Sudden cardiac death in athletes is rare. Yet, recent evidence indicates that cardiac screening that is proper might lessen the risk of death even farther. Scientific specialist Dr. Alexander Jimenez explains…

On 17 March 2012, the Bolton footballer Fabrice Muamba failed during the first half of an FA Cup quarter-final match between Bolton and Tottenham Hotspur at White Hart Lane — he had suffered a cardiac arrest. Muamba received extended medical focus about the pitch, which included assistance from a consultant cardiologist who (fortunately) only happened to be present as a spectator that day. His heart had stopped for 78 minutes, although during the course of his crisis therapy, Muamba received numerous defibrillator shocks both and at the ambulance. After additional treatment at a specialist care unit, Muamba was discharged from hospital less than a month later where he expressed his gratitude, and he managed to attend Bolton’s home game against Tottenham Hotspur on 2 May.

Despite the happy ending to the story athletes who undergo a sudden event aren’t so blessed. And although the true incidence of sudden death in any sort of athlete is very rare (ranging between 1 in 50,000 [Italian statistics] and 1 in 200,000 [US figures(1)]), the psychological impact on society is elevated — not least because sportsmen and women are seen as the weakest segment of the populace. It is this contrast that fuels the debate about the best approach in order to identify people at risk.

Causes Of Sudden Cardiac Death

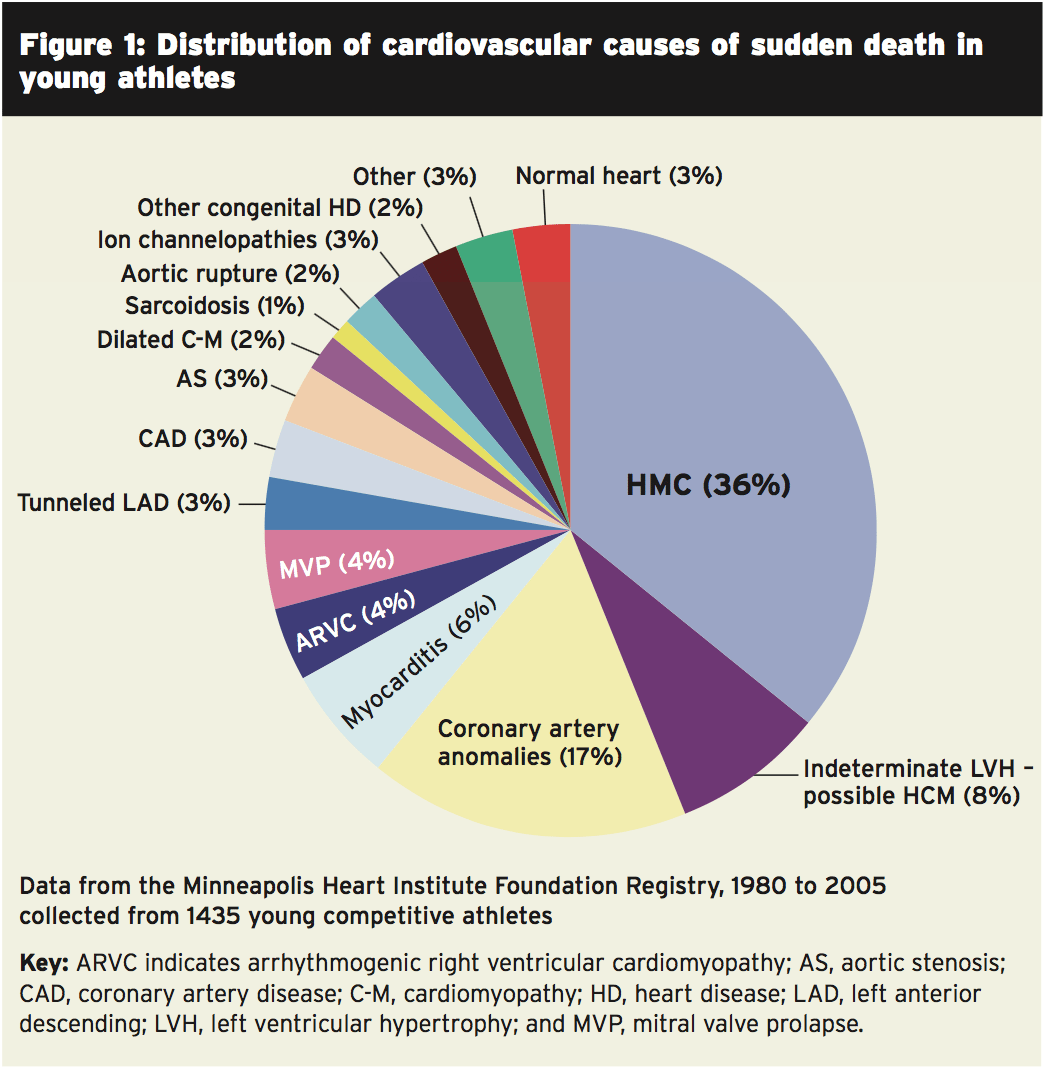

Evidence from the US suggests that the vast majority of sudden deaths in athletes under 35 years old are due to many congenital or acquired cardiac malformations (see Figure 1, which shows some representative data for sudden death causes due to a cardiac event in young athletes)(2). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is a primary disease of the myocardium (heart muscle) where a part of the myocardium is hypertrophied (thickened) with no obvious trigger and is the single most frequent source of athlete deaths (in charge of about one- third of the cases).Athletes that train frequently manifest changes in their own heart muscle in the same way they show changes in their other muscles; the heart becomes bigger and the walls across the left ventricle become thinner. The volume within the left ventricle increases and the heart becomes more efficient at pumping blood to the rest of the human body.

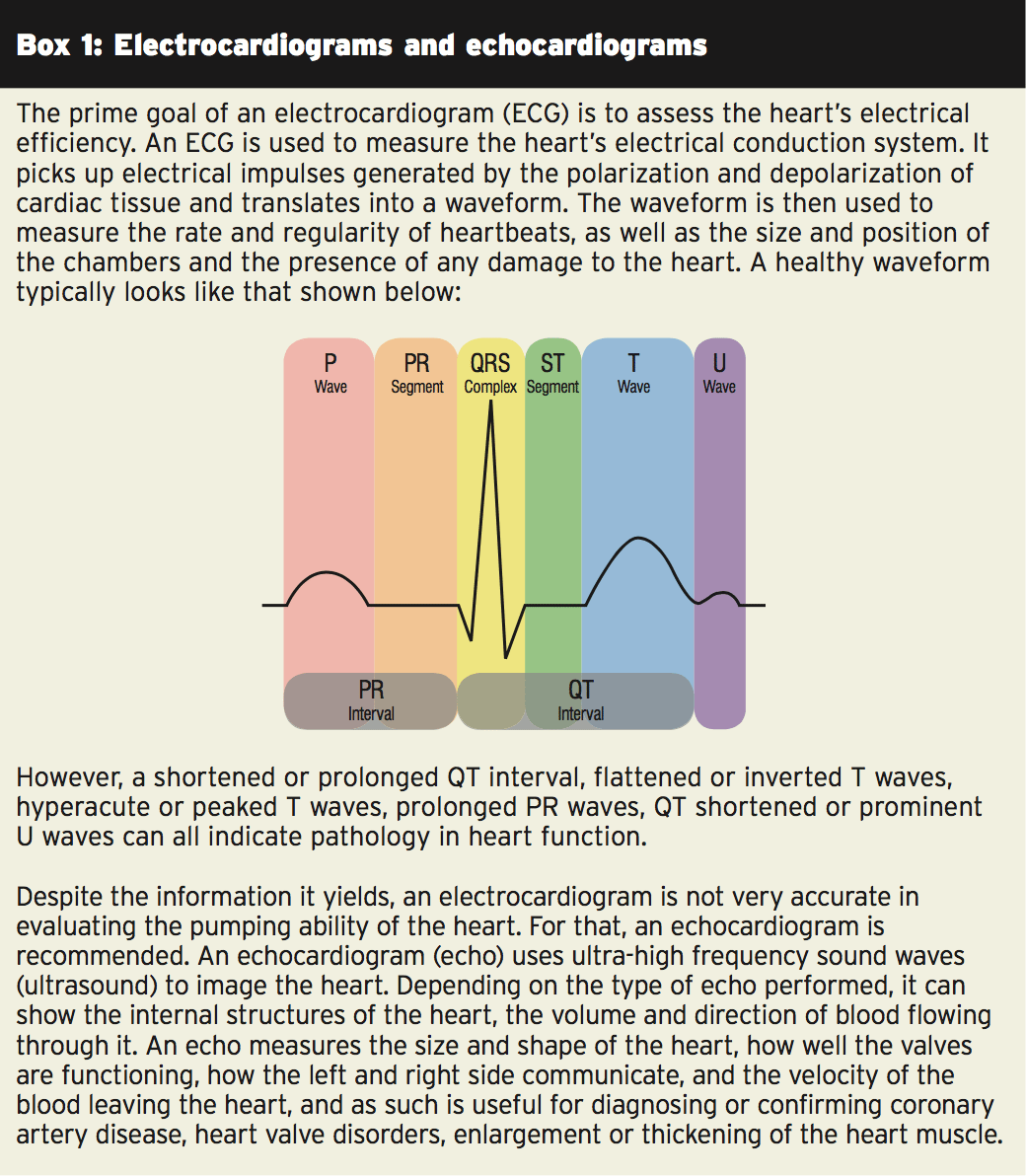

While the true heart function remains normal in athletes that experience these physiological changes, they may result in what would be considered ‘unnatural’ electrocardiogram (ECG) readings(3). It is extremely important, therefore, for sport doctors to have the ability to differentiate between normal (and healthy) hyper- trophic changes in the heart tissue of an athlete and pathological changes — for instance, those caused by abnormal heart rhythms.

It’s still possible for sudden death to happen as a consequence of an electrical malfunction, where absolutely no structural changes in the center exist. This is particularly challenging for physicians trying to screen athletes for cardiac risk because in such instances, a cardiac arrest may be the first sign that something isn’t right. Trainers with arrhythmias that were known, on the other hand, can be managed with drugs and may be candidates for an implantable cardioverter defibrillator, a type of pacemaker that automatically finds arrhythmias and shocks the heart back to normal sinus rhythm.

Screening & Prevention

What is the best approach to prevent cases of sudden cardiac death among athletes? This is a continuing subject of debate. A pre-participation health evaluation is recommended by the European Society of Cardiology and the International Olympic Committee for athletes, which includes a family and personal history, a physical examination, along with also a 12-lead ECG to examine heart rhythms. In the United States, however, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends only the history and physical portion of the examination (see Table 1), together with referral to more testing only for those with significant risk factors. In Europe, different states apply different regulations regarding the minimum complementary tests which needs to be used in competitive athletes, ranging from ECG to exercise testing or mandatory echocardiography (see Box 1).ECG & Echocardiography

The debate on the appropriate screening techniques to identify athletes at risk of sudden cardiac death is ongoing, especially as there is currently no universally approved screening protocol. In 2008, US researchers investigated the use of EGC and echocardiography screening to detect the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in highly trained athletes(4). Between 1996 and 2006, 3,500 asymptomatic elite athletes (75 percent male/25% female) with a mean age of 20 years underwent 12-lead electrocardiography and two-dimensional echocardiography. None of the athletes had a family history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.Of the 3,500 athletes, 53 (1.5 percent) had left ventricular hypertrophy, and of those 50 had a dilated left ventricular cavity with normal diastolic function to signify physiological left ventricular hyper- decoration. Three athletes with ventricular hypertrophy had a left ventricular cavity and associated. But, none of those athletes had some phenotypic characteristics of HCM on non- invasive testing and none had relatives with features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. One of these three athletes agreed to detrain for 12 weeks, which demonstrated resolution of electrocardiography and echocardiographic changes confirming physiologic (non-pathological) left ventricular hypertrophy.

The authors concluded that the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in highly trained athletes, overall is extremely rare and that changes associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have a tendency to pick out individuals from sports. They also concluded that viewing athletes with echocardiography was not cost effective but that electrocardiography was in selecting out those individuals who may have had left ventricular hypertrophy for echocardiography useful.

Further support for the use of ECG screening comes out of a 2012 inspection analysis, which analyzed the issue of pre- participation screening for the detection of intrinsic structural or electrical cardiovascular disorders that predispose an athlete to sudden cardiac death(5). It concluded that there was significant evidence indicating that viewing athletes can’t therefore achieve the objective of screening and with just a history and physical evaluation renders athletes with a serious underlying cardiovascular disease undetected. The authors included: “Pre-participating cardiovascular screening inclusive of an ECG significantly enhances the ability to identify athletes at risk also is the only model demonstrated to be more economical, and might reduce the rate of sudden cardiac death.”

Though ECG screening demands a medical workforce skilled in interpretation of an athlete’s ECG latest studies have shown that this technique is able to distinguish normal physiological ECG alterations in athletes from findings suggestive of an underlying pathology and this may be achieved using a reduced false-positive rate(4). You might think that ECG screening is the approach that is preferred but also in itself adequate for detecting pathologies. However recent research indicates that echocardiography can be an extremely valuable tool, especially when coupled with ECG data.

A ‘Focused’ Strategy

A study published earlier this year appeared at early screening for cardiovascular abnormalities using a technique known as pre- involvement ‘focused echocardiography"(6). Focused echocardiography uses a miniaturized and portable echocardiography system, which allows the trained operator (that doesn’t need to be a technical cardiac physician) to quickly evaluate key facets of cardiac function including pericardial effusion, chamber size, international cardiac function, left ventricle size and ventricular function. The researchers wanted to learn if using reduce referrals concentrated echocardiography could enhance rates, and broaden the spectrum of disease which could be captured through screening of athletes.Sixty-five male collegiate athletes (aged 18 to 25 years) have been screened with a history and physical examination, ECG, and focused echocardiography performed by a non-cardiologist sports medicine physician. The history and physical examination were based on the 12-element American Heart Association recommendations (Table 1) and the 2010 European Society of Cardiology standards were utilized to interpret the ECG data. Specifically, the (physician-operated) focused echocardiography was performed to search for hyper- trophic cardiomyopathy and aortic root dilatation. Athletes were referred to a cardiologist.

The majority of the athletes (59) did not screen positive by any screening modality. Three athletes screened positive but had focused that was regular echocardiographic findings. Three athletes screened positive but had normal ECG and concentrated findings. All athletes finally cleared for sports participation and were referred to a cardiologist. Significantly, no athlete screened convinced by concentrated echocardiography. The end was that focused got measurements similar to those of proper echocardiography and echocardiography was able to decrease the referral rate for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The simple fact that concentrated portable machinery that may be operated by a non-cardiac specialist is utilized by echocardiography suggests potential for effective and rapid screening in the specialty.

The Bigger Picture

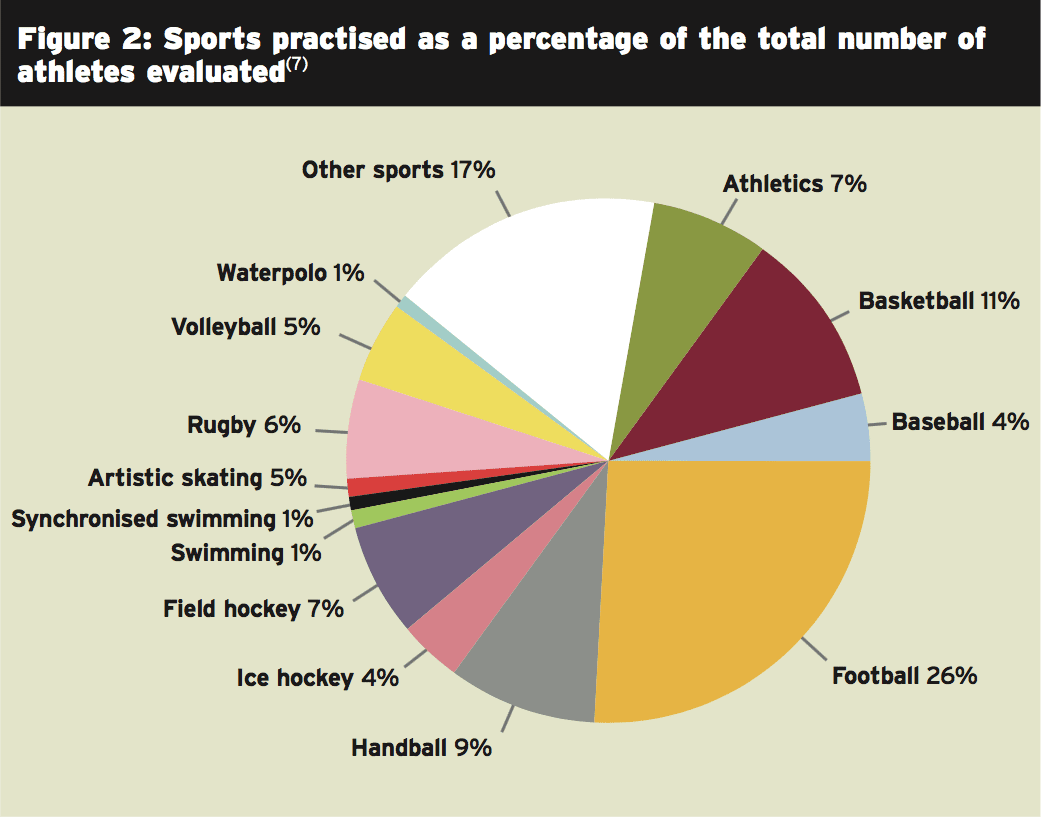

The study above used a small sample of subjects, and sports physicians might assert that findings in studies are needed to demonstrate its value. As it happens, a newly-published Spanish research offers strong evidence for the advantages of echocardiographic screening(7). Within this analysis, engaging in game and 2688 athletes in various sporting disciplines were analyzed to December 2013.Of the athletes 67% were men and feminine, and the mean age was 21 years. In the time of the study, 164 of those 2688 athletes studied (6.1 percent) were specialists. The majority of the study population (79.6%) competed in regional contests, whereas 357 (13.2 percent) and 192 (7.2 percent) competed in domestic and international events, respectively. The sport practiced by the athletes have been shown in Figure 2.

- Family and personal history

- Physical evaluation

- ECG

- Echocardiogram

- Maximum exercise testing

In terms of the findings, the majority of the echocardiography examinations (92.5 percent) were normal and showed no coronary disease; in 203 participants (7.5%), changes were seen in the echocardiogram. The change most often found was left ventricular hypertrophy: 50 athletes (1.86 percent) were discovered to have left ventricular hypertrophy, employing an interventricular septum cut-off of 12 mm. The incidence has been reduced to 30 (1.11 percent) if the cut-off was raised to 13 mm. Thus, 20 participants revealed left ventricular hypertrophy which may be considered “physiological”; however, not one of the ECGs of these athletes met the diagnostic criteria of hypertrophic heart muscle disorder.

Cessation of sporting activity was indicated in four athletes (0.14% of the research population). Two of those four athletes had hypertrophic heart disorder; in among these athletes, the ECG showed nonspecific changes (negative T waves at the left wall) which failed to fulfill diagnostic criteria. The next person had. The person revealed major pulmonary valve stenosis.

The key point to make here is that the addition of echocardiography to pre-participation screening was helpful because it supplied a broader evaluation of their cardiac threat than ECG screening independently, and enabled the identification of four athletes with threat of sudden death and three athletes with a disease that required a specific treatment or follow-up. Not one of these problems were discovered via medical history, physical examination, or ECG. Although the 0.14 percent of the study population is of low incidence, the consequences of being in a position to prevent four cases of sudden death or the abrupt development of cardiac disease from the athletic context clearly demonstrates the importance and value of incorporating echocardiography into pre-participation screening.

Conclusion & Recommendations

Even though there are time and cost issues, there is no doubt that pre-participation screening is an essential requirement in order to reduce the possibility of sudden death among athletes. At the minimum, this needs to include personal and family history using a physical examination. The evidence suggests that this sort of screening alone is inadequate to detect some kinds of serious cardiac disorder and that athletes participated in sport should also undergo ECG testing.Slightly more contentious is the use of echocardiography in the screening procedure. Even though it is not suitable as a manner of screening, the latest evidence indicates that coupled with an evaluation family/personal background and ECG information, it’s a valuable addition to the sports physician’s armory. Specifically, using focussed echocardiography directed at excluding specific ailments that cause difficulties for athletes (such as hypertrophic heart muscle disease, anomalous roots of the coronary arteries, mitral valve prolapse, and right ventricular dysplasia etc) appears entirely appropriate — particularly as this type of echocardiography doesn’t need to be carried out in a hospital setting by a skilled radiographer.

References

1. Heart. 2009;95:1409-1414

2. Circulation. 2007; 115: 1643-1655

3. Circulation. 2010;121:1066-1068

4. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008 Mar 11;51(10):1033-9

5. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2012 MarApr;54(5):445-50

6. J Ultrasound Med. 2014 Feb;33(2):307-13

7. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2014 Apr 8. pii: S0300-8932(14)00101-8