Scientific specialist Dr. Alexander Jimenez looks at the functional anatomy of the pectoralis major along with rehabilitation treatments, mechanisms of injury & surgical options.

Introduction

First reported in the literature by Patissier in 1822 in Paris (Patissier in Kakwani et al 2007) ruptures of the pectoralis major are pretty infrequent injuries, rarely reported. It occurs in contact, body combat sports and weight training and is caused by a violent contraction of the muscle in a position like the bottom of a bench press, of stretch or in tackling in rugby/NFL. Even though a rare accident, it is becoming more common with the prevalence of weight training contact sports and body combat athletics.Anatomy & Biomechanics

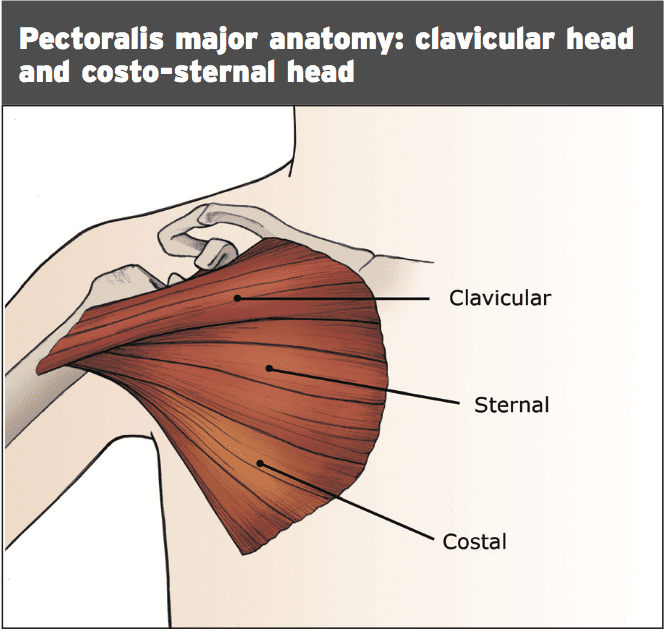

The precise insertion of the tendon has two components: upper sternal portion and the clavicular of the muscle inserts on the humerus distally below the insertion of the lower sternal and oblique fibers. The two different thoracic components efficiently ‘spin’ on every other 90-180 degrees prior to insertion on the humerus (Provencher et al 2010, Merolla et al 2012)

Wolfe et al (1992) discovered through a study using fine wire gauges the sterno-costal head and its tendon lengthen disproportionately in the last 30 levels of humeral extension compared with the clavicular head. This makes the sterno-costal head more prone to trauma and rupture because it is most susceptible to competitive stretch and also indicates that partial ruptures of the thoracic (isolated sterno-costal) is somewhat significantly more frequent rather than complete rupture of both minds.

The pectoralis major is adductor, a powerful shoulder inner rotator and flexor of their shoulder. In addition, it acts a lively global stabilizer of the shoulder in contact sport scenarios. But, Marmor et al (1961) demonstrated that the pectoralis major is not essential for normal shoulder function as other shoulder muscles may produce the necessary force for everyday tasks. Although the sedentary and elderly can perform well with conservative management, indicating that athletes will need surgical repair, it is crucial for strenuous physical activity.

The type of injuries possible to the pectoralis major contain contusion or sprain, partial tear, complete tear, muscle origin tear, muscle belly tear, musculotendinous junction (MTJ) or muscle contractions itself (Tietjen 1980). Often rupture of both heads isn’t seen, with just the fibers of this sterno-costal head. Total ruptures incorporate an avul- sion of the enthesis.

Demographics & Incidence

Rupture of the pectoralis major tendon is a rare event, but has become more prevalent in the last few decades together with the growing professionalism of contact sport participation and increased participation in weight training. It is more common in the ages of 20-40, suggesting that athletic behavior (heavy lifting and contact sport participation) is the main underlying risk variable in pectoralis tendon rupture. Furthermore, it appears to affects men much more than females indicating that athletic behavior may be an underlying factor.Hanna et al (2001) found that in the cases they studied, 50 per cent were originally elicited by acute setting medical doctors, consequently understanding the presenting symptoms and signs is crucial for medical personnel handling acute soft tissue injury particularly in the athlete. It has been shown that delay in operation because of misdiagnosis will lead to outcomes.

Mechanism Of Injury

Injury is generally brought on by a sudden forceful overload of the muscle in a maximally contracted posture, or more frequently due to direct contact whilst it is in a position. Whereas blows tend to injure the muscle belly Stretch and load type injuries often result in injuries to the insertion and musculotendinous junction.Mechanisms of injury include:

1. Tackling in contact sports such as NFL and rugby;

2. Bench pressing, particularly at the bottom or if the weight is suddenly bounced off the chest or if the lifter arches the spine to avoid ‘going over’;

3. If the arm is externally rotated and extended along with there is a stretch applied because of a fall or jolt; e.g. water skiing/windsurfing

4. If the arm has been caught in an awkward positioning, e.g. wrestling.

It has been suggested that a normal healthier tendon is resistant to rupture and that a focus of degeneration needs to exist in order for the tendon to neglect and rupture (Kannus and Jozsa 1991). Weight training may matter the tendon as well as also the prevalence of rupture follows the onset of a tendon degeneration.

Signs & Symptoms

Patients complain of a sudden sharp pain in the upper chest over the shoulder and the mechanism is generally typical, together with the arm caught in a firmly contracted and stretched position such as tackle at the base of a bench press or in contact game. This may be related to a ‘ripping’ or ‘popping’ feeling.The victim will protect the shoulder and be reluctant at the days after ecchymosis may develop in the axilla and upper bicep area and to move the shoulder because of pain.

Examination will demonstrate a thin axillary fold or a sulcus where the deltoid and pectoral muscle cross or groove. Active contraction of the muscle will reveal a proximal bulging from the anterior chest wall. This can be accomplished by asking the individual to press the palms together forcefully in front of your system (prayer position) as this elicits an isometric contraction of this muscle. Often a defect will be present in the anterior chest wall.

Range of shoulder movement into abduction and external rotation is going to be pain-limited- lived and range of motion might be recovered. However, weakness into internal rotation will be present particularly when internal rotation is analyzed using the arm in neutral rotation (with the forearm and arm postured like holding a pistol).

Imaging

Plain x-rays prove inconclusive, but it has been revealed that the absence of a shadow that is pectoral may indicate a rupture of their tendon that is pectoral. The tear may be visualized by ultrasound and this may show thinning of the muscle and echogenicity that is uneven. CT scan may reveal disruption of the muscle contractions.MRI is the imaging modality with T2 weighted images being the MRI sequence for injuries and T1 weighted images the very best for serious injuries. MRI will show muscle stomach hematoma, and MRI can be used to confirm patients who can benefit from surgical therapy.

Management

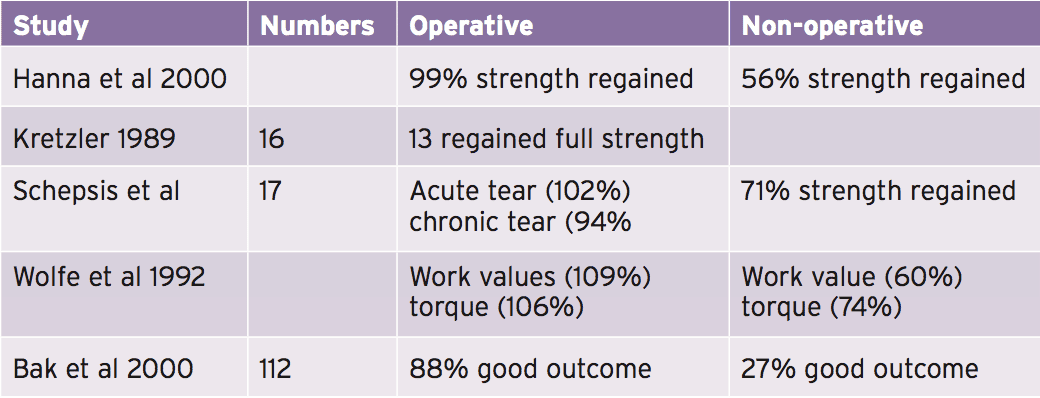

SurgeryHistorically, surgery is recommended in the athletic people and for those wanting to return to recreational pursuits. People who choose conservative management have been demonstrated to have reduced peak force creation and work ability when measured on isokinetic devices when compared to their other hand (Wolfe et al 1992 and Bak et al 2000). Tears of the muscle belly or distal partial tears in populations may enjoy a reasonable result if treated conservatively. Furthermore, it has been indicated (Zafra et al 2005) the longer the time between injury and repair makes the repair of the torn tendon harder, therefore early repair is advocated (within the first couple of weeks).

Surgery is done with a incision at the crease line that was deltopectoral. The tendon has to be examined with the arm and externally rotated as often the costo-sternal head tears will be concealed by the clavicular head if the arm is by the side. The full length of the thoracic and musculotendinous junction (MTJ) need to be assessed to determine exact site of the tear. MTJ injuries are fixed with sutures.

If the tendon has ruptured in the bone attachment then the lip of the bicipital groove is exposed and rid of tissue. Anchors and drill holes are used to re-attach the tendon. Typical tendon tears may need around four anchors.

Post-Surgery Rehabilitation

The arm is going to probably be rested in a sling for four to six weeks in a sling that is simple or within a sling immobilizer. It’s claimed that ruptures inside the soft tissue components (muscle, MTJ or inside the thoracic) may take longer periods of immobilization (6 months) compared with direct tendon into bone ruptures (four months). The reasoning for this is that direct tendon into bone attachment is much more secure than within soft tissue repairs. Manske and Prohaska 2007 provide removal of protocolsThe Main time dependent goals following repair are:

1. Maintain integrity of these soft tissues post-repair;

2. Restore full range of motion;

3. Restore muscle control and regain strength;

4. Return to full unrestricted participation.

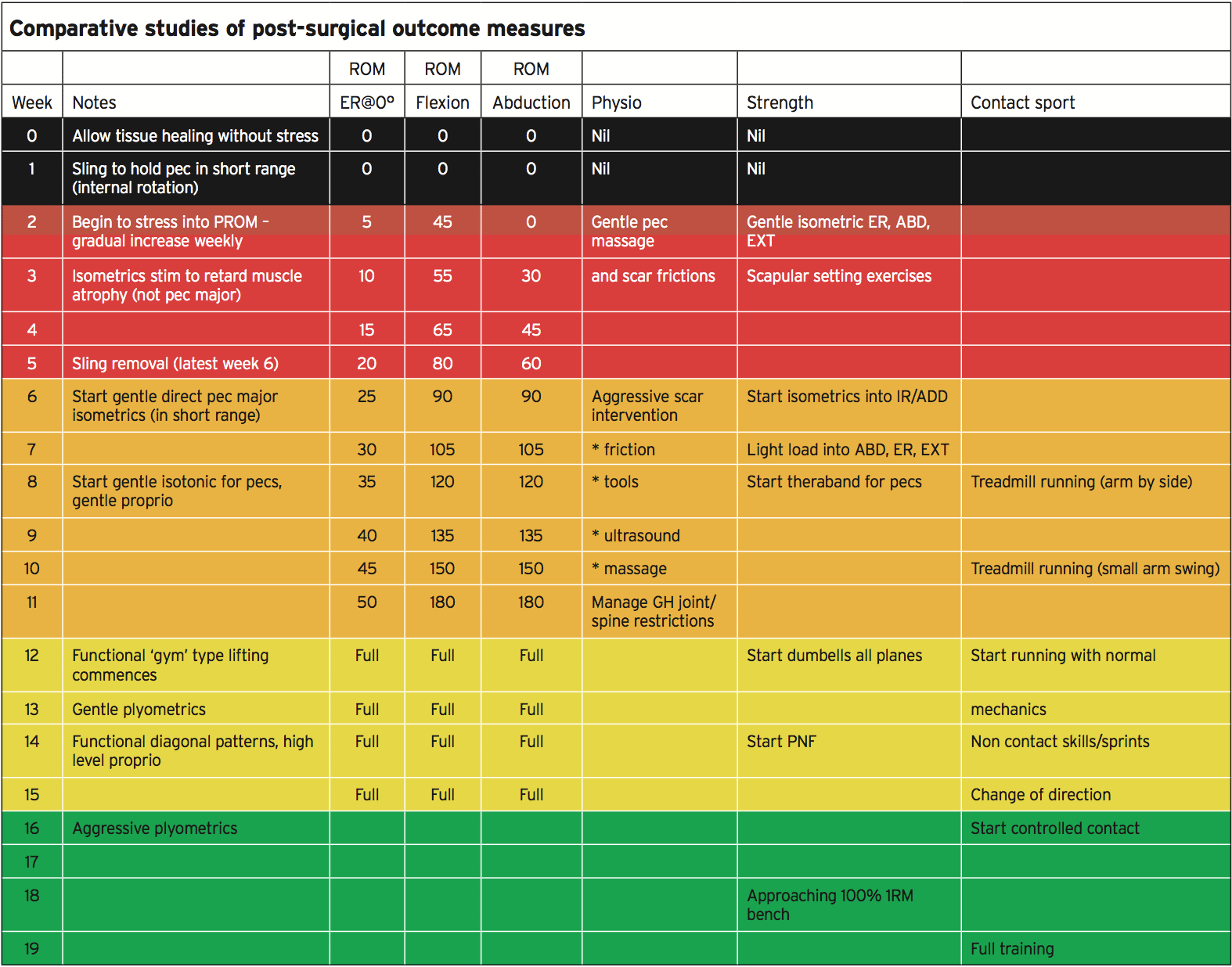

Range Of Movement Progressions

The main goal in the first stages (initial 3-4 weeks) is tissue protection to permit the sutured tendon fibers to gel and heal. The patient will be trapped in a sling and no passive or active movement is going to be allowed for the initial fourteen days. From week 3 onwards, gentle passive range of movement into external rotation (with the arm by the side), flexion and abduction. The permitted ranges at each point is shown in the table above (altered by Manske and Prohaska 2007).The passive array is slowly opened up to flexion, abduction and external rotation and they could be permitted to do this actively within resisted positions once the individual achieves movement for that week’s desired range. Initially the variety is therapist guided to prevent the danger that the patient ‘opens’ the shoulder up excessively. They can gradually and in a controlled fashion use that vary when the patient appreciates the range needed and they can be reliable. The aim would be to have full active/passive motion from the 12th post-operative week.

Physiotherapy Interventions (Progressions)

Since the surgical procedure does input the shoulder joint itself, the process is deemed extra-capsular shoulder joint effusion and adhesions aren’t present. Because the surgical technique does involve considerable excision of the soft tissue planes to access the ripped pectoralis tendon, adhesions are common from the fascia and surrounding tissue. Early and secure mobilization is encouraged to prevent adhesion formation that could result from complete immobilization. Gentle movement was proven to permit the scar tissues to cure planes of stress along and to promote collagen repair.Frictions and scar tissue massage and massage through the muscle can start to handle post- operative muscle tone and also to mobilize the scar tissue. This might be debilitating in the period due to post-surgical trauma this can also gradually become tooling using specialist metal massage tools ultrasound and more aggressive in the form of deep cross friction.

Soft tissue work to the pectoralis major can gradually be implemented as well as massage to all shoulder/ scapular muscles which may become shortened due to motion restriction — pectoralis minor, latissimus dorsi infraspinatus.

Since the range of movement improves, it could be essential for the therapist to also begin some direct glenohumeral joint accessory mobilizations (AP, PA(lateral extremities) for glenohumeral joint health. It could be necessary to mobilize the thoracic and cervical spines and the rib articulations as these can become restricted due to the premature immobility and tight.

At the subsequent stages as range and strength of motion have enhanced, the therapist is going to be required for the PNF repeat contractions that are hands on strength work.

Strength Progressions

Originally, no pectoralis major regeneration is allowed for the initial six weeks. This is to avoid any disturbance of the/ bone complex. However, additional muscles may be started for by isometrics provided that the arm is kept in the ‘safe’ range for this week. Scapular placing, shoulder abduction, extension, external rotation will keep tone from the shoulder muscles that are surrounding.From week 6 onwards, the individual may start isometric pectoralis major contractions in a shortened position and utilize muscle stimulators (initially in low contraction modes like atrophy mode). The strength of this contraction could be progressed. Scapular exercises can now be worked through all scapular ranges of upward/downward spinning, retraction and depression/elevation. Load may be increased for extension, abduction and the external rotation movements.

From week 8, gentle theraband exercises may start for pectoralis major for example flexion, adduction and rotation. From week 8 that the individual can also start gentle proprioceptive-type exercises which keep the arm in a secure range of motion. These might be easy reach- and-feel form drills which place consciousness.

From week 12, conventional dumb- based exercises may be started to implement gentle load to planes of movement. Before the end would be the sequence of strength recovery in conventional strength training that would safely enable adaptation in all of shoulder muscles and protect the major:

1. Horizontal pulling — rowing likely fly;

2. Horizontal pushing — shoulder press, dumbbell raises;

3. Vertical pulling — chin ups, pulldowns;

4. Horizontal pressing — bench press and each of the variations.

The restoration in strength in these directions will be variable it could be expected that full horizontal pushing strength that strategy levels that are pre-injury may take 20-24 weeks post-surgery to achieve and that starting at 50 percent of 1RM levels would be secure. However, high load pectoralis exercises beneath long levers must be prevented for six months (pec drops, fly’s).

Additionally at week 12, the patient will have to begin innovative proprioceptive-type shoulder exercises. These can include holding positions on balls and alphabet .

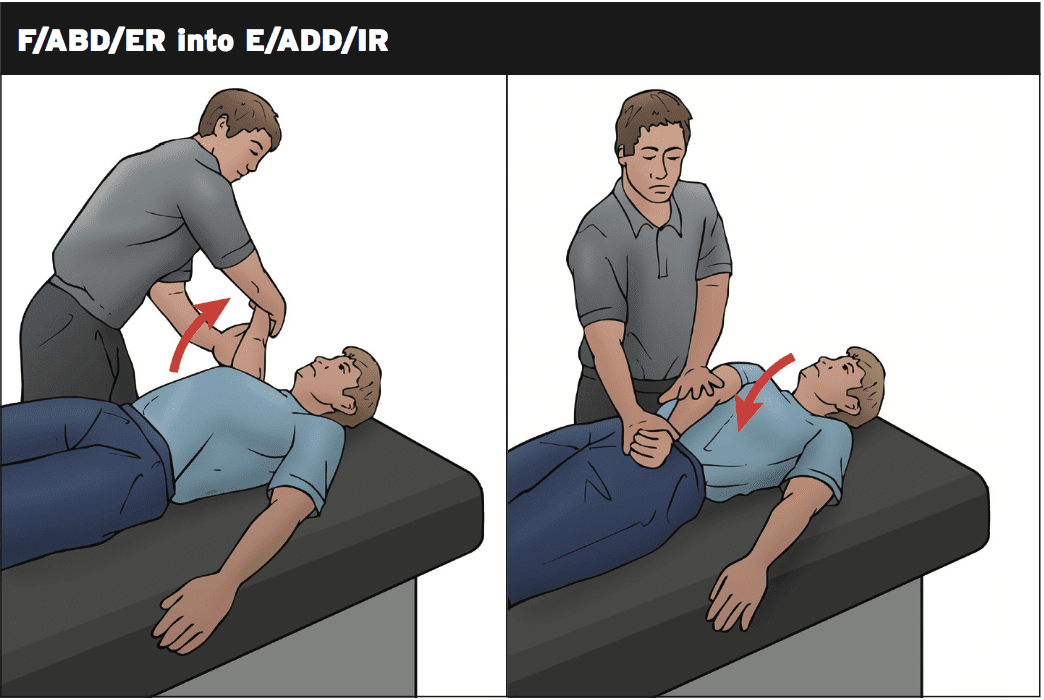

PNF repeat contractions may begin from week 14 so long as the patient has movement to abduction.

These progress by week 18 to maximum resistance and can begin with therapist resistance.

The PNF pattern starts with the patients arm in flexion/abduction/external rotation. The therapist applies pressure in the patients hands and on the arm. The patient then contracts to adduction and internal rotation. This motion is softly resisted from the therapist. The application that is common is just three sets of 10 contractions. Their resistance that is guide cans boost.

Cross-Training

Such as bicycle, water running together with the arm may begin at the early phases.Cardio movements which require arm movement in the below 90 degrees type shoulder airplane (rowing ergometer, cross trainer, jogging ) can commence around week 10.

More direct arm cardio exercises like grinder (week 12), swimming (week 14), boxing (week 16) would be postponed until the end.

Return To Sport

This stage will be dependent on the type of sport played however, as the majority of the team sport-related pectoralis ruptures are observed in the sports, then this may be used to describe return.The to implement return to sport features are:

1. Week 8 — treadmill jogging (arm in a secure posture)

2. Week 10 — treadmill running (short arm swing).

3. Week 12 — unrestricted field running (not sprints)

4. Week 14 — non contact catch/pass drills and sprinting

5. Week 16 — start controlled contact training (4 weeks development)

6. Week 20-24 — return to play if all other objectives fulfilled.

Post-Surgical Outcome Measures

Testing is usually involved by normal lab evaluations for your pectoralis major on KinCom or even Cybex. The set-up for these tests is to have the patient supine lying with the shoulder beginning in 160-degree abduction and forward flexion that is 30-degree. The arm is then moved into comparative extension, internal rotation and adduction to the hip. Movement’s arc is 140 degrees and is performed at a rate of 120 degrees per minute.A lot of studies are conducted that assesses operative results. The findings – rise and the decisions are that the vast majority of patients return to full function post-surgery.

Conclusion

Ruptures of the pectoralis major are injuries they do occur in sports such as bench skiing, wrestling, rugby and pressing. The majority of ruptures that are complete and incomplete will need surgery to establish congruency within tendon fibers or even the bone attachment.Return to game and Rehabilitation typically takes 4-6 weeks for the athletic population. The rehab involves restoring array of strength, motion and function and is comprehensive.

References

1. Bak et al (2000) Rupture of the pectoralis major: a meta-analysis of 112 cases. Knee Surg Sports Traum Arthro. 8: 113-119.

2. Hanna et al (2001) Pectoralis major tears: comparison of surgical and conservative treatment. Br J of Sp Medicine. 35: 201-206.

3. Kakwani et al (2007) Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle: surgical treatment in athletes. International Orthopaedics. 31; 159-163.

4. Kannus P and Jozsa L (1991) Histopathological changes preceding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J of Bone and Joint Surgery 73A.

5. Kretzler HH and Richardson AB (1989) Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J of Sports Med. 17; 453-458.

6. Manske R and Prohaska D (2007) Pectoralis major tendon repair and post surgical rehabilitation. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2(1); 22-33.

7. Marmor et al (1961) Pectoralis major muscle: function of sternal portion and mechanism of rupture in normal muscle. Case reports. J Bone and Joint Surgery (A): 43; 81-87.

8. Merolla et al (2012) Pectoralis major tendon rupture. Surgical procedures review. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2(2); 96-103.

9. Provencher et al (2010) Injuries to the pectoralis major muscle. Diagnosis and treatment. Am J of Sports Med. 38(8): 1693-1705

10. Schepsis et al (2000) Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Outcome after repair of acute and chronic injuries. Am J of Sports Med. 28; 9-15.

11. Tietjen R (1980) Closed injuries of the pectoralis major muscle. J Trauma. 20; 262-264.

12. Wolfe et al (1992) Ruptures of the pectoralis major muscle. An anatomic and clinical analysis. Am J of Sports Medicine. 20; 587-593.

13. Zafra et l (2005) Chronic rupture of the pectoralis major muscle: report of two cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 71; 107-110.