Chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez assesses some of their most common problems confronted by divers and also how they can be avoided.

Evidence exists that people dove for game as far back as 480 BC(1). From the seventeenth century, their maneuvers were executed by functionality gymnasts from Sweden and Germany at the beach within the water. Diving, as we know it today, began in England and by 1904 men diving. The 1908 Olympic games included men’s platform diving. Women’s ‘plain’ diving began in 1912 and ‘fancy’ diving at the Olympics. Today’s Olympic diving events include the individual and dives, and the 10-meter platform individual and dives for both men and women.

Into The Deep

Dives are broken up into the following classes: forward, backward, reverse, inward, twist, and handstand. Once in the atmosphere, divers assume a directly (no flexion), pike (flexion in the hips), tuck (bent knees and hips), or free (a combo of all three) place. Based on their age, divers perform a set variety of optional and required dives.The dive is comprised of 3 parts: the take-off, flight, and entry. The movement that occurs while the diver is in contact with the board or platform is considered part of the take-off. On the springboard, the take-off for reverse or front dives starts with the approach toward the conclusion of the board. The jump on one foot at the board’s end is called the hurdle. When the board is depressed, the press occurs and the air is rushed into by the diver. The take-off for backward and inward dives that are springboard requires swinging the arms while performing the press with the legs without the hurdle, and standing at the conclusion of the board, to initiate movement. If the dive is from a platform, then of the force is generated by the diver for the take-off by pushing off the platform, either with the arms for a handstand dive, or the legs for a standing dive.

The flight portion of the dive begins when the diver leaves the springboard or platform and ends when he contacts the water. The pikes, tucks, and twists are initiated and executed during the flight. The entry phase contains impact with the ensuing movements and the water, called the swim-out, which help execute a entry.

The diver attempts to ‘punch a hole’ in the water. The impact occurs with arms and hands palms and wrists or with the hands. The elbows locked and are extended and the arms are in line with the ears to protect the head and neck. At impact, the scapulae abduct to guard the shoulder joints and absorb impact forces. The initial impact produces a hole in the water and the diver’s goal is to slide his body within this hole in a position, resulting in splashing and minimal forces on the body.

The velocity of the diver at impact ranges between 8.4 m/s to 16.4 m/s depending on the height at take-off(1). Therefore, the resulting forces at impact range from 2.0 m/s2 to 2.4 m/s2(1). Researchers compare the forces experienced at impact to diving from a 1.2-meter platform and landing on a difficult surface(1).

The diver’s body is fully submerged within 1.28s — 1.40s after impact(1). After impact, the diver begins the swim-out. These manoeuvres enable him to ‘save’ the dive if the entry happens to over- or under-shoot vertical. Swimming in the dive’s direction helps and provides a motion align the body to vertical. Doing so results in hyperextension and excessive shoulder flexion.

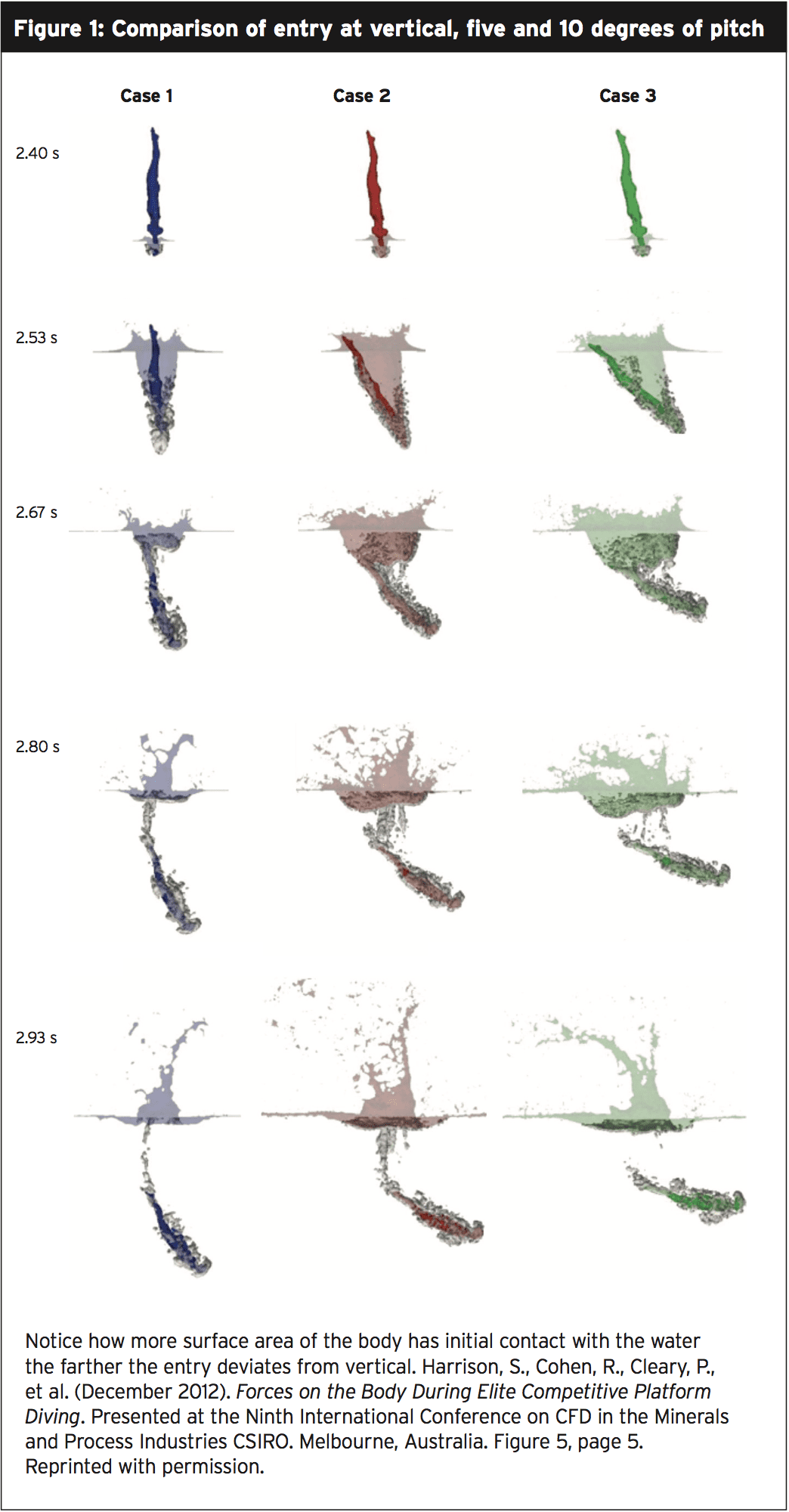

To study the forces experienced when the dive entry deviates from vertical, researchers in Victoria, Australia, digitised the reverse pike platform dive of an Australian Olympic diver(2). The digitised version was utilized to compute dives of pitch at entry. Simulations of five and 10 degrees of variation from entry angle found that while the forces to the hands remains constant changes occur at other areas of the body.

The hole produced by the hands enables the body to enter the water and thus, stress, when the entry is done nearly vertically. As the dive deviates from vertical, the dive is shallower, the body more horizontal, and impact with the water greater (see Figure 1). The splash that is bigger is the sign.

Common Upper Extremity Injuries

As previously discussed, the hands and wrists bear the brunt of the forces encountered when diving. Employing the flat-handed entry technique, wrist dorsiflexion is experienced by the diver upon impact. Handstand push-ups to exit the pool further tax the wrists and hands and dives. Use increases the likelihood of subluxation of dorsal ganglion cysts; strains and sprains of the ligaments of the wrist and hand; tendonitis, especially of the flexor carpi ulnaris; and the bones of the wrist and hand. Fractures of the hand and wrist are uncommon but do occur when the hand strikes on the springboard or platform.Diagnosis of hand and wrist injury is most accurately made using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as both the soft tissue and bony structures are visualized. Most hand and wrist injuries respond to conservative treatment of protection, rest, ice, compression, elevation, and rehabilitation (PRICER). Divers return to competition within weeks of injury, with the utilization of taping or bracing to minimize future trauma. Rarely required intervention may be necessary for decreased function or pain.

From the hands and wrists to the shoulder girdle, the elbows permit the transmission of forces during impact. The cranium may strike at entry, or worse, fail to defend the head and neck, if the elbows flex. If impact is hyperextended at by the elbows, the ulnar collateral ligament is vulnerable to strain. Hyperextension contributes to ulnar neuritis and instability. Attention to technique and dry-land strength training protects the elbow and keep the triceps strong.

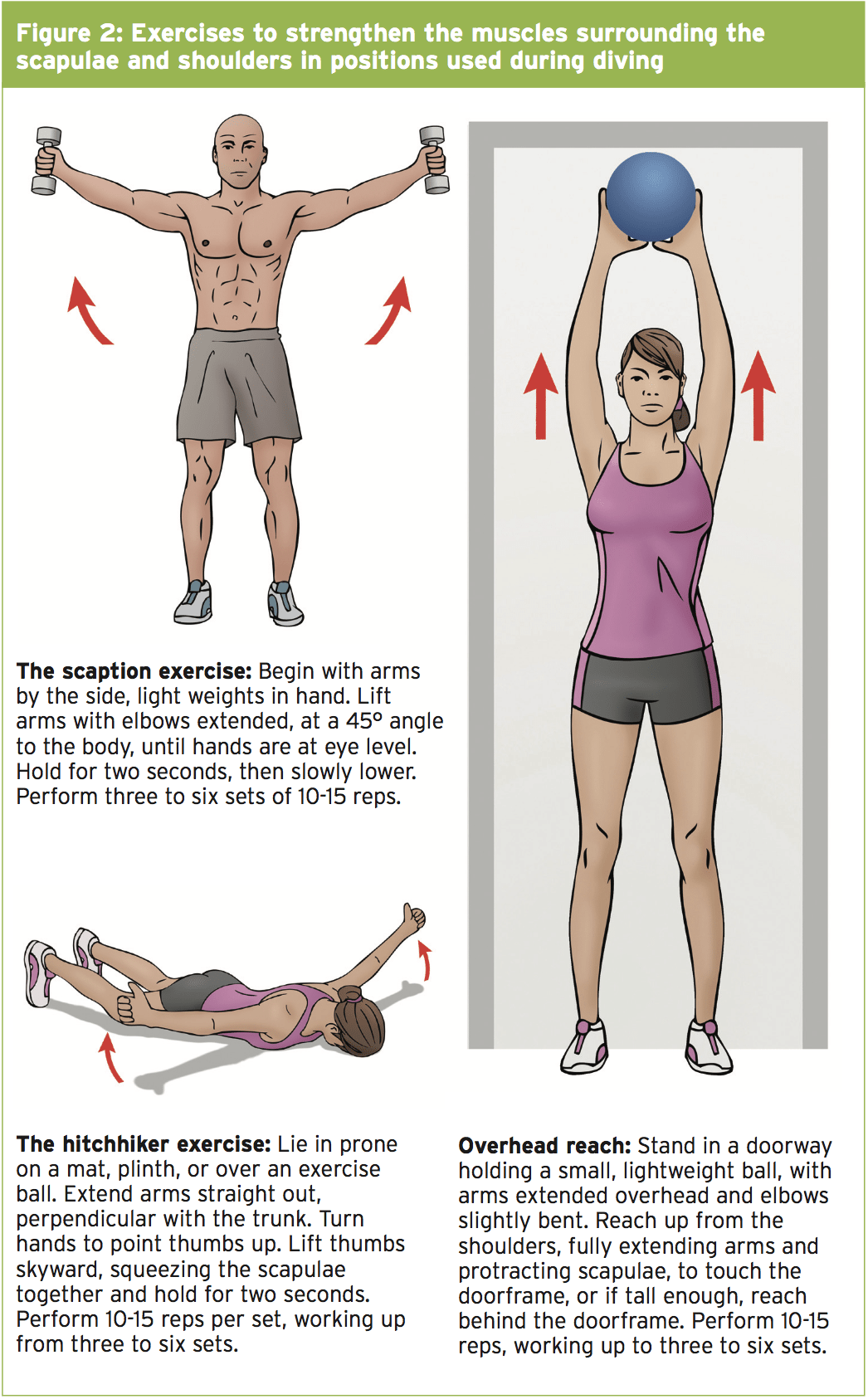

As with other aquatic sport athletes, shoulder joints are often exhibited by divers. Hypermobility may lead to instability and injury. A survey of the United States National diving team found that 80% of the members had shoulder injuries that required a week or more of rest from training(1). While frank tears in the rotator cuff are rare traction tendonitis and tears of the rotator cuff are common. Treatment of shoulder lesions is typically the same as in any population that is athletic. Scapular stability is being maintained by the key to preventing shoulder injuries. Weakness in rhomboids, the serratus anterior, and trapezius muscles contributes to humeral subluxation and instability. Exercise these muscles in functional positions, with arms extended, in addition to traditional strength training (see Figure 2).

The Back & Spine

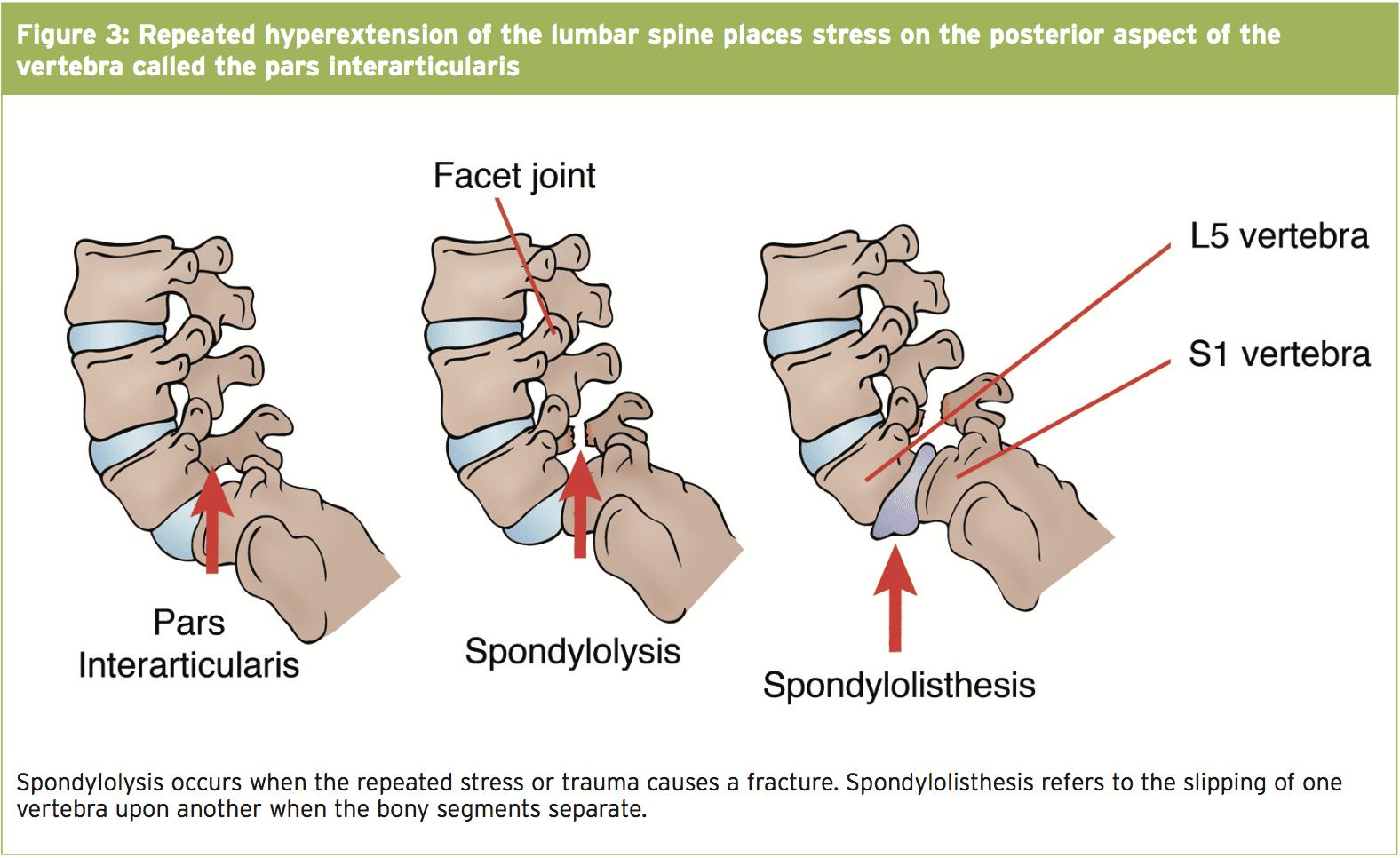

Unlike diving, cervical spine injuries are rare in competitive diving. The neck is usually protected by correct technique that is diving . Spinal injuries from diving that is competitive occur in the thoracic and lumbar spine. As the diver executes twists and tucks injuries happen as a result of stresses of the flight maneuvers. Injuries to the anterior section of the lumbar vertebrae when flexed during flight and are due to the stresses experienced at the press in springboard dives. Stress is experienced by the posterior lumbar spine at entry and take off during lumbar extension, reverse and especially for back dives; and when divers attempt to ‘save’ a dive by hyperextending the back after impact.The most common orthopaedic spine injuries in divers are lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Spondylolysis is a fracture of the pars interarticularis, the posterior-lateral region of the vertebra that acts as the bridge between the vertebral body and the interlocking facets (see Figure 3). The fracture is usually the result of lumbar extension stressnevertheless, acute traumatic hyperextension can cause a fracture. The L4 vertebra can be involved, although the most common location is in the L5 vertebra. Some athletes have congenitally weaker bone in this region and may be predisposed to fracture.

Symptoms generally occur with a grade I or grade II slip and so are treated before the severity increases. Symptoms range to nerve impingement pain radiating into hips and legs. Treatment involves rest from the offending movements (anywhere from three to six months for complete healing), occasional bracing to stabilize the fracture, and therapeutic exercises to strengthen the core stabilizing muscles. In severe cases, surgical fusion is necessary.

Diving manoeuvres push at the limits of mobility. Repeated movements may lead to irritation of the facet joints, the joints that connect the vertebrae. Generalised low-back pain that’s difficult to diagnose is typically presented with by lumbar facet syndrome. Changes to the facet joint on X-ray are subtle and might be detected using CT scans. By compressing the joint with active extension and rotation reproduce symptoms. Symptoms improve with flexion, which separates the joints. Treat facet pain with anti-inflammatory medications, rest, and physiotherapy. Consider inflammation and decrease pain to calm, if unresponsive to therapy.

Preventing Back Pain

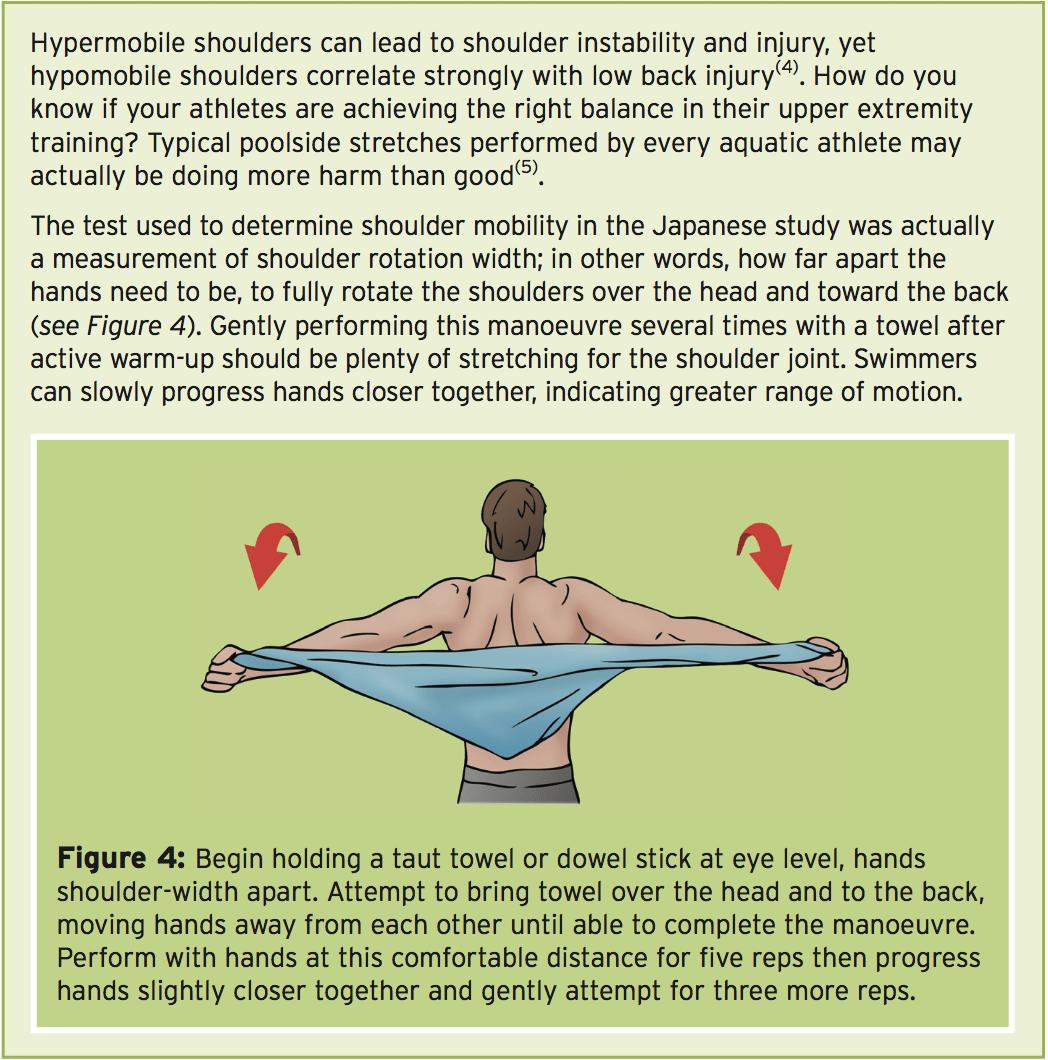

Acknowledging that low back pain occurs in significant numbers in divers, researchers in Japan evaluated 83 elite junior divers (42 men and 41 women) through a questionnaire, interview, and clinical exam, searching for clues as to causes and prevention(4). Of all of the divers, 37.3% reported low back pain. Decreased shoulder flexibility and low back pain correlated in males. Age most strongly correlated with low back pain in females, and secondarily in males. The median age of the low back pain groups was 15.6 years for men and 15.5 years for women. The median age of both male and female non-pain groups was 13.8 years.Other Injuries

Diving accidents to the legs, legs, and feet are uncommon, and mostly because of striking on the board or platform.Divers experience many of the exact same tissue injuries around the knee and ankle which athletes do, because jumping is an significant part the take-off. Treatment for tendonitis or ligament strains around ankle and the knee are just like for different athletes.

The velocity of the water entry and changes in pressure can cause injuries to the ears and eyes of divers. Ruptured membranes occur due to pressure changes underwater or if the water strikes with the side of the head. Contusions and detachments can occur when striking the water with the head. When the board or platform strikes after a faulty take-off rare but dramatic head injuries occur. Pneumothorax and contusion result from going into the water with the thorax, rather than entering vertically into the cone created by the hands.

Conclusion

The Fédération Internationale de Natation, (FINA) statistics reveal that female divers suffer the most injuries of all aquatic sportsmen, with 134.1 incidences out of every 1000 athletes(7). Diving injuries to male divers rank third in frequency of aquatic athletes, just behind water polo, with 118.6 per 1000 athletes(6). Diving injuries are caused by repetitive micro-trauma from instability overuse , faulty technique, or, more rarely, acute trauma. Divers injure back the wrists, and shoulders. Attention at entry to proper technique, together with strength training the lower and upper back and shoulders, show the greatest success at injury prevention.References:

1. Clin Sports Med. 1999 Apr;18(2):293-303.

2. Harrison, S., Cohen, R., Cleary, P., et al. (2012, December). Forces on the Body During Elite Competitive Platform Diving. Presented at the Ninth International Conference on CFD in the Minerals and Process Industries CSIRO.

Melbourne, Australia.

3. Am J Sports Med. 1997;2:248-53.

4. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:919-923.

5. Van den Hooogenband, C. R., Miller, J. A Delicate Balance in Aquatic Sports-the Shoulder. Presented at IOC World Conference on Prevention of Injury in Sport.

6. Marks, S. (2012, November). Diving Injuries and Prevention. Presented at the 2nd FINA World Diving Coaches Conference, Mexico City, Mexico.