Chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez reviews the clinical presentation and assessment of quadriceps strains, along with a discussion of appropriate imaging used in diagnosis.

Strains and contusions of the quadriceps are common in sport and frequently result in lost time from training and competition. Acute strain injuries of the quadriceps commonly occur in sports such as soccer, rugby, and football, all of which require sudden forceful eccentric contraction of the quadriceps during regulation of knee flexion and hip extension. They are also known to occur in other sports involving sprinting such as track athletics.

A study published just two months ago provides a revealing insight into the incidence of quadriceps strain in sport. In this study, researchers examined the rates and patterns of quadriceps strains in student-athletes in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA)(1). Data was gathered from college students participating in 25 sports during the period 2009-2015. The key findings were as follows:

The four bellies converge distally to form the thick quadriceps tendon, which inserts into the superior pole of the patella. This tendon is composed of multiple laminae positioned one on top of the other. The superficial lamina is continuous with the muscle fibres of the RF. The intermediate lamina receives the fibres of the VM and VL, and the deepest lamina receives the fibres of the VI. A smaller percentage of fibres of the superficial lamina lie superficial to the patella and merge directly into the patellar tendon.

Strains and contusions of the quadriceps are common in sport and frequently result in lost time from training and competition. Acute strain injuries of the quadriceps commonly occur in sports such as soccer, rugby, and football, all of which require sudden forceful eccentric contraction of the quadriceps during regulation of knee flexion and hip extension. They are also known to occur in other sports involving sprinting such as track athletics.

A study published just two months ago provides a revealing insight into the incidence of quadriceps strain in sport. In this study, researchers examined the rates and patterns of quadriceps strains in student-athletes in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA)(1). Data was gathered from college students participating in 25 sports during the period 2009-2015. The key findings were as follows:

- The overall quadriceps injury rate was 1.07 per 10,000 athlete-exposures (AEs).

- The sports with the highest overall quadriceps strain rates were women’s soccer (5.67/10,000 AEs), men’s soccer (2.52/10,000 AEs), women’s indoor track (2.24/10,000 AEs), and women’s softball (2.12/10,000 AEs).

- Across sex-comparable sports, women had a higher rate of quadriceps strains than men overall (1.97 versus 0.65/10,000 AEs).

- The majority of quadriceps strains were sustained during practice (77.8%) but quadriceps strain rate was higher during competition than during practice.

- Most quadriceps strains occurred in the preseason (57.8%), and rates were higher during the preseason compared with the regular season.

- Most of the injuries were non-contact injuries (63.2%), while overuse injuries accounted for 21.9% of the total.

Quadriceps Anatomy

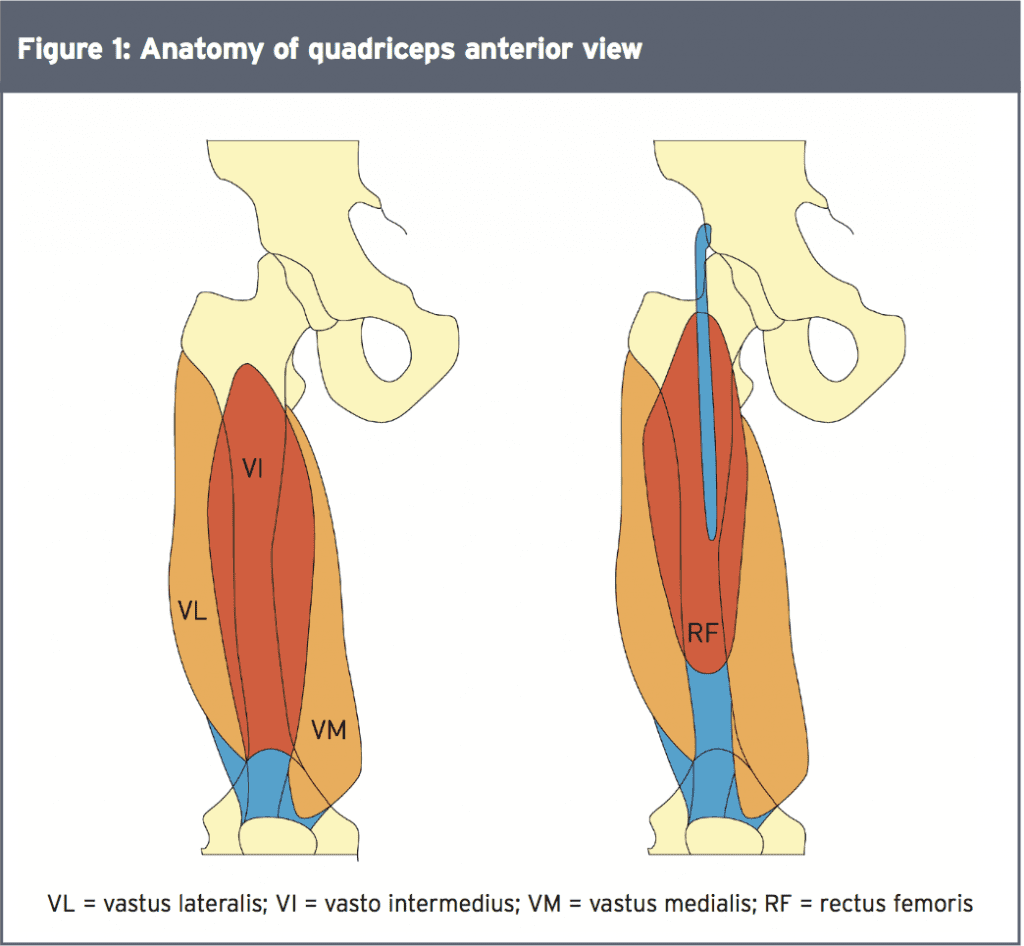

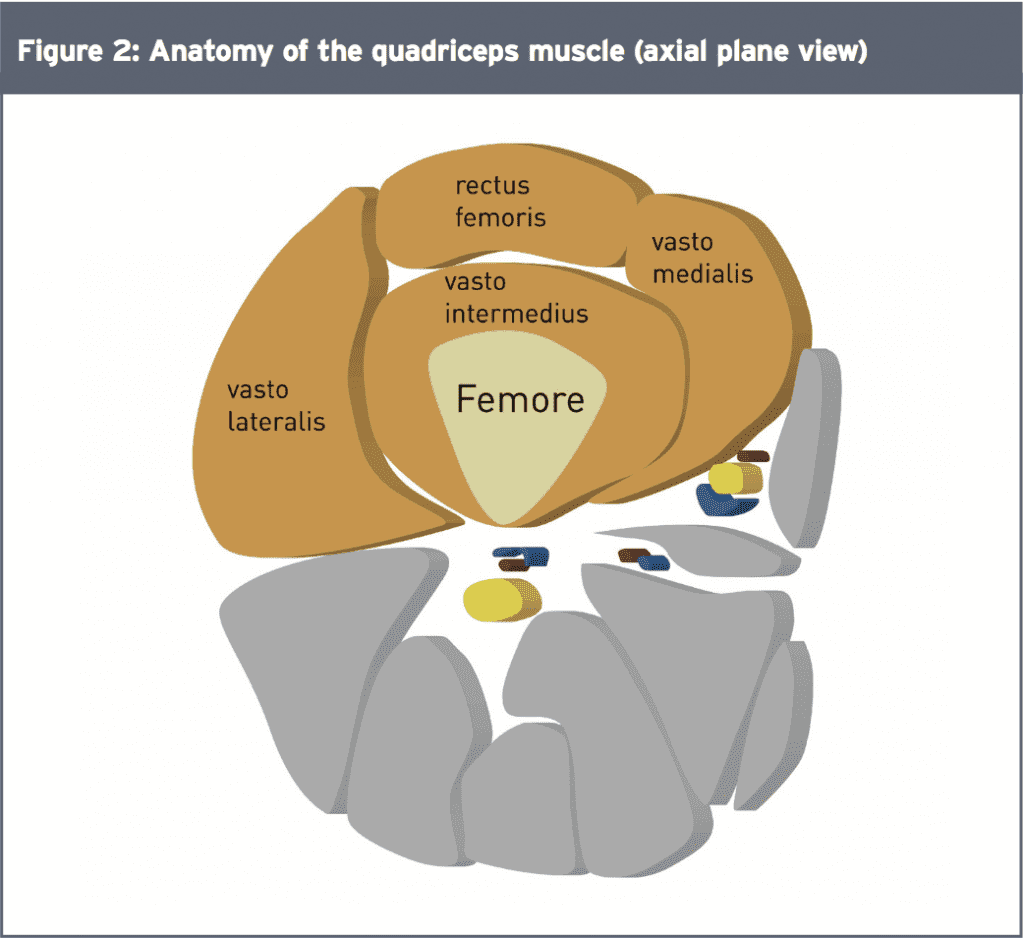

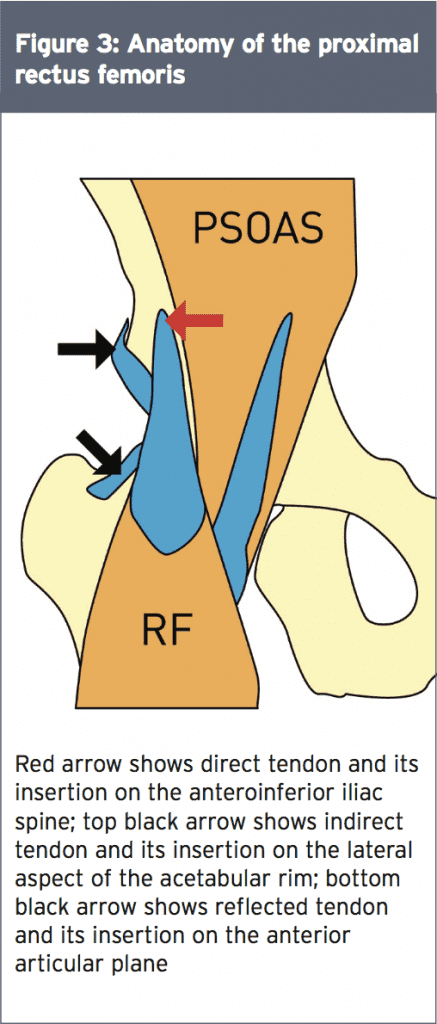

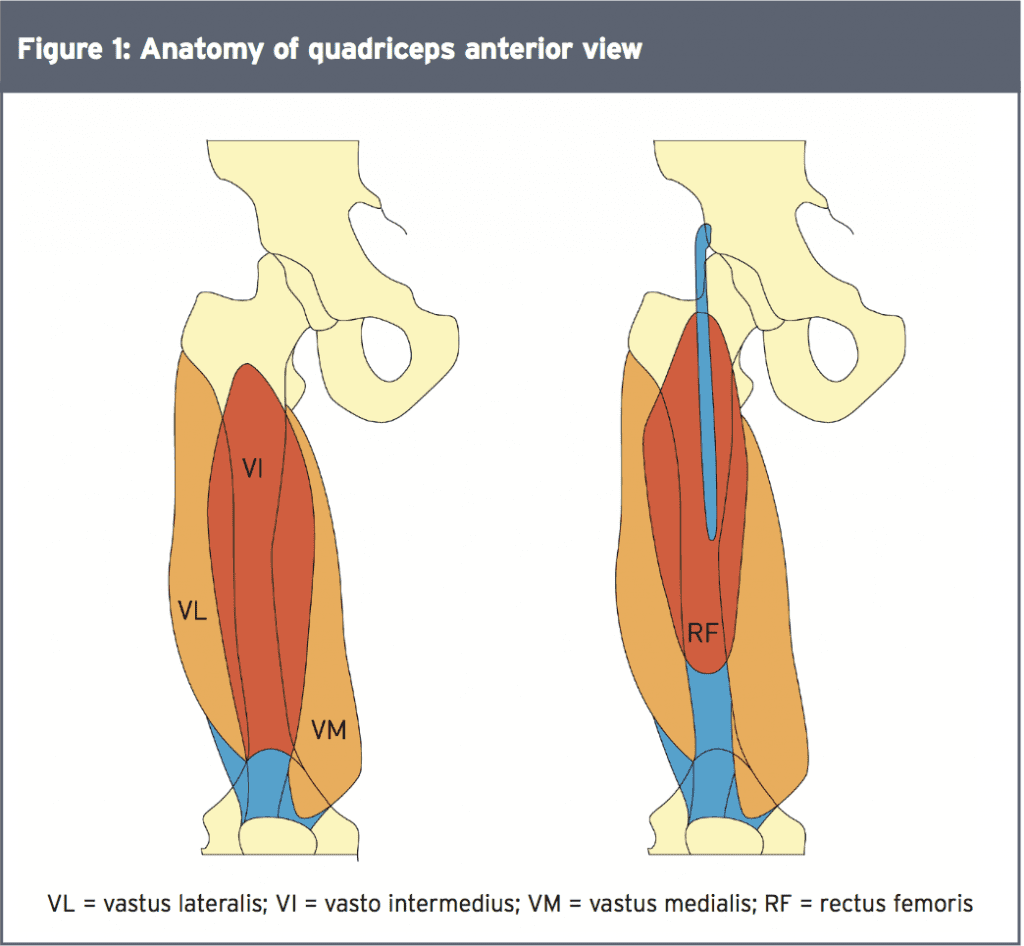

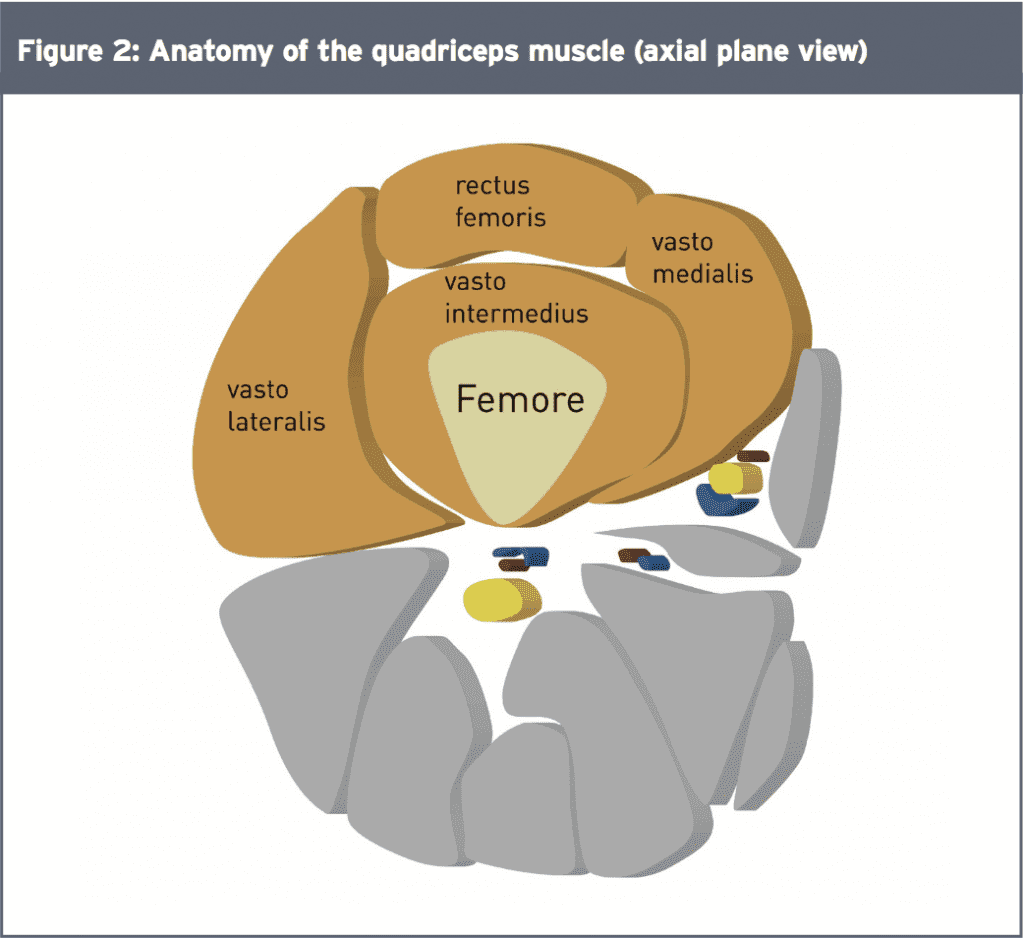

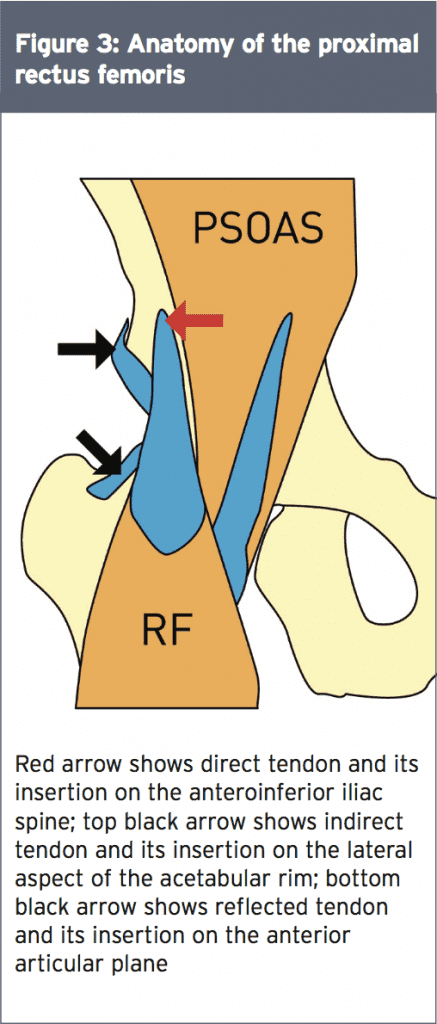

The quadriceps muscle is composed of four muscle bellies: rectus femoris (RF), which lies in the anterior portion of the thigh, vastus medialis (VM) and vastus lateralis (VL) on the inner and outer portions, respectively, and vastus intermedius (VI), which is located posteriorly (see Figures 1-3). The vastus muscles originate from the anterior, medial, and lateral aspects of the femur. The RF originates from the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS), and has three proximal tendons: the straight or direct tendon, which arises from the AIIS, the indirect tendon which inserts into the superolateral rim of the acetabulum, and a small reflected tendon, which inserts into the anterior capsule of the hip joint(2).

The four bellies converge distally to form the thick quadriceps tendon, which inserts into the superior pole of the patella. This tendon is composed of multiple laminae positioned one on top of the other. The superficial lamina is continuous with the muscle fibres of the RF. The intermediate lamina receives the fibres of the VM and VL, and the deepest lamina receives the fibres of the VI. A smaller percentage of fibres of the superficial lamina lie superficial to the patella and merge directly into the patellar tendon.

Aetiology Of Quadriceps Strains

There are a number of factors that increase the risk of a quadriceps strain. For example, high forces across the muscle-tendon units combined with eccentric contraction can lead to strain injury. Excessive passive stretching or activation of a maximally stretched muscle can also cause strains. Muscle fatigue has also been shown to play a role in acute muscle injury(3). This may account for the observation of increased injury risk during the pre-season (when fitness levels tend to be lower, leading to the earlier onset of fatigue). However, of the four bellies, the RF is most frequently strained(4-8). There are a number of factors behind the increased vulnerability of RF; as well as crossing two joints, it contains a high percentage of explosive ‘type-II fibres’ and also has a complex musculotendinous architecture, all of which are known to increase injury risk(9,10).

As noted in the NCAA study above, indirect trauma occurs for the most part as a result of eccentric contractions(4,11). This can occur, for example, when soccer or rugby players unexpectedly encounter irregular or slippery turf as they are about to kick a ball. As a result, they miscalculate the position or speed of the ball and try to compensate for their error by extending the hip. The muscle at risk in this situation is the RF, more specifically the proximal third of the RF.

This type of injury can also occur when athletes loses their footing during abrupt deceleration – something that is common in all sports that involve running. In some cases, the lesion involves the reflected tendon of the RF, which arises from the acetabular rim (Figure 3). These lesions may mimic hip pain or a lesion of the tensor fascia lata. The athlete frequently reports the sensation that ‘something in the hip has been displaced during the trauma and complains of pain in the region of the tensor fascia lata.

For contusions, diagnostic imaging is typically not necessary, but can be helpful in a few instances. Occasionally, a patient will present sub-acutely with anterior thigh pain without a known mechanism of injury. If this is the case, US and MRI can provide additional information regarding the nature of muscle injury. In particular, they can help differentiate between strain, contusion, or avulsion injuries(18). Where a localised haemotoma is present as a result of a contusion injury, US can provide a distinct advantage, providing real-time imaging for needle aspiration.

References

1. J Athl Train. 2017 Apr 6. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.2.17. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Clin Anat 2009;22:436e50

3. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:137–4

4. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:500–6

5. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:493–9

6. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:S2–8

7. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:1099–106

8. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:710–9

9. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:745–64

10. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14:669–86

11. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:818e24

12. Clin Sports Med. 1988;7:611–24

13. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;403S:S110–9

14. J Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55A:95–105

15. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:299–304

16. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:1323–9

17. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14:899–905

18. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:S103–20

19. DeLee JC, Drez D, Miller MD. Orthopaedic sports medicine: principles and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003

20. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25:138–45

This type of injury can also occur when athletes loses their footing during abrupt deceleration – something that is common in all sports that involve running. In some cases, the lesion involves the reflected tendon of the RF, which arises from the acetabular rim (Figure 3). These lesions may mimic hip pain or a lesion of the tensor fascia lata. The athlete frequently reports the sensation that ‘something in the hip has been displaced during the trauma and complains of pain in the region of the tensor fascia lata.

Diagnosis (Quadriceps Strain)

The diagnosis of a quadriceps strain and/or contusion requires knowledge of the patient’s history together with a physical examination. Imaging may also be a useful adjunct in those cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or further detail is needed regarding the type and location of the muscle strain.- Patient history – Athletes that suffer an acute quadriceps strain will usually know right away. Typically, a sharp pain is felt associated with a loss in function of the quadriceps. However, in some instances, the pain may come on gradually, only to be felt fully at the end of a game or practice session. As well as the pain, there may be swelling and loss of motion. Although pain can be experienced anywhere along the quadriceps, it is classically reported along the distal portion of the rectus femoris at the musculotendinous junction. That said, the literature shows that quadriceps strains at the mid to proximal portion of the rectus femoris are quite common too(4,5).

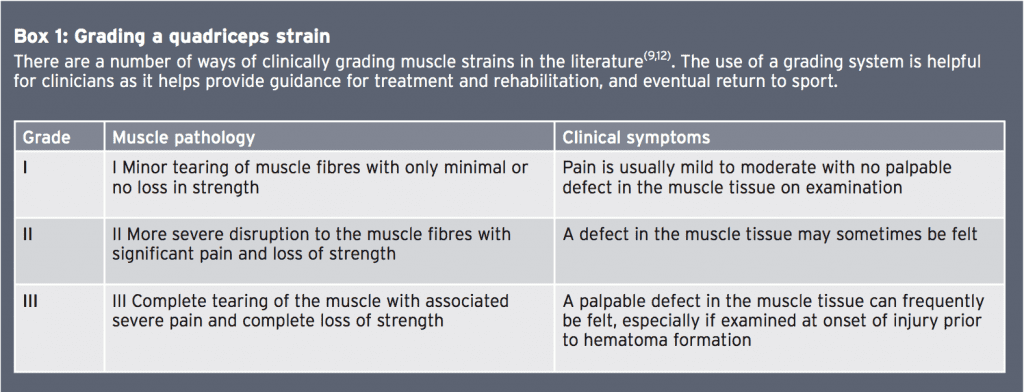

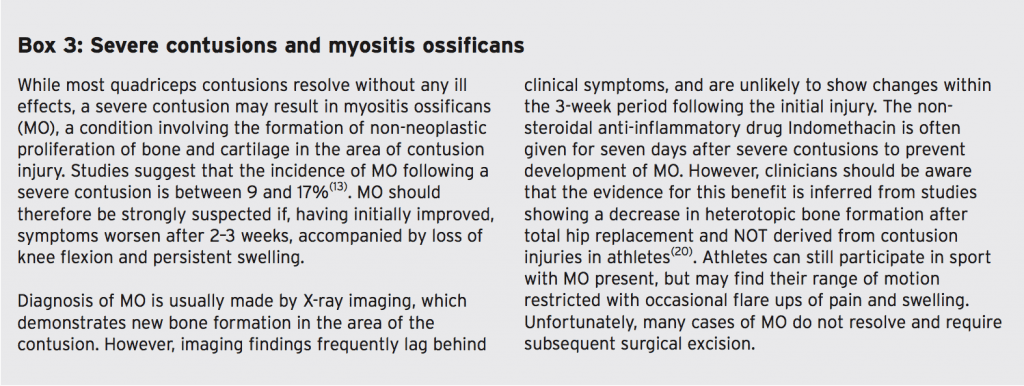

- Physical examination – a thorough examination will require observation, palpation, strength testing, and evaluation of motion. Strain injuries of the quadriceps may present with an obvious deformity such as a bulge or defect in the muscle belly – however, ecchymosis (bleeding under the skin) may not develop until 24 hours after the actual injury. Clinicians will need to palpate the entire length of the injured muscle, locating the area of maximal tenderness and feeling for any defects in the muscle. Following on, strength testing should include resistance of knee extension and hip flexion. To test RF, knee extension testing should be carried out with the hip both flexed and extended. Practically, this is best accomplished by evaluating the patient in both a sitting and prone-lying position (which also allows for optimum assessment of quadriceps motion and flexibility more generally). Assessing the degree of tenderness, palpable defects, and strength/ functionality will determine the grading of the injury, which helps provide direction for further diagnostic testing and treatment (see Box 1).

Diagnosis Of Quadriceps (Contusion)

The usual mechanism of this injury is a direct blow to the quadriceps causing significant muscle damage. Typically, a contusion involves rupture to the muscle fibres at, or directly adjacent to, the area of impact. This usually leads to hematoma formation within the muscle causing pain and loss of motion. A contracted muscle will absorb force better and result in a less severe injury than a relaxed muscle(13) – something that can provide useful context for clinicians taking a history.- Patient history – Athletes will usually report a definite impact mechanism associated with a contusion injury such as a direct blow from an opponent’s knee or other piece of equipment. This information is important for differentiating strain and contusion injuries. Athletes also typically report localised pain at the site of injury, swelling, decreased range of motion, and tenderness. Depending on the severity of injury, some athletes may be able to continue their activity, only seeking treatment after competition or training.

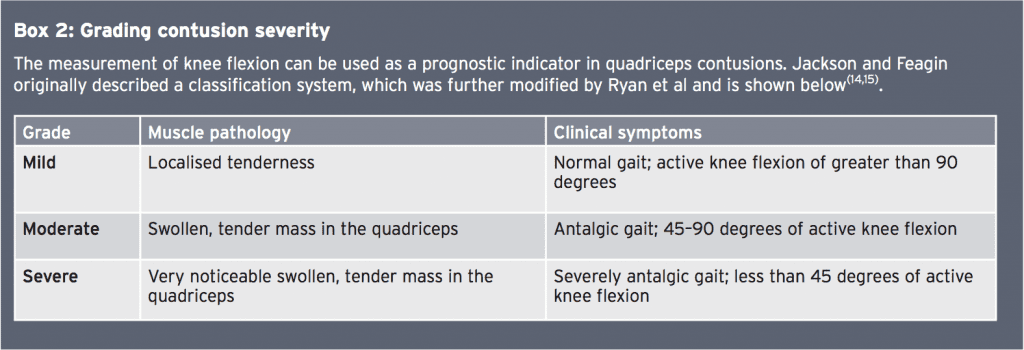

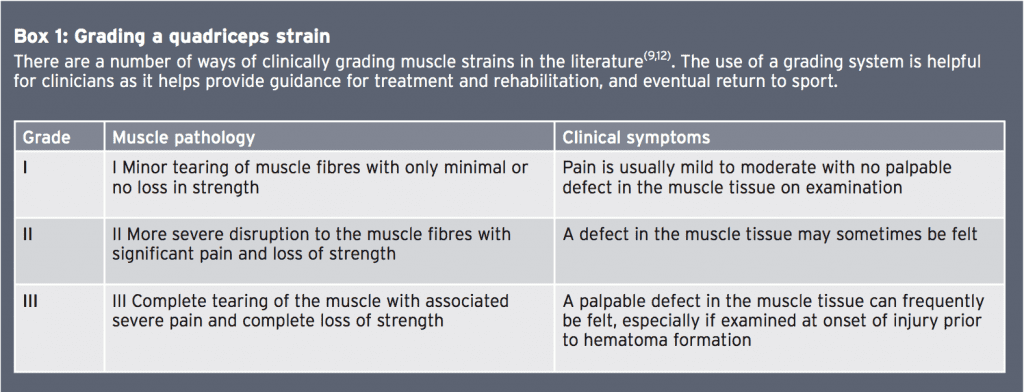

- Physical examination – Upon examination, clinicians should inspect the area of injury for obvious signs of deformity, swelling, or ecchymosis. Palpation along the injured muscle will help localise the exact site of muscle damage and determine if there is any associated injury. Strength testing of the quadriceps should assess resisted knee extension and hip flexion; by comparing the findings to those of the uninjured side, the severity of injury can be determined (see Box 2).

Imaging Of Strains & Contusions

Most acute injuries to the quadriceps can be diagnosed with an adequate history from the patient and a thorough examination. However, imaging can be a useful adjunct in cases of quadriceps strain where the diagnosis is uncertain or further detail is needed regarding the type and location of the muscle strain – for example small, partial tears or for estimating the size of a tear.- Ultrasonography (US) – is widely used and has a number of advantages, including widespread availability and low cost. It can also be used for dynamic studies of the muscle during contraction and relaxation, and if doubts arise, scans can easily be obtained of the contralateral muscle for comparison purposes. These qualities make it an excellent tool for follow-up of patients with quadriceps muscle lesions, when follow-up is necessary. The caveat is that US is highly operator dependent, and requires a skilled and experienced clinician to obtain the best results(16,17).

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – is also an excellent imaging technique – thanks to its superior tissue contrast, it allows simultaneous assessment of muscle, joint, and bone planes. However, US generally remains a second-choice technique due to its high cost and relatively low availability. Also, It can sometimes be difficult to distinguish between muscular contusion and strain on MRI, which simply re-enforces the importance of a thorough initial clinical history and examination by the sports clinician(18,19).

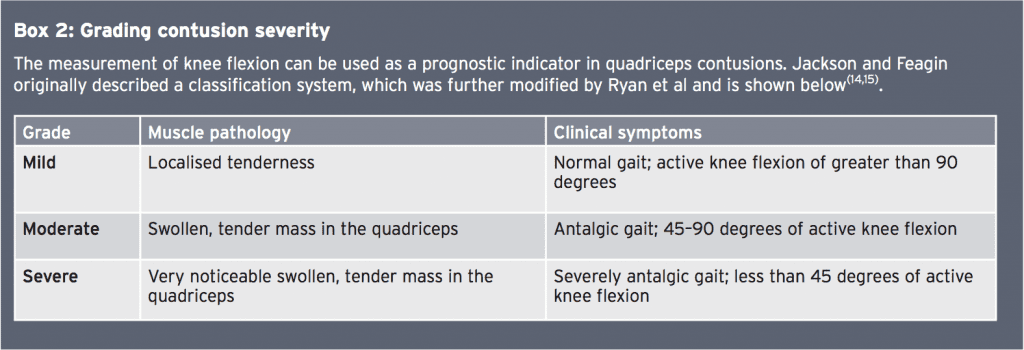

- Conventional radiography – although muscles cannot be visualised with conventional radiography, it is often recommended in pre-pubertal patients because it can detect apophyseal detachments, which are the most frequent muscle lesion in this age group. Radiography is also useful when myositis ossificans is suspected (see Box 3).

For contusions, diagnostic imaging is typically not necessary, but can be helpful in a few instances. Occasionally, a patient will present sub-acutely with anterior thigh pain without a known mechanism of injury. If this is the case, US and MRI can provide additional information regarding the nature of muscle injury. In particular, they can help differentiate between strain, contusion, or avulsion injuries(18). Where a localised haemotoma is present as a result of a contusion injury, US can provide a distinct advantage, providing real-time imaging for needle aspiration.

References

1. J Athl Train. 2017 Apr 6. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-52.2.17. [Epub ahead of print]

2. Clin Anat 2009;22:436e50

3. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:137–4

4. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:500–6

5. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:493–9

6. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:S2–8

7. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:1099–106

8. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:710–9

9. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:745–64

10. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14:669–86

11. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:818e24

12. Clin Sports Med. 1988;7:611–24

13. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;403S:S110–9

14. J Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55A:95–105

15. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:299–304

16. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:1323–9

17. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14:899–905

18. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:S103–20

19. DeLee JC, Drez D, Miller MD. Orthopaedic sports medicine: principles and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003

20. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25:138–45