Running is possibly the most fundamental of sports, but it is still bothered with a plethora of lower limb injuries. Here injury scientist Dr. Alexander Jimenez focuses on the relationship of running biomechanics and related injuries to the hip joint, the greatest and most complicated of the lower limb, with a few preventative techniques to incorporate into your own training.

Hip Runners & Problems

Hip pain is not the most common injury as it frequently does not occur instantaneously, but is that the accumulation of training and manifests as a gradual worsening of symptoms. The injury rate for long distance runners is approximately 3.3%-11.5% (1) and the hip is supposed to contribute to up to 14 percent of athletic injuries (two). Given the diversity of athletics, the hip is placed by this since the offender of nearly a sixth of injuries sustained. The intricacy of the hip joint leaves about 30% of hip pains undiagnosed and treatment plans cannot target the issue. Reoccurrence or impairment that is on-going then result from not fixing the cause.Hip Anatomy

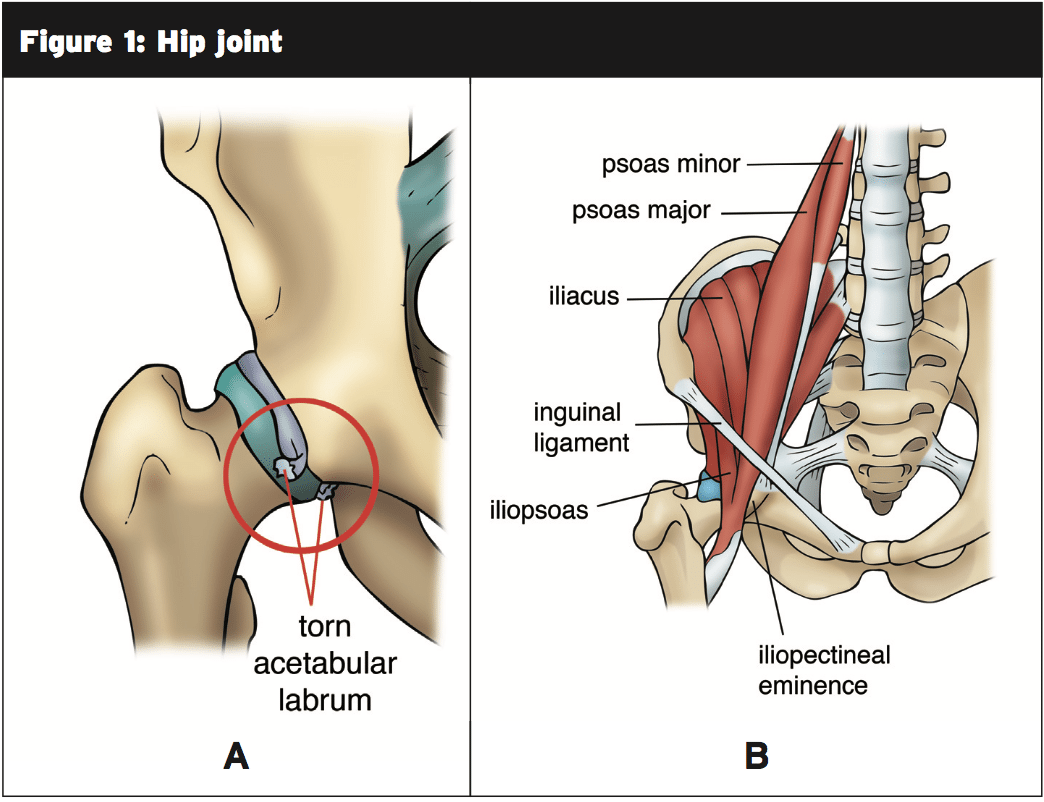

Fig. 1: a) The hip joint displaying the femoral head connecting to the acetabulum; a tear into the labrum is comprehensive; b) The hip joint and pelvis with surrounding muscles shown (5).This architecture makes it possible for the cool to move in all 3 planes (forwards and backward, to both sides, and to rotate inwards and outwards) providing six different moves and therefore a very flexible joint (4). This mobility is what if coupled with the speed and power of running and produces the hip complex in character, allows an array of complications.

Biomechanics Of Running

Of running, the cycle can be broken down into two stages to help clarify effect is transported through the mechanics of running occur and the body. Both stages would be the stance phase (when the foot lands on the floor), displayed along the bottom in Figure 2, along with the swing phase (when the foot is moving through the atmosphere).The lower limb muscles at the hip, shoulder and knee all work to restrain movements and to limit the forces. They encounter floor reaction forces from the power of the muscles contracting and the impact of the floor. The thicker the stance phase, eg the larger or the tougher that the landing the operate, the more activation required with these muscles to offload the joints and also consume these forces.

Whilst each runner will have a style, the repetitive routine of conducting and its impact can exceed a runner’s limitation on the strain they can endure. This combination of variables is the reason behind injury.

The Impacts Of Running On The Hip

In conducting, the effect occurs through the heel strike. The amount of this will depend on the frequency the duration of contact, and also just how heavy you land on the heel. Runners who impact more will have less effect force. A single load can damage the articular cartilage and rip the labrum, particularly if associated with a sudden trip or fall. More likely, however, it’s the repetitive loading from running that causes small micro injury to the hip joint, and this accumulation of harm will eventually thin the cartilage layer resulting in tearing and shearing of these cells (4).The fashionable flexes to absorb these impact forces through the hip flexor muscles of Pectineus, Tensor Fasciae Latae, and Ilioposoas, Sartorious, Rectus Femoris. The pelvis will rotate backward to allow more space to happen to flexion. It is going to then marginally adduct (using adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus and pectineus) prior to moving into abduction (using the gluteus medius primarily) to your terminal swing and remove (7). The hip motions into extension (the leg goes backward) to propel the body forward and this mostly exerts the gluteus maximus muscle while the pelvis tilts forward to adapt the hip joint mechanics. If some of those mechanical motions become compromised the forces will be transmitted incorrectly, giving instability and putting increased strain into muscles and the hip joint. Repetitive loading subsequently leads to trauma.

Hip Pathologies & Their Relation To Running

There’s a multitude of hip pathologies the runner may endure. Here we will have a look at the most common injuries.Strains — Strain can occur to any of those muscles involved with hip biomechanics if they’re overloaded from poor alignment and mechanisms. The muscle strains happen into the iliopsoas from over-flexing in the hip joint, or on impact once the hip is still flexed and load is taken by the muscles. The gluteus medius can also become injured if the runner over-adducts (where the hip moves inwards) during their running routine and the gluteus medius tendons get irritated with direct compression below the bone.

Trochanteric bursitis — This can be swelling and inflammation of the fluid-filled sac that’s the bursa that resides to the greater trochanter (the other side of the hip). This bursa normally allows movement of the band over the hip bone, but repetitive shearing may cause it to become inflamed.

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) — This occurs when the femur induces impingement on the acetabulum, mainly when the cool comes into flexion as well as the bony structures collide. This may occur as a pincer impingement as a CAM impingement where an extra ridge of bone develops , or where the acetabulum rim develops an lip of bone. As the labrum is ground back on by the extra bone repeatedly FAI which goes unresolved can finally lead to tears.

Labral tear — This is currently tearing of the labrum that surround the hip joint and acetabulum. It may happen over time by or out of a traumatic event micro – traumas.

Analysis and the assessment of those pathologies is beyond the scope of this article; however, a physiotherapist may use testing to assist with diagnosis and therapy planning.

Rehabilitation & Prevention Guidelines

Given this variety of pathologies that are potential, a identification is imperative for therapy planning. The therapy suggestions below could be applied from hip injury, or for rehab to the avid runner for measures.Information regarding the avoidance of repeated or regular hip flexion should be paramount. This will the anterior hip and replicate type problems to impingement. If flexion cannot be averted, ie with sitting, then the runner should be educated to lean back or stand up into extension. Cycling and treadmill running wouldn’t be proper cross-training methods as both encourage hip flexion and internal rotation (giving more impingement to the acetabulum)(7). Swimming is non-impact and avoids these positions that are irritable. The three phases of rehabilitation joint with preventative measures or could be followed in order:

1. Strengthen the gluteal muscles the gluteus medius and maximus in isolation;

1a. Bridging

Lie on your back with your knees bent and arms. Put a resistance band around your thighs so that it pulls on your knees. You need to make an effort to maintain them apart from pushing against the band (this activates gluteus medius). Slowly push up through the heels and lift your buttocks and back off the floor, holding for five minutes and then gradually returning (since the knees remain bent the hamstrings can’t control and gluteus maximus is going to be triggered). Duplicate for collections.

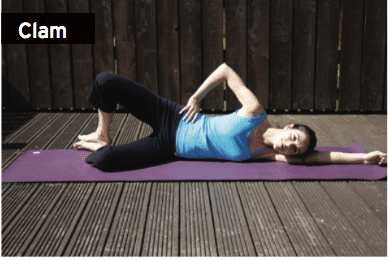

1b. Clam

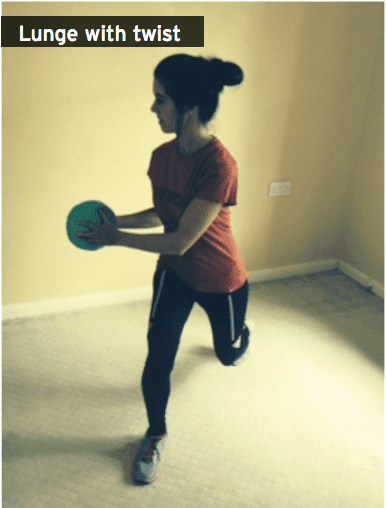

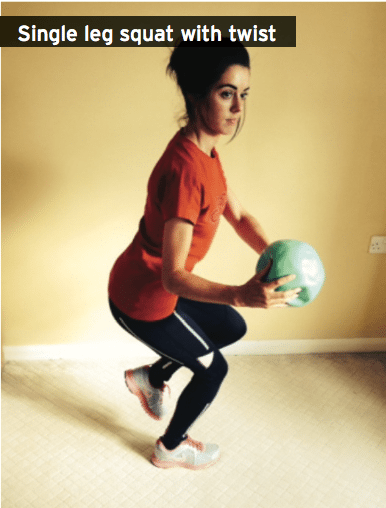

2. Strengthen the whole limb with joint movements incorporating muscle groups and core stability;

2a. Lunge with twist

2b. Single leg squat

3. Strengthen the fashionable in movements that replicate running patterns;

3a. Standing hip hikes

Stand erect with feet hip distance apart. Hitch up the specified hip while maintaining neutral pelvic stability (eg do not let your hips twist or move . Repeat for three sets of 10 repetitions.

3b. Forward step-ups

Stand in front of a high step or stair and hold on to a banister or rod at the same side (pushing down this will activate the latissimus dorsi back muscles which are associated with the gluteal muscles. Leading with the chosen hip step upwards then return back down. Repeat leading with the leg every time for three sets of 10 repetitions.

3c. Hip swings

Return To Running Program

Return to running injury can happen together with the strength training when the problem was corrected, muscular strength and control is adequate and biomechanics are adjusted. The runner should aim to begin with these guidelines at approximately 60 per cent intensity and duration of runs and advancement:- Begin working on soft surfaces to restrict impact eg monitor or ground;

- Include a comprehensive dynamic warm-up

- Increase rate once technique is adequate;

- Run on alternate days for the first 3-4 weeks;

- Continue with strength training above and expand to build workout and strength whilst minimizing impact;

- Slowly introduce sprints, hills, accelerations, decelerations; picking one element at a time (7).

Overview

- Because hip flexibility and strength is vital for every single stride, hip injuries can be painful to the runner. The hip joint is a complex joint that goes in several directions and can be stabilized with a profound acetabulum and muscles and ligaments;

- These muscles control the fashionable orientation of running at every stage. The stance phase and swing phase require muscles to operate at different times;

- The hip can endure injuries from running such as femeroacetabular impingement, bursitis, muscle strains and tears;

- These injuries are the result of biomechanics, giving pelvic uncertainty that forces are transmitted 25, and changing the lower limb alignment and overload the structures;

- Rehabilitation and/or prevention exercises should be included consisting of functional running-related exercises limb strengthening and strengthening.

1. Br J of Sports Medicine. 2007; 41(8), 469-480.

2. J of Orthop and Sports Phy Ther. 1994; 19, 121-129.

3. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008; Jan 466(1): 239-247.

4. Phys Ther in Sport. 2004; 5: 17-25.

5. Brukner P and Khan K (2009). Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd ed. Australia: McGraw-Hill Professional. 48-49.

6. J Biomech. 1993; Aug 26(8): 969-990.

7. Phys Ther in Sport. 2014; Article in Press:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. ptsp.2014.02.004.