Acetabular labral tears of the hip are just one of the more challenging accidents for clinicians to diagnose and manage. Chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez looks at what the recent signs indicate…

Physical disturbance of the hip joint is often related to a acetabular labral tear (ALT) and may be associated with intra- articular snapping hip syndrome around 80% of instances(1). Labral tears affecting the hip joint are prevalent in 22-55% of patients having hip or groin pain(two) and evidence indicates that an untreated ALT may predispose an individual to premature degenerative arthritis(3), which has created a widespread interest within clinical practice and the literature.)

The examination and imaging techniques with guessed ALT’s have improved greatly in the last decade, but an appraisal of a labral tear still remains complex. The purpose of this article therefore is to review the anatomy and biomechanics of the acetabular labrum, the evaluation techniques and the treatment and treatment options available.

Anatomy & Biomechanics

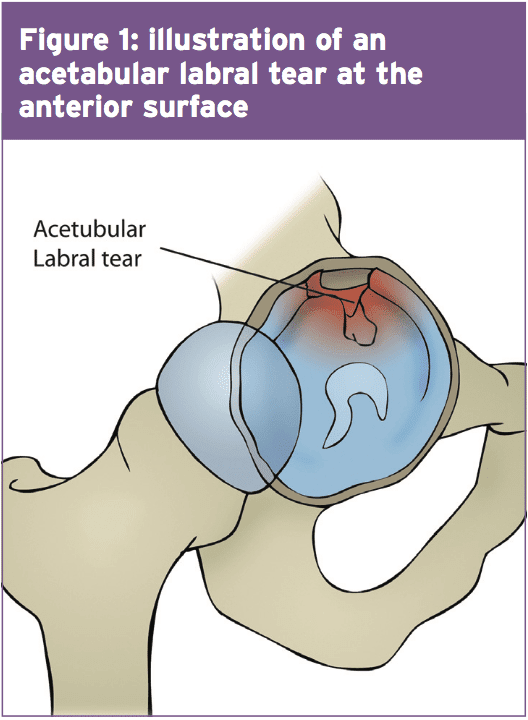

The labrum increases the surface area of this acetabulum by 22\% and the volume by 33\% and it works by forming a seal for the mind of femur to rotate (see Figure 1). From a cross-sectional view, the labrum is triangular in its appearance with the extra articular zone being dense connective tissue which has a rich blood supply and the intra thoracic zone chiefly having no blood source (3).

At the extreme end ranges of hip motion, The labrum is worried by compressive forces -a rip at this point can affect joint stability and load distribution(2). What’s more, pain receptors have been located in the superior and anterior areas, and the labrum is therefore regarded as a pain generating structure(4). It is in the anterior surface (Figure 1) where an ALT is most at risk due to the compressive forces at the end stage of hip flexion (5). Also of note is that structural abnormalities like retroverted acetabulum and coxa valga happen to be observed concurrently in patients (87 percent) with labral tears (6).

Examination & Assessment

An ALT is complicated to diagnose and even though recent improvements in medical imaging and evaluation methods, one report identified that generally, patients seen three healthcare providers and also waited for 21 months before an ALT was correctly diagnosed(3). When examining a patient with a suspected ALT, clinicians should also consider femoro-acetabular impingement (FAI) and acetabular cartilage damage, and MRI imaging ought to be used to encourage the clinical findings(3).Acetabular labral tears are often the consequence of cutting, pivoting, twisting as well as repetitive movements into end range hip flexion usually found in tennis players, footballers and runners. This might help explain why researchers in the New England Baptist hospital in Boston, USA found that from 436 arthroscopies of labral tears in athletes, 273 (62 percent) also had articular cartilage damage(6). However the specific mechanism of an ALT injury may not always be apparent to the individual, as it may be degenerative, congenital or traumatic in its incidence(two).

During a physical assessment of a hip related injury it is essential to be vigilant for a non-musculoskeletal associated pathology. Hip associated pain may be associated to an ALT but might also be the result of spinal spine or pelvic girdle dysfunction, abdominal viscera and the peripheral nervous system(two). Pain at rest, night pain, fever, night sweats, and generally feeling unwell and unexplained weight loss are indicators of a non musculoskeletal pathology and require referral for further evaluation by a healthcare provider(2). Reiman and colleagues also indicated that hip pain may be associated with the abdominal and pelvic organs and a musculoskeletal injury must not be assumed(two).

A patient with an undiagnosed ALT may also pose with synovitis and joint inflammation and might adopt places of hip flexion, external rotation and minor abduction, which place the capsule at its largest potential volume to reduce the strain on the labrum. Positions including flexion and adduction are found to raise the total load on the labrum and this are purposely avoided.

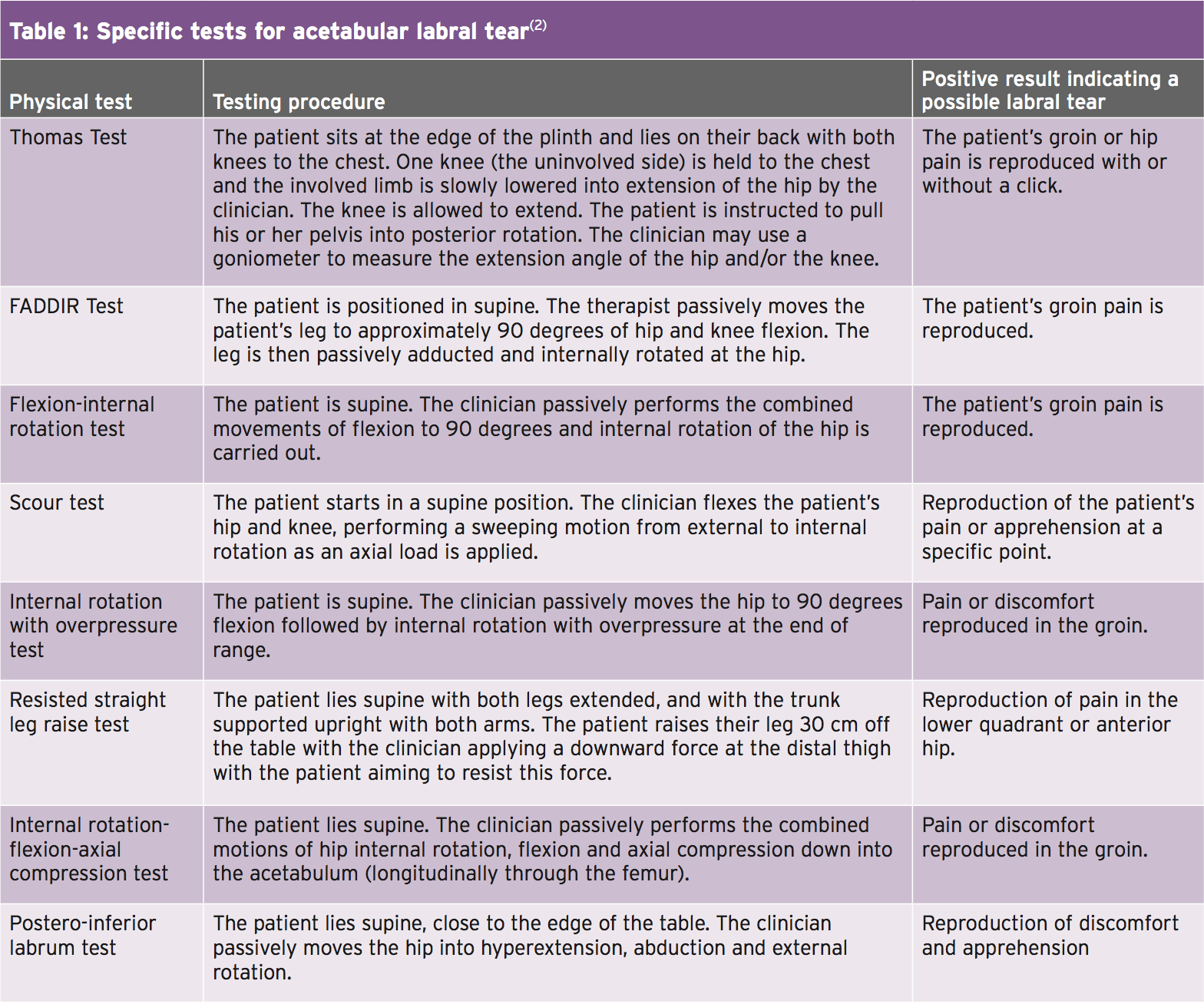

The combined impingement position of flexion, adduction and internal rotation, known as ‘FADDIRs test’ increases stress into the labrum, but can also be a contributor to intra-articular hip pathology(7). Patients using an ALT may also complain of pain on squatting, stepping up together with the joints that are involved, or sitting in a seat with the buttocks positioned lower than the knees. In addition a patient with an ALT is not likely to extend fully in the hip during gait because this places the greatest load to the anterior joint capsule and consequently stress to the anterior labrum. Table 1 outlines the many positions and specific tests for determining an ALT.

Surgical Vs Non-Surgical Treatment

Hip arthroscopy is a widely used treatment adjunct in patients presenting with an ALT symptomatic of more than four months and confirmed by MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or MRA (magnetic resonance arthrogram)(4). Hip athroscopy for an ALT may comprise either labral debridement or labral repair. In contrast to surgical repair there’s limited support for conservative treatments for an ALT. Nevertheless researchers from Sao Paulo, Brazil have provided a case number of four patients that underwent a rehabilitation program for an ALT without operation(8). The four patients have been diagnosed with an MRI scan and failed a 3-phase program together with the first being pain management, hip and trunk stabilization, re-education and correction of abnormal joint movement. Phase two focused on restoring normal range of motion, muscular strength and beginning sensory motor training. The last phase of the rehabilitation program focused on preparing the athlete for a return to sport.The four patients involved in the case series were in their mid twenties and were from both sedentary and athletic wallpapers(8). The outcomes of the conservative rehabilitation program yielded a decrease in pain levels, functional improvement and correction of muscle imbalances. Increased muscle strength was noted using the hip flexors increasing from 1% to 39 percent, hip abductors increasing from 18 percent to 56% and the hip extensors rising from 68% to 139%. The potency of the research is limited, with the case series being just four sufferers but nevertheless could offer an excellent proactive strategy whilst a patient is anticipating an arthroscopy.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation following surgical repair of an ALT is limited regarding its signs, both inside the surgeons own rehab protocol and the therapist’s experience(4). Researchers from Tampa, USA, devised a rehab protocol for the patients to follow the following protocol is mostly predicated upon(4):Stage 1 (weeks 1–4)

- After labral debridement, weight bearing ought to be limited to 50% partial weight bearing for 7-10 days, using flexion restricted to 90° for 14 days. A labral debridement also has no limits post- operatively to abduction, external or internal rotation or extension. In contrast a labral repair should keep non-weight posture or toe-touch weight bearing for three to six weeks post operatively.

- The ranges of motion should be much more conservative in labral repair, while external and internal rotation must be invisibly transferred into for 3 weeks. Do note that if other procedures are carried out such as microfracture fix afterward the post-op protocol might well differ.

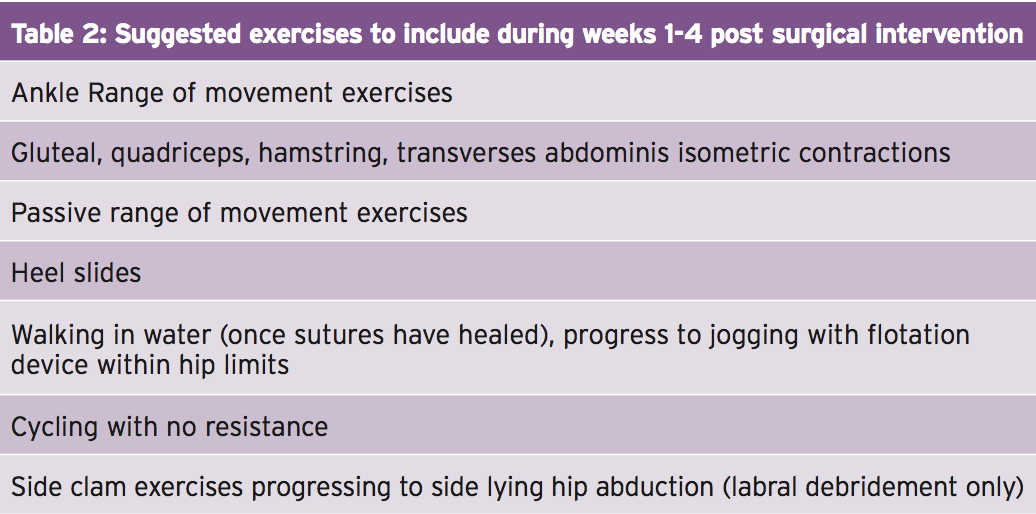

- Throughout the immediate post-operative period, it is crucial to handle pain, decrease swelling and initiate premature motion in the affected limb, however it’s also vital to concentrate on additional factors such as core activation and abductor control (see Table 2). A strong association exists between decreased action of the hip abductor muscles and lower kinetic chain injuries, including anterior knee pain(9). As a result, once the fashionable ranges are available, it is essential to encourage a patient to trigger the profound hip and backward stability muscles to prevent secondary injuries from happening.

Stage 2 (weeks 5–7)

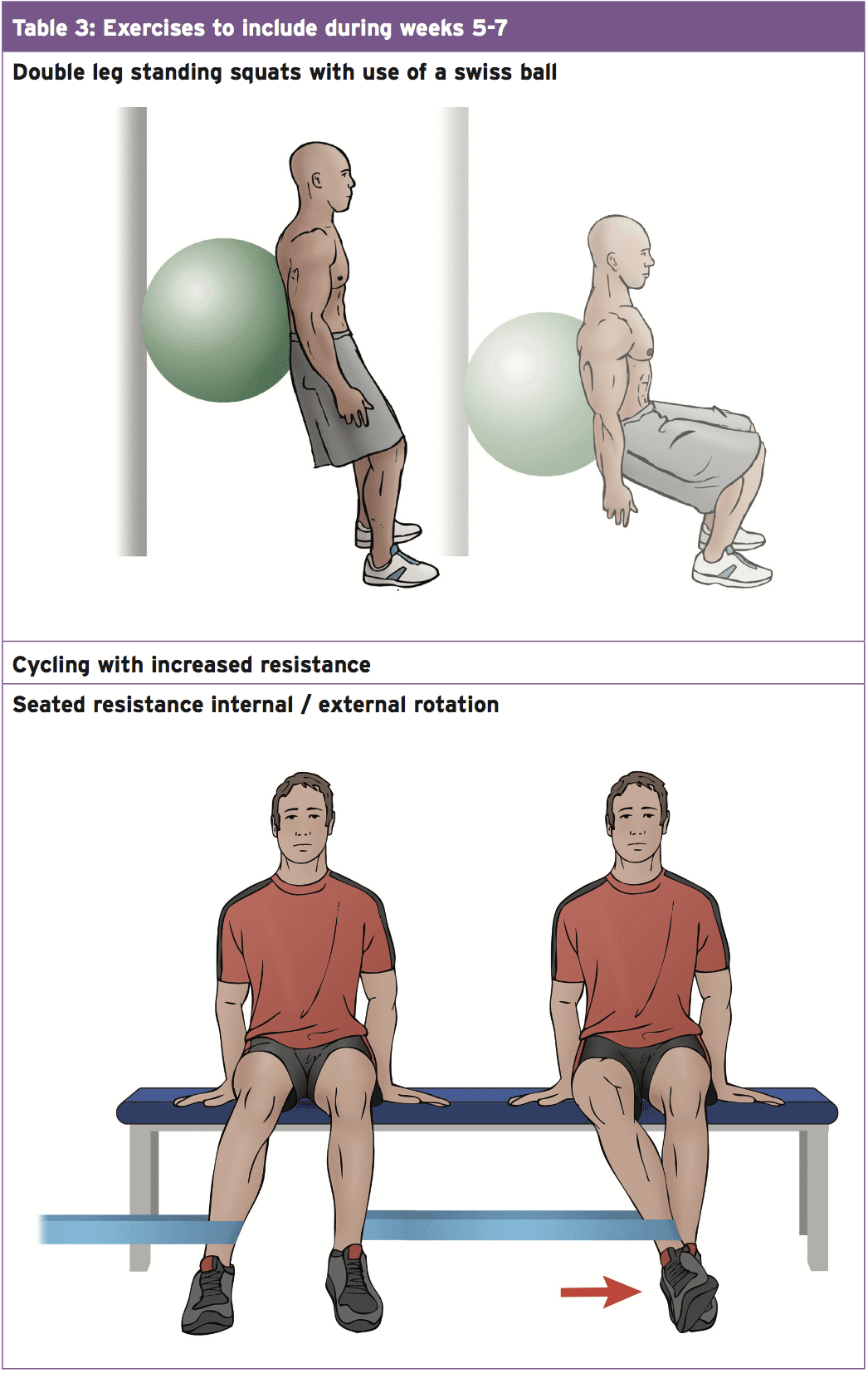

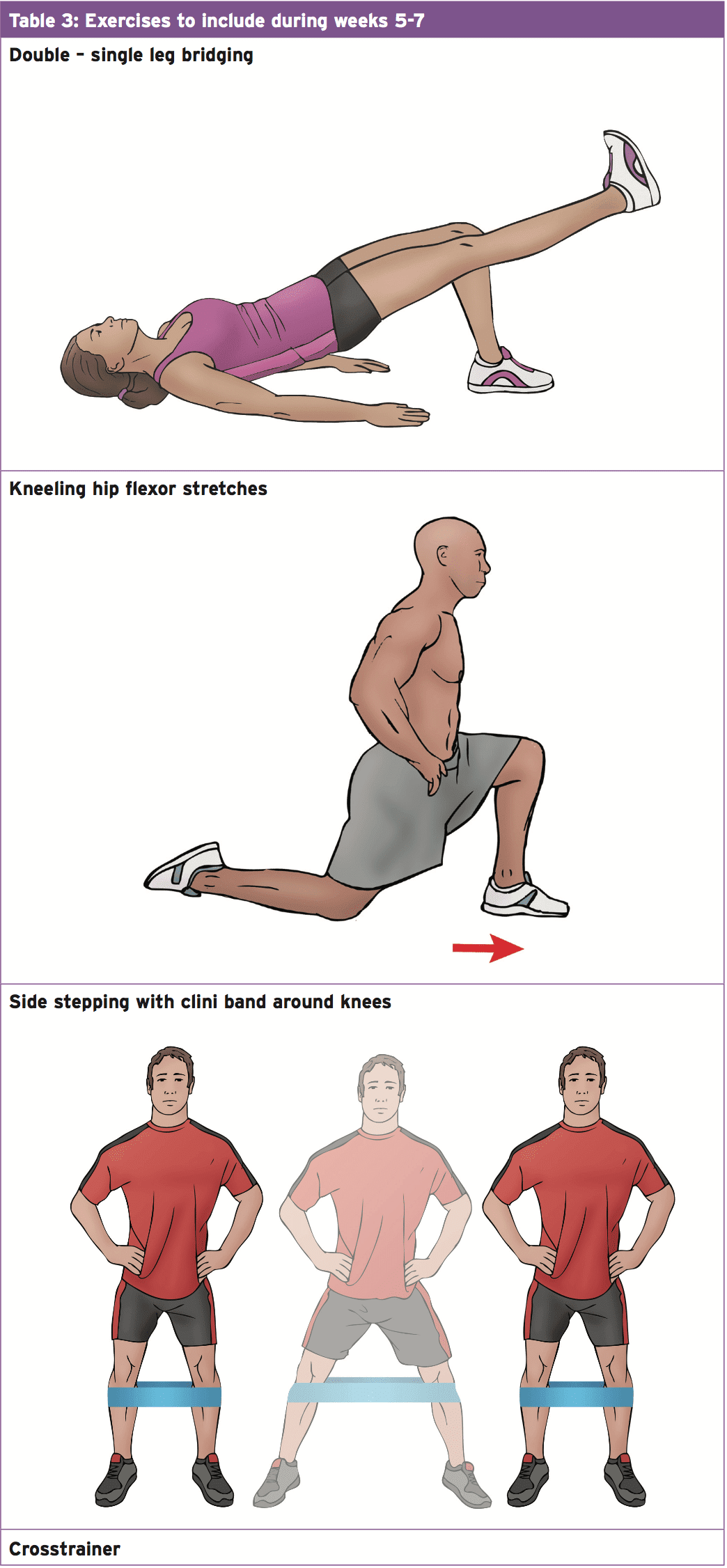

- Throughout this stage of rehabilitation it is essential to restore normal range of movement with a focus on increasing strength and growing flexibility of the muscles crossing the fashionable join (see Table 3).

Stage 3 (weeks 8-12)

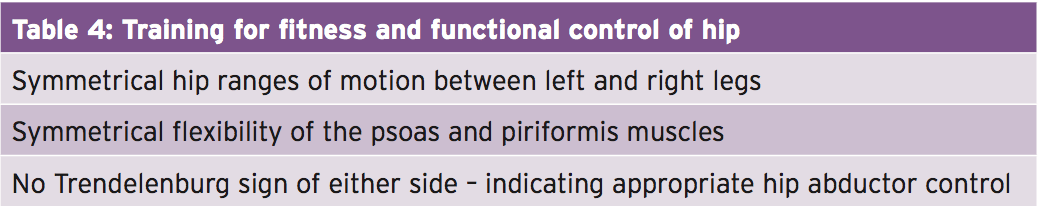

- This stage is a great opportunity to develop cardiovascular fitness and operational control of the hip. Functional stability exercises should be carried out at a standing position with an emphasis on maintaining and enhancing equilibrium ready for athletic participation. Exercises to include within this phase are walking lunges, lunges with back rotation on the front leg and a Swiss ball system suitable for challenging the core muscles. Garrison and colleagues(4)) have provided criteria (Table 4) to follow ready for development to stage four which is planning for return to sport.

Stage 4 (months 12+)

- This phase of the rehabilitation program is the opportunity to be preparing the athlete for their return to sport, and especially their position it’s particular tasks. If the athlete is a defender in football, they ought to be replicating tasks unique to their own position. Before the individual resuming full instruction, they have to have the ability to demonstrate the same neuromuscular controller as the uninvolved side.

Summary

A guessed ALT with the background and clinical texts should be verified using an MRI or MRA to affirm the presence Of a ALT but also to exclude any referred Pain masquerading as a Psychological injury. An appropriate rehabilitation Program ought to be started Immediately to improve hip and back control and to handle pain. This will enable the individual to proceed through the Surgery with increased simplicity having already Commenced a rehabilitation program.References

1. Arthroscopy. 2005, 21:1120-1125

2. Br J Sports Med, 2014: 46 (4), 311-319

3. J Bone & Joint Surg Am, 2009, 91, 701–710

4. J Arthroplasty, 2001 Dec; 16 (1), 81-7

5. North American J of Sports Phys Thera Nov 2007, 2, 4, 241-250

6. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. July 2003,123 (6), 283-8

7. Am J Sports Med 2011; 39

8. J or Ortho and Sports Phys Thera, May 2011, 41, 5, 346 – 353

9. J Athl Train. 2011 Mar-Apr; 46(2): 142–149