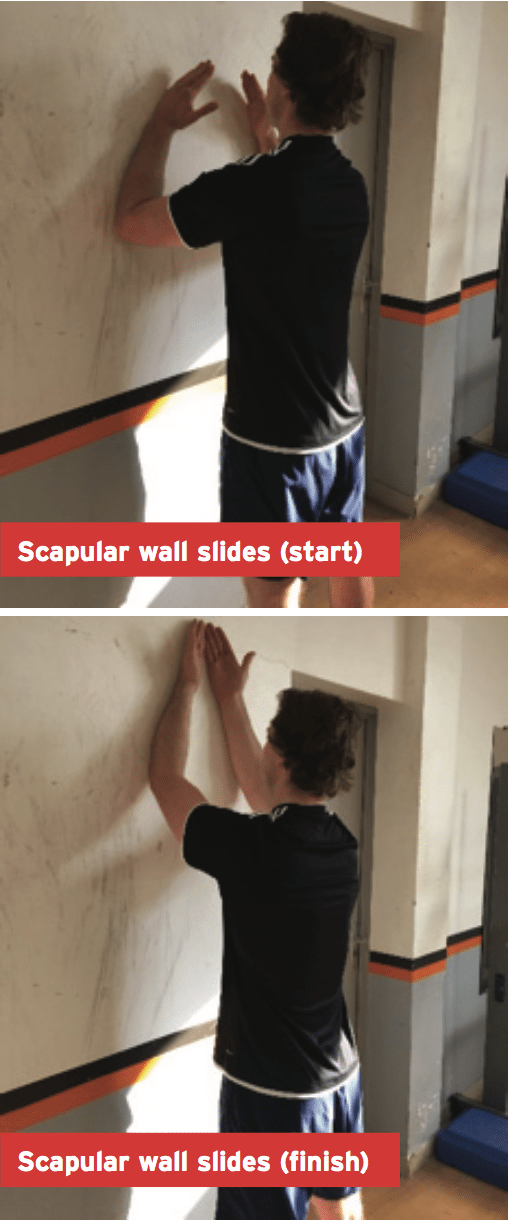

Since the patient achieves comfortable ranges of shoulder flexion, gentle wall slide exercise can be started to strengthen the serratus anterior. To execute a wall slide exercise (see image below) start with the forearms connected with the wall. Slide the forearms up the wall gradually externally rotating the arms/forearms on the way upward. This will produce scapula upward spinning and protraction to activate a necessary muscle in the control of scapula motion, the anterior.

Exit criteria for stage 2

1. 90 + % are achieved by Range of movement.2. No pain in ACJ one hour post- exercises.

3. No night pain in the ACJ.

4. Pain-free running at rate.

Stage 3: strengthening phase (13-16 weeks).

The aims in this point are:1. Regain whole selection of motion.

2. Regain 90+% pre-injury yanking power.

3. Regain 70 pushing against strength.

4. Neuromuscular control.

5. Integrate ability components.

Range of movement that ought to be close to 90+% in 12 weeks is now pushed into end of variety rankings. This can be done with a great deal of athlete directed self-stretching for the worldwide mobilizers such as rotator cuff flexibility in infraspinatus and pectoralis major dorsi. What’s more deep tissue myofascial releases to muscles as well as ACJ and glenohumeral joint mobilisations can be used to enhance arthrokinematics of the affected joints.

Traditional strength work improved or is now begun if started. As a guideline, regaining strength in an ACJ is similar to regaining strength in a joint. It should progress based motion instructions. The order of movements directions that can be improved, and a direction added each week are:

1. Horizontal pulling (as an example, seated rows, susceptible flyes, susceptible pulls, 1 arm rows).

2. Vertical drawing (close grip pulldowns, 1 arm pulldowns, lat pulldowns, chin up variants).

3. Horizontal pushing (push-up variants, bench/dumbbell/cable presses, incline bench).

4. Vertical pushing (dumbbell/barbell shoulder press, lateral/front increases).

5. PNF diagonal patterns (flexion/ abduction/external turning to expansion/ adduction/internal rotation).

It’s anticipated that the end of week 16 has the majority of the movement directions re-introduced however the strength of the pushing movements will just be around 70 percent of pre-injury levels. What’s more, any heavy traction movements to the shoulder for example deadlifts are avoided at this stage. Deadlifts with the scapular stored in retracted positions may be started, but most of the posterior chain strength operate will need to be performed away from deadlifts.

Medium to high level proprioceptive work can be incorporated into this stage with exercises for example:

1. Ball arm wrestle.

2. Push-ups on instable surfaces.

3. Kind shoulder exercises.

For the contact sport athlete involved in kind sports such as soccer, AFL skills are now able to commence in situations that are non-contact.

Exit criteria for stage 3

1. Complete painless variety of movement.2. Pain Free Scarf test.

3. Pulling on strength 90.

4. Pushing strength 70% pre-injury.

5. Pain-free running at full speed.

Stage 4: return to game stage (16-24 months).

The goals in this stage are:1. Maintain painless full range of movement.

2. Regain 90+ strength.

3. Integrate back into training.

This phase is a continuation of stage 3 in the athlete is still currently progressing back to shoulder strength whilst in increasing return to training. Pushing motions can be really progressed to regain 90+% of pre-injury strength. The athlete must have complete painless range of shoulder flexion, extension, abduction, hand behind back and flat flexion (scarf test).

If the athlete is involved in a contact sport like American Football, AFL, the decision to begin contact that is controlled is also a choice based on certain criteria. Before starting contact, the athlete should Have the Ability to perform:

1. Pain-free clap push-up;

2. Bench dip.

Both of these movements impose a tensile and compressive pressure on the ACJ they are good screening movements if the ACJ has recovered from injury and surgery to ascertain.

Exit criteria for stage

1. Complete painless variety of movement.2. Pain-free scarf test/clap push-up/ seat dip

3. Pulling on strength close to pre-injury that is 100 percent.

4. Pushing strength 90 percent+ pre-injury.

5. Completed contact training.

Return To Contact Training

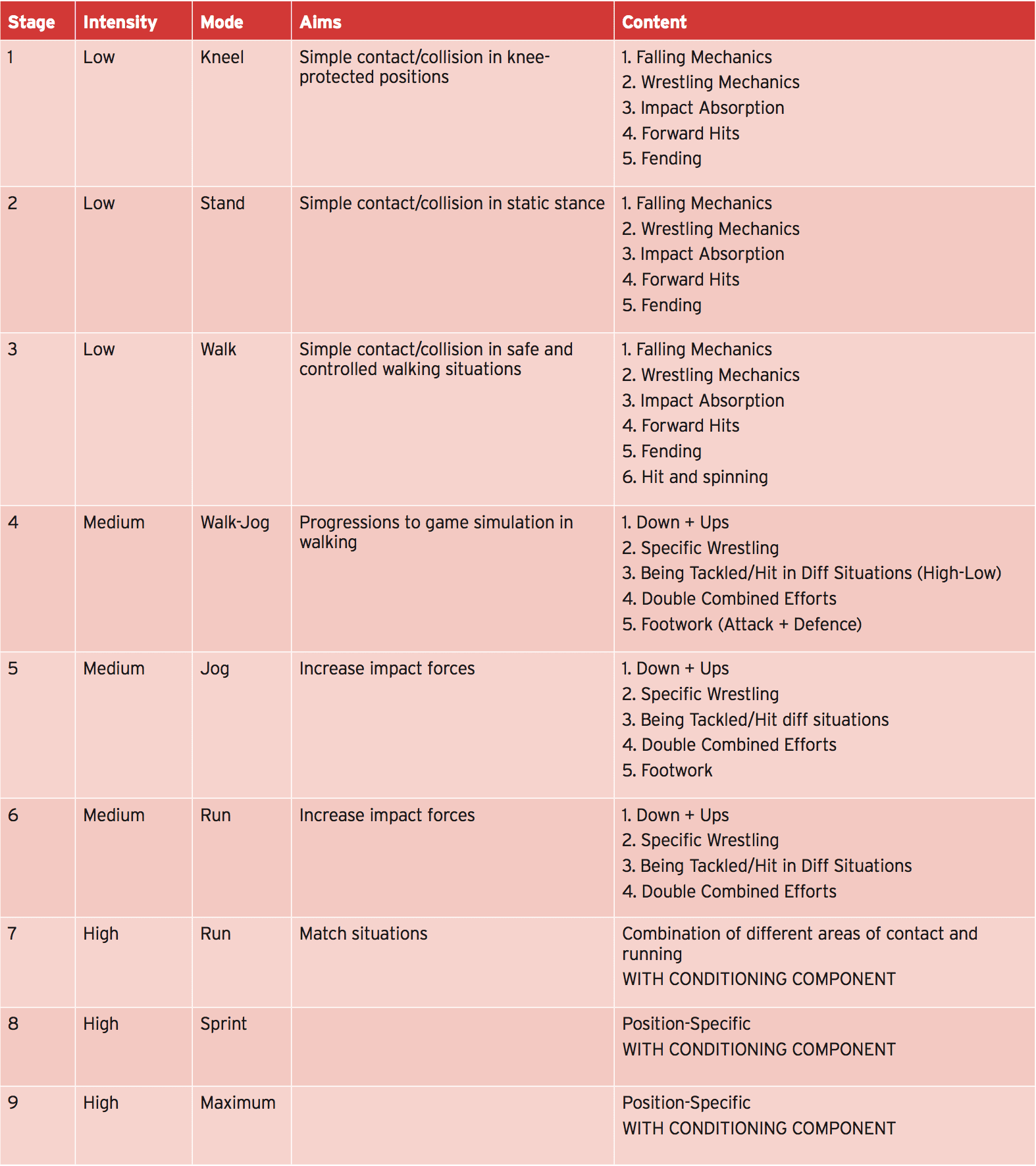

Staging an athlete back into a training situations that are competitive needs a development of drills and skills that resemble the demands of the contest whilst still allowing appropriate protection of their shoulder/ ACJ at crucial stages of recovery. A logical means is to alter the training environment from safe and controlled situations initially to events that are more advanced as they progress. For example, starting in then progressing to standing kneeling positions, walking and walking positions allows the athlete to practice contact elements without fear of further ACJ injury.Below is a good example of how an ACJ-injured athlete would progress contact situations for a combative sport such as combative sport like football.

Conclusion

Returning back an athlete in the surgically reconstructed ACJ is similar in time and material period to additional shoulder surgeries except for a couple of differences. First, the protection stage is far more important to stick to in the athlete as ancient motion from the sling may result in grip on the joint which may render the ACJ hyper-mobile from the post- operative phase. The progression of range of movement is different to shoulder operation because rotation movements are permitted nonetheless, extension is averted for the first ten weeks. Following these differences, return to game guidelines and the remainder of the rehab process is similar in content to shoulder surgeries in the development of range of motion contact in instruction.The stages of rehabilitation is going to be highly dependent on the sport. For the throwing athlete, proper throwing needs to be woven with all all the pitching, tennis, golf and swimming, similarly into the phases of rehab. The touch sports athlete includes a bunch of other complicating integrations that aren’t a problem with athletes that are non-contact.

Most of the ACJ-repaired athletes may return to sport participation within six months of operation based on the sport played. Some sports might be back competing in 14-16 months post- operative. Power athletes may take considerably longer and sometimes up to nine months post-operatively.

References

1. Bontempo NA and Mazzocca (2010). Biomechanics and treatment of acromioclavicularand sternoclavicular joint

injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 44. 361-369.

2. Bearn JG (1967) . Direct observations on the function of the capsule of the stemoclavicular joint in clavicle support. J Anat; 101:159-170.

3. Bosworth BM (1941). Acromioclavicular separation. New method of repair. Surg Gynecol Obstet; 71: 866-81.

4. Calvo E et al (2006) Clinical and radiologic outcomes of surgical and conservative treatment of type III acromioclavicular joint injury. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery.15(3); pp 300-305.

5. Fukuda et al (1986) Biomechanical study of the ligamentous system of the acromioclavicular joint. J Bone Joint Surg AnL 1986;68:434-440.

6. Headey J, Brooks JH, Kemp SP (2007). The epidemiology of shoulder injuries in English professional rugby union. Am J Sports Med;35: 1537–43.

7. Peterssen CJ (1983) Degeneration of the acromioclavicular joint. A morphological study. Acta Orthop Scand. 54; 434-438.

8. Richards RR (1993). Acromioclavicular joint injuries. Instr Course Lect. 42:259-269.

9. Rockwood CA (1998) Disorders of the acromioclavicular joint. Rockwood CA and Matsen F. The Shoulder. Philadelphia. USA. Saunders. 483-553.

10. Sugathan HK and Dodenhoff RM (2012) Management of Type 3 Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocation: Comparison of long-term functional results of two operative methods. International Scholarly Research Network ISRN Surgery Volume 2012, Article ID 580504, 6 pages.

11. Tossy et al (1963) Acromioclavicular separations: useful and practical classification for treatment. Clin Orthop Related Research. 28; 111-119.

12. Warden SJ.(2005) Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors: beneficial or detrimental for athletes with acute musculoskeletal injuries? Sports Med;35: 271–283.