Chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez looks at the diagnosis of and treatment options for popliteal artery entrapment, a poorly understood condition that can affect otherwise healthy athletes…

Popliteal artery entrapment syndrome (PAES) occurs when muscles that surround the popliteal artery in the area of the popliteal fossa, occlude the artery (and sometimes the vein as well), and decrease blood flow to the lower leg. Two forms of PAES exist: anatomical and functional.

The symptoms remain the same, no matter which type is the cause.

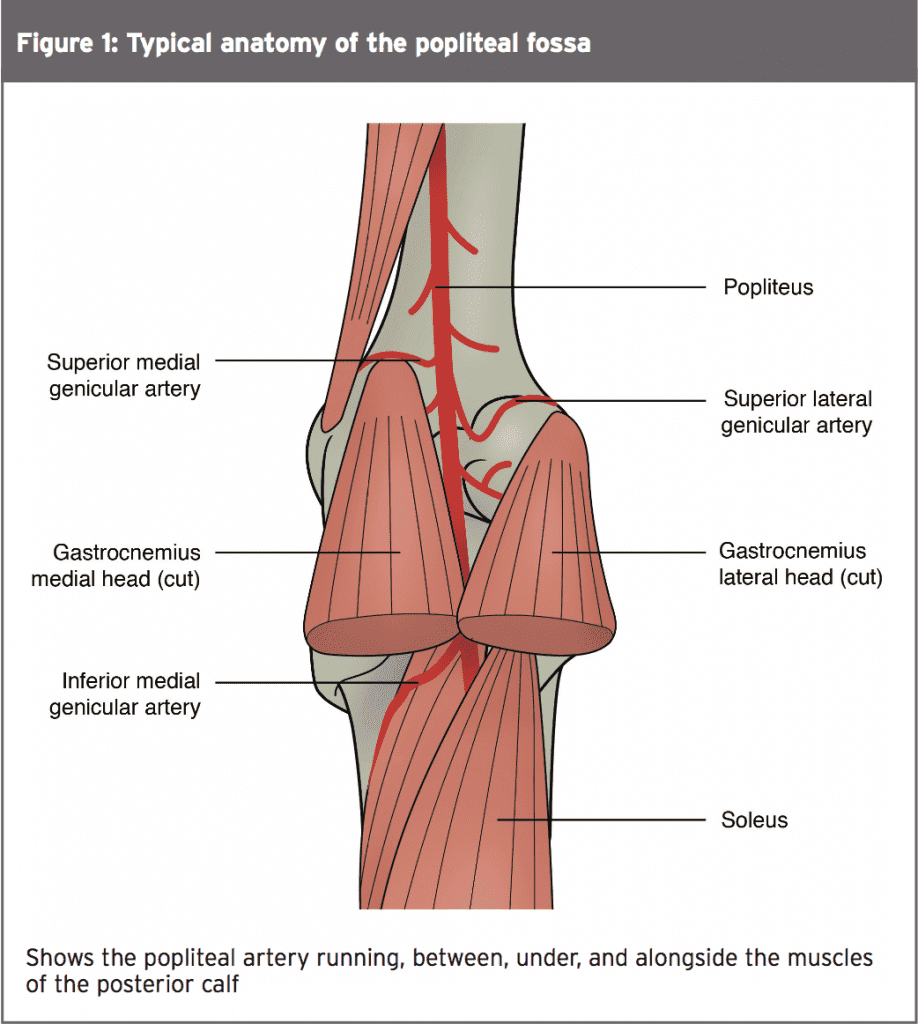

Typically, the popliteal artery tucks neatly between the heads of the gastrocnemius; alongside the plantaris; over the popliteus; and under the soleus muscles (see Figure 1). In anatomical PAES, the abnormal positions of the artery, or the muscles that surround the artery, cause compression against the bone or another muscle.

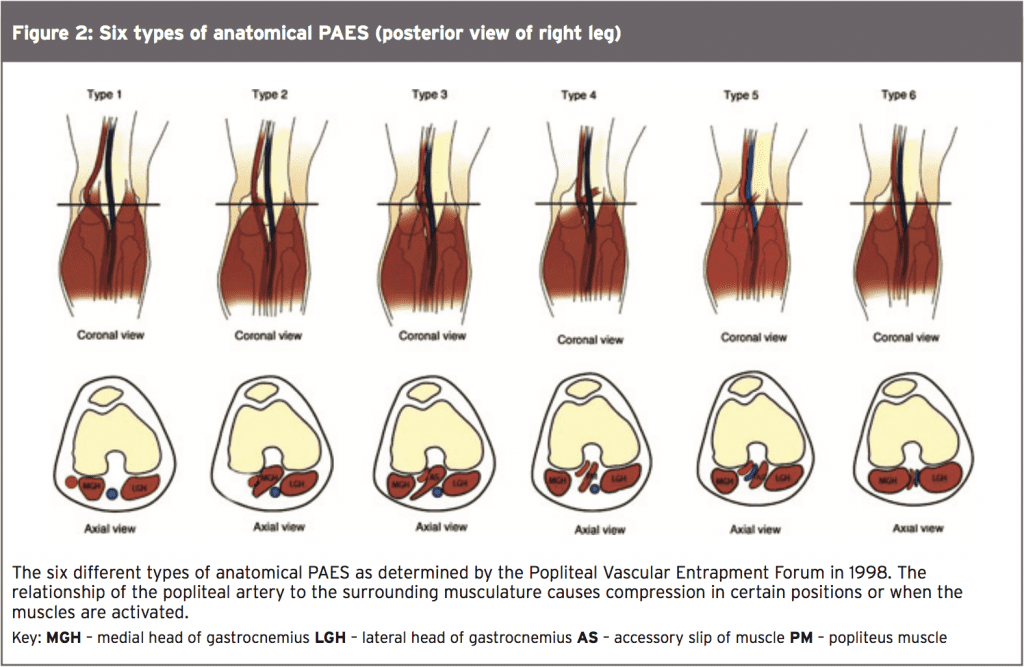

Despite the fact that it was first described in the literature in 1958, the formation of the popliteal vascular entrapment forum in 1998 marked the first consensus on the different anatomical types (see Figure 2 and Table 1)(1). Functional PAES occurs despite normal anatomy, and possibly due to compartment pressure or hypertrophy of the neighboring muscles.

Difficult Diagnosis

Considered rare, no one knows the actual incidence of PAES(2). Since the syndrome can occur alongside other pathologies in the leg, it is possibly underreported. Young athletes who present with symptoms of intermittent claudication most likely suffer from functional PAES. Anatomical PAES supposedly occurs in older, more sedentary persons.Athletes complain of a vague and generalised pain in the posterior calf, which can radiate anteriorly, depending on the involved anatomy. Sportsmen also report leg swelling, numbness, feelings of coldness in the leg or foot, and tingling. Pain begins after initiating activity, or with certain provocative manoeuvres. The pain usually resolves with rest, although an ache can persist.

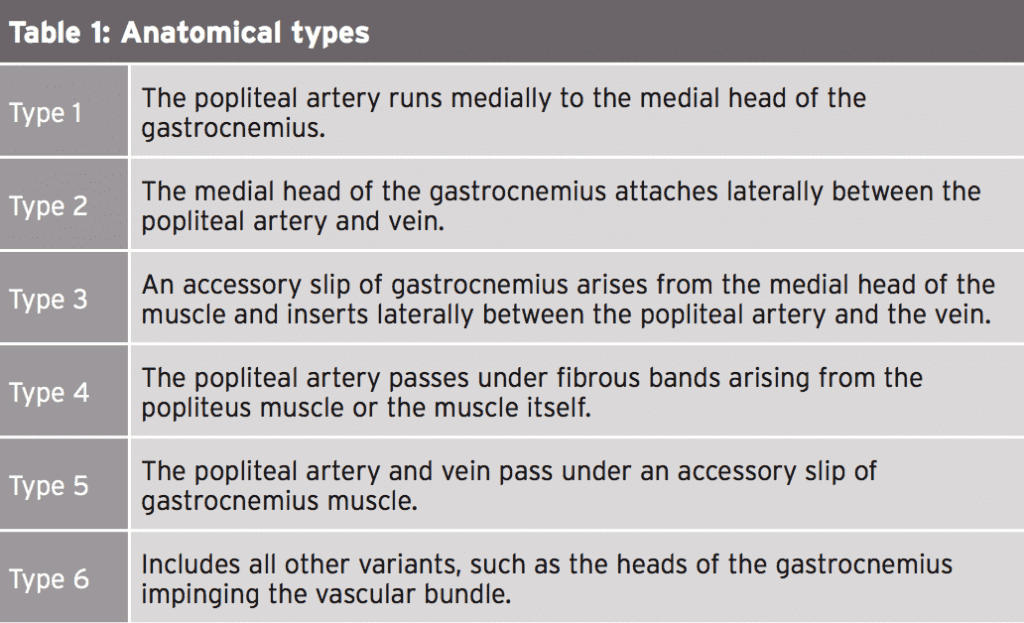

The difficulty in diagnosing PAES stems from the lack of consensus about diagnostic exams, symptoms that mimic or occur with other syndromes, and frequent findings of asymptomatic vascular occlusion (see Table 2).

Doppler ultrasound studies show that in subjects with popliteal artery compression, anywhere from 7% to 80% of this group are asymptomatic(2). Additionally, Doppler evaluations with provocation detect popliteal vein compression in up to 100% of this group(1)! Other causes of exertional leg pain include stress fracture, medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS), and chronic exertional compartment syndrome CECS.

Clinicians must first rule out bone stress or fracture when evaluating exertional leg pain. Many also perform clinical vascular provocation tests where they attempt to reproduce the pain in the clinic through exertion manoeuvres. They assess peripheral pulses, arterial bruits, or ankle brachial indices (comparing the difference in the blood pressure at the ankle versus the arm) before and after the provocation of symptoms.

At the Brisbane Sports and Exercise Medicine Specialists Clinic, doctors have developed a specific clinical exam for PAES(2). First, with the athlete at rest, they listen for a bruit or vascular murmur at the popliteal fossa (indicating a blockage of the artery) and examine the pulses in the lower leg. Then they ask the athlete to perform 15–20 heel drops off the edge of a step to try and reproduce the pain. Right after that test, they again listen to the artery at the popliteal fossa and evaluate peripheral pulses. They recommend listening for several minutes since complete occlusion will not make any sound until blood flow begins again.

These clinicians believe that a lack of pain on activity, an absence of bruits, or no change in pulses means the chance of the athlete suffering from PAES is small. However, if the test is positive for the above features, it does not necessarily mean that PAES causes the pain. There is the possibility that the athlete is an asymptomatic occluder, and a different pathology triggers the pain. Therefore, a clinical exam and leg pain are not sufficient to diagnose PAES; there must be evidence of actual vascular occlusion in conjunction with the pain.

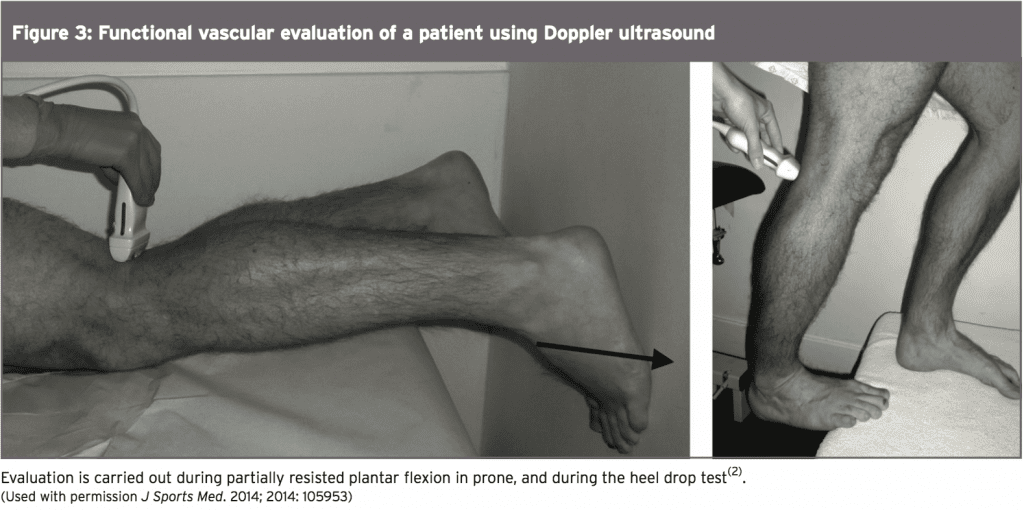

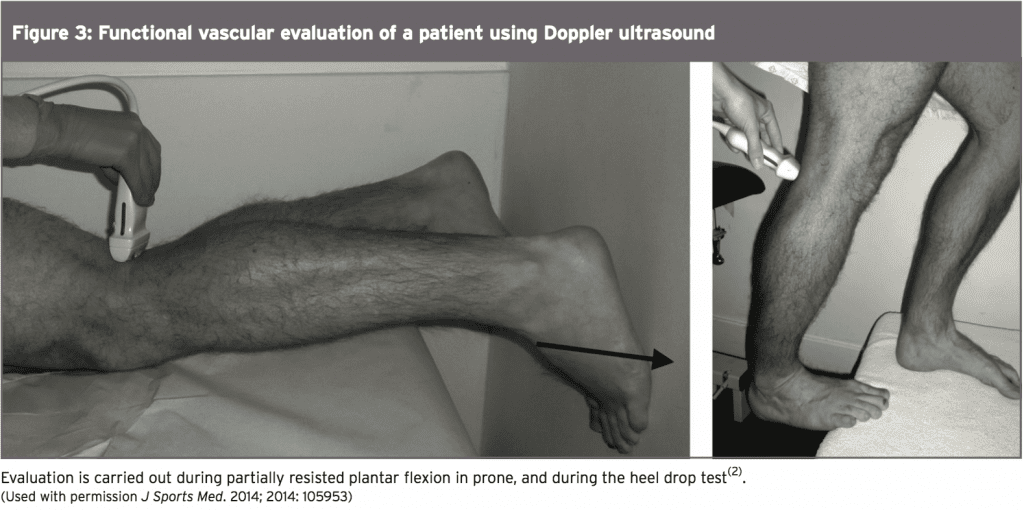

To document arterial occlusion, athletes undergo a Doppler ultrasound exam of the popliteal fossa. Examination of the artery takes place with the athlete lying in prone with the leg in the neutral position; while moving the ankle into plantar flexion against partial resistance, and with plantar flexion against full resistance while standing on toes or performing heel drops (see Figure 3). Occlusion found on ultrasound, combined with characteristic pain symptoms, is significant for both anatomical and functional PAES.

Even with a positive Doppler, many clinicians perform magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to fully visualize the anatomy, thereby recognizing any deviations that might result in anatomical PAES. MRI angiography (MRA) allows examiners to visualize the vasculature during movement, essential in functional PAES. Keep in mind that the results of the test can be skewed due to motion artifact on the images. Some clinicians conduct compartment pressure testing, primarily to rule out chronic compartment syndrome, as it doesn’t measure arterial occlusion. This can be a deception however because PAES can exist alongside compartment syndrome and be the primary cause of the pain.

Surgeons performed fasciectomy of the anterolateral and posterior compartments of both legs and the athlete experienced a typical recovery. However, the symptoms remained, especially with prolonged exertion. MRI evaluation appeared normal, but pressures measured in the deep posterior compartments of both legs proved abnormal at rest and after exercise. Therefore, the athlete again underwent fasciectomy of the deep posterior compartments.

The patient resumed full activity and progressed to win a national competition, however, after four months, the pain returned. All compartment pressures appeared normal. Evaluated now with a Doppler ultrasound, the athlete showed a decrease in arterial flow with resisted plantar flexion. Functional MRA revealed collapse of both arteries and veins bilaterally. Since the MRI showed normal anatomy the athlete was diagnosed with functional PAES.

Clinicians must first rule out bone stress or fracture when evaluating exertional leg pain. Many also perform clinical vascular provocation tests where they attempt to reproduce the pain in the clinic through exertion manoeuvres. They assess peripheral pulses, arterial bruits, or ankle brachial indices (comparing the difference in the blood pressure at the ankle versus the arm) before and after the provocation of symptoms.

At the Brisbane Sports and Exercise Medicine Specialists Clinic, doctors have developed a specific clinical exam for PAES(2). First, with the athlete at rest, they listen for a bruit or vascular murmur at the popliteal fossa (indicating a blockage of the artery) and examine the pulses in the lower leg. Then they ask the athlete to perform 15–20 heel drops off the edge of a step to try and reproduce the pain. Right after that test, they again listen to the artery at the popliteal fossa and evaluate peripheral pulses. They recommend listening for several minutes since complete occlusion will not make any sound until blood flow begins again.

These clinicians believe that a lack of pain on activity, an absence of bruits, or no change in pulses means the chance of the athlete suffering from PAES is small. However, if the test is positive for the above features, it does not necessarily mean that PAES causes the pain. There is the possibility that the athlete is an asymptomatic occluder, and a different pathology triggers the pain. Therefore, a clinical exam and leg pain are not sufficient to diagnose PAES; there must be evidence of actual vascular occlusion in conjunction with the pain.

To document arterial occlusion, athletes undergo a Doppler ultrasound exam of the popliteal fossa. Examination of the artery takes place with the athlete lying in prone with the leg in the neutral position; while moving the ankle into plantar flexion against partial resistance, and with plantar flexion against full resistance while standing on toes or performing heel drops (see Figure 3). Occlusion found on ultrasound, combined with characteristic pain symptoms, is significant for both anatomical and functional PAES.

Even with a positive Doppler, many clinicians perform magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to fully visualize the anatomy, thereby recognizing any deviations that might result in anatomical PAES. MRI angiography (MRA) allows examiners to visualize the vasculature during movement, essential in functional PAES. Keep in mind that the results of the test can be skewed due to motion artifact on the images. Some clinicians conduct compartment pressure testing, primarily to rule out chronic compartment syndrome, as it doesn’t measure arterial occlusion. This can be a deception however because PAES can exist alongside compartment syndrome and be the primary cause of the pain.

A Red Herring?

Doctors in Barcelona have reported the case of a 16-year-old female Olympic tae-kwon-do fighter who developed persistent and progressive pain in her calf(3). Pulses remained normal after clinical provocation of symptoms. Musculature anatomy was normal on ultrasound. Because the pain improved with rest, doctors suspected chronic compartment syndrome. Testing measured abnormal compartment pressure at rest, which remained unchanged with exercise.Surgeons performed fasciectomy of the anterolateral and posterior compartments of both legs and the athlete experienced a typical recovery. However, the symptoms remained, especially with prolonged exertion. MRI evaluation appeared normal, but pressures measured in the deep posterior compartments of both legs proved abnormal at rest and after exercise. Therefore, the athlete again underwent fasciectomy of the deep posterior compartments.

The patient resumed full activity and progressed to win a national competition, however, after four months, the pain returned. All compartment pressures appeared normal. Evaluated now with a Doppler ultrasound, the athlete showed a decrease in arterial flow with resisted plantar flexion. Functional MRA revealed collapse of both arteries and veins bilaterally. Since the MRI showed normal anatomy the athlete was diagnosed with functional PAES.

Surgical exploration revealed a hypertrophied plantaris muscle tendon compressing the popliteal vascular bundle. Surgeons removed a portion of the offending tendon, leaving the muscle belly intact. The athlete experienced a full recovery and a complete return to competition, without further incident of calf pain. This case demonstrates that symptoms of intermittent claudication, even in a young athlete, should always warrant a full exploration of vascular integrity, regardless of compartment pressures.

Functional PAES may be more difficult to treat effectively. Surgery in these situation appears somewhat less effective, with an average success rate around 80%(2). With the presence of normal anatomy, surgeons can only guess where the occlusion takes place and where to target intervention.

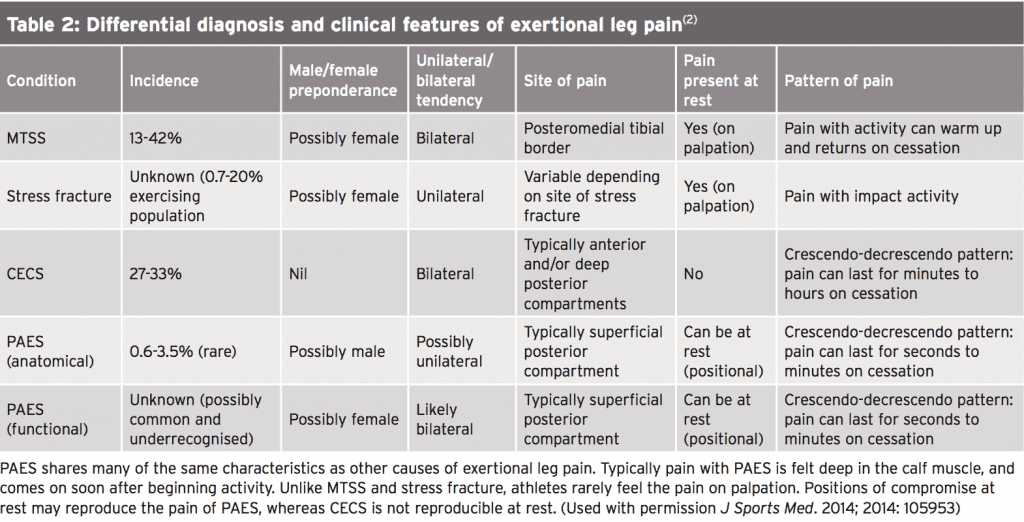

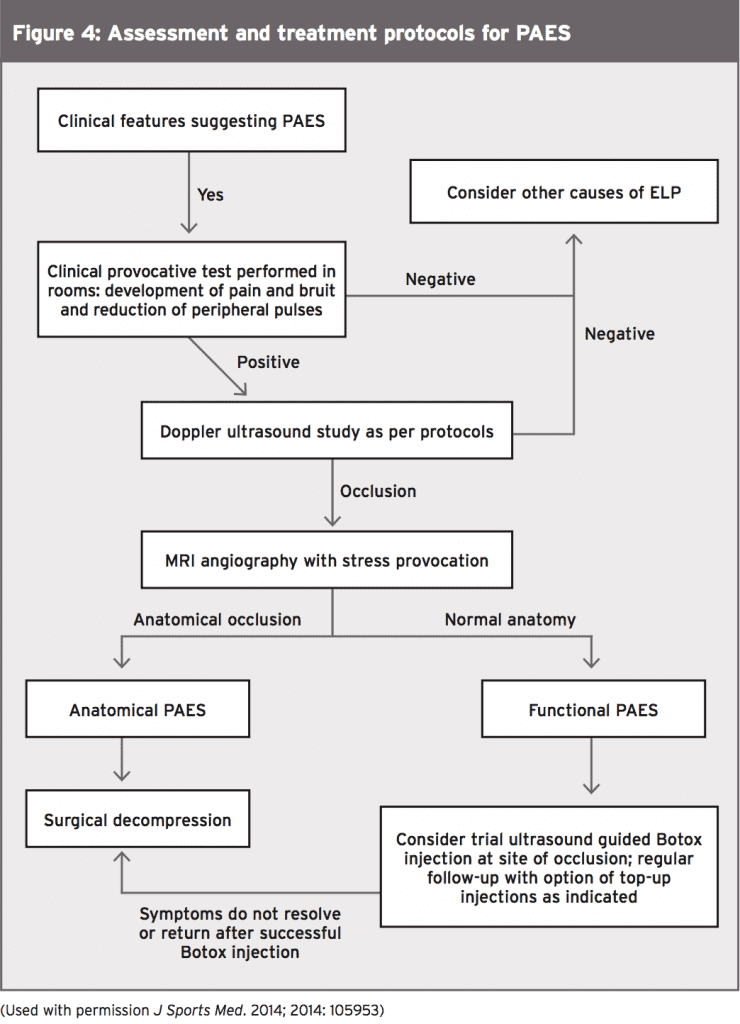

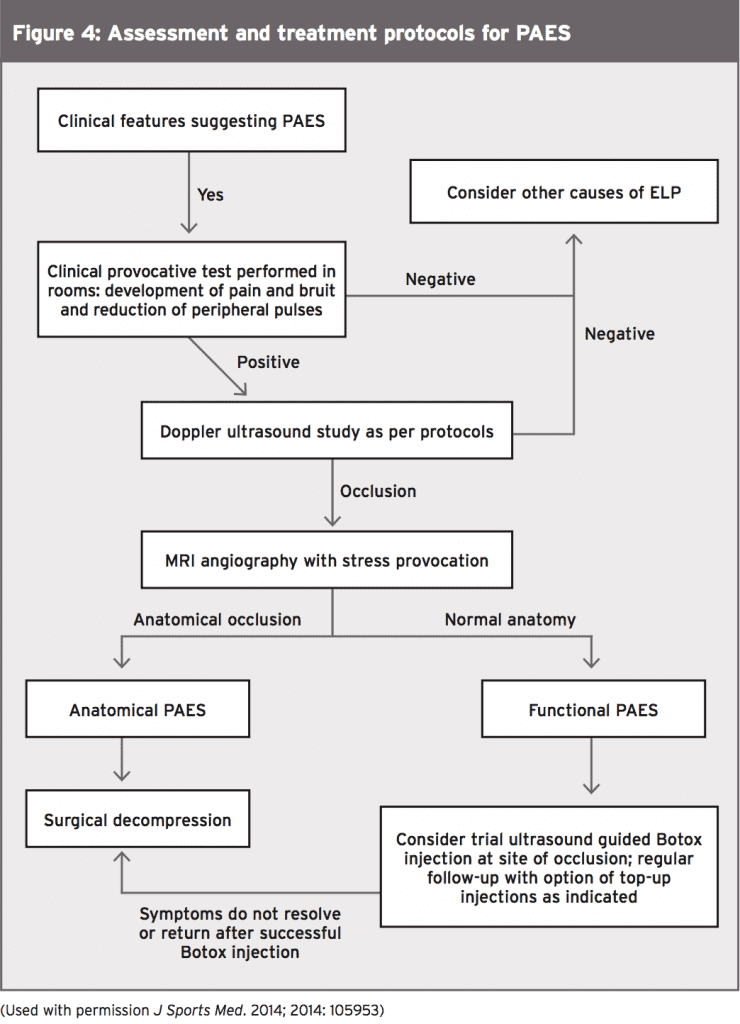

Doctors at the Brisbane Sports and Exercise Medicine Specialists Clinic are pioneering a new treatment for functional PAES. They have obtained promising results by treating athletes with guided botulinum injections(2). They hypothesise that by paralysing the offending muscle surrounding the vessel, they remove the constriction on the artery. They further surmise that the localised muscle atrophy caused by the botulinum accounts for the prolonged effect of the medication beyond its expected therapeutic life. Further, they propose that the botulinum causes smooth muscle relaxation and therefore popliteal artery vasodilation. This new treatment gives athletes another option for treatment with fewer risks (see Figure 4).

Being aware of the different causes of exertional leg pain allows the clinician to explore all possibilities and make a sound diagnosis. Doppler ultrasound, MRI and MRA, as well as a thorough clinical exam help guide decision-making. Characteristic pain on exertion or provocation, and evidence of vascular occlusion are indicators of PAES. Surgery is the most likely treatment for PAES and return to sport statistics are high. Promising new treatments like guided botulinum injections give hope for both a low risk treatment and also a more accurate diagnostic tool.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:252-62

2. J Sports Med. 2014; 2014: 105953

3. J Sports Sci Med. 2011 Dec; 10(4): 768–770

Treatment

In cases of anatomical PAES, surgery is almost always the most effective treatment. Because the types of entrapment vary, surgery can include fasciotomy, removal of the offending bands of muscle, muscle transfer, fossa decompression, or any combination of the above. Results are nearly always positive, with more than 90% of athletes who undergo this type of surgery fully returning to sport within three months(2).Functional PAES may be more difficult to treat effectively. Surgery in these situation appears somewhat less effective, with an average success rate around 80%(2). With the presence of normal anatomy, surgeons can only guess where the occlusion takes place and where to target intervention.

Doctors at the Brisbane Sports and Exercise Medicine Specialists Clinic are pioneering a new treatment for functional PAES. They have obtained promising results by treating athletes with guided botulinum injections(2). They hypothesise that by paralysing the offending muscle surrounding the vessel, they remove the constriction on the artery. They further surmise that the localised muscle atrophy caused by the botulinum accounts for the prolonged effect of the medication beyond its expected therapeutic life. Further, they propose that the botulinum causes smooth muscle relaxation and therefore popliteal artery vasodilation. This new treatment gives athletes another option for treatment with fewer risks (see Figure 4).

Conclusion & Summary

Exertional leg pain is a clinical enigma. When pain only occurs during exercise and without palpable or visible evidence, a trainer often takes a ‘wait and see’ attitude. However, intermittent claudication from PAES, can cause arterial and tissue damage if left untreated.Being aware of the different causes of exertional leg pain allows the clinician to explore all possibilities and make a sound diagnosis. Doppler ultrasound, MRI and MRA, as well as a thorough clinical exam help guide decision-making. Characteristic pain on exertion or provocation, and evidence of vascular occlusion are indicators of PAES. Surgery is the most likely treatment for PAES and return to sport statistics are high. Promising new treatments like guided botulinum injections give hope for both a low risk treatment and also a more accurate diagnostic tool.

References

1. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:252-62

2. J Sports Med. 2014; 2014: 105953

3. J Sports Sci Med. 2011 Dec; 10(4): 768–770