In the first part of his two-piece review on psoas major (PM), Dr. Alexander Jimenez discussed the relevant and complex anatomy and biomechanics of this unique and misunderstood muscle. In part two, Dr. Jimenez looks at how PM dysfunction may manifest as a musculoskeletal problem, and the corrective interventions a therapist can use to manage PM dysfunction.

PM & Lumbar Back Pain

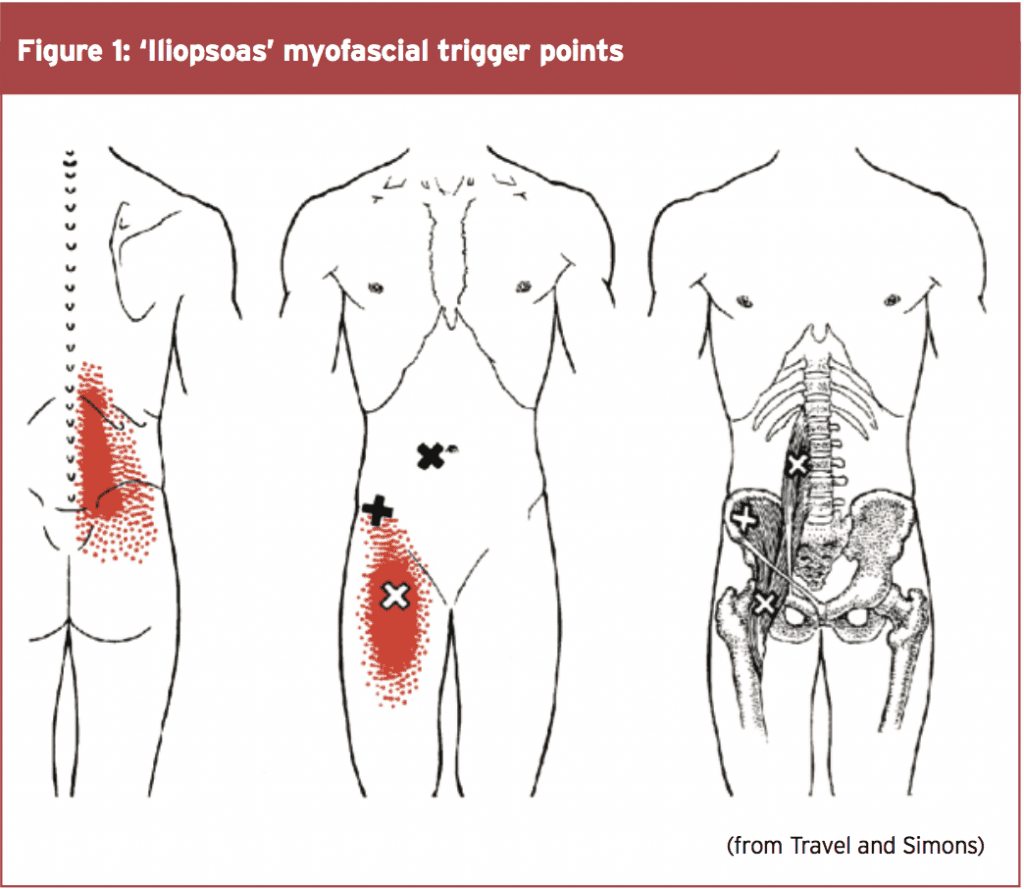

Anecdotally, many therapists clinically find that patients with acute low back pain have myofascial trigger points in the PM when the muscle is palpated. Often deep trigger point releases into the PM can help alleviate and reduce the symptoms of low back pain. However, it is unclear whether the clinical correlation between low back pain and PM hypertonicity is causative. Is the hypertonic PM the cause of the back pain, or does it reflexively tighten up in the presence of back pain as a protective mechanism?In the ageless text ‘Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction’ by Janet Travel and David Simons, the iliopsoas is referred to as the ‘hidden prankster’(1). They argue that the muscle is deep, hard to locate and can often hide trigger points that can masquerade as low back pain, which extends up and down the spine on the same side as the PM dysfunction (see Figure 1 below).

Often patients who complain of PM trigger points will complain of a deep unilateral low back pain that radiates up and down the spine, with possible referral into the anterior thigh and groin area. Often the pain is felt to be worse when standing upright, lying flat on the back and relieved by sitting down.

The primary weakness in this clinical view is that the differentiation between PM and iliacus is not made. It is possible that if the PM and iliacus are indeed separate functional muscles then these myofascial trigger points may exist in the iliacus and not necessarily the PM. What is also interesting is that Travel and Simons do note the close association between the PM and nerves such as the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and obturator. Due to the close proximity of the PM to these nerves, it may be also clinically argued that hypertonicity in the PM may compress and/or irritate these nerves, and this may manifest with the client complaining of groin pain or pain into the perineum area.

These ideas are further supported by Johnson et al (1998), who stated that myofascial pain from the PM muscle will often present as anterior hip and/or lower back pain(2). Referral areas include the anterior thigh. The PM muscle can be considered as a pain source in athletes, office workers or anyone who spends much of their day sitting. PM myofascial pain is thought to be prevalent in certain sports including soccer, dance, and hockey.

More recently there has been some research that highlights the association between low back pain and PM dysfunction. Some of the findings of these studies are as follows:

1. In a cohort study examining the cross- sectional area of the PM in healthy volunteers and subjects with unilateral sciatica caused by a disc herniation, most patients with a lumbar disc herniation showed a significant reduction in the cross-sectional area of the PM on the affected side only and most prominently at the level of the disc herniation(3).

2. This was further supported in a study that investigated the cross-sectional area of the PM in the presence of unilateral low-back pain through the utilisation of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It was found that the cross-sectional area of the bilateral PM was on average 12% smaller on the side of the low-back pain. Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between a decreased cross-sectional area of the PM and the duration of symptoms(4).

3. These studies correlate well with other studies that have found specific atrophy in multifidus in patients with low-back pain. The same mechanism of inhibition due to perceived pain may be responsible for the PM atrophy(5).

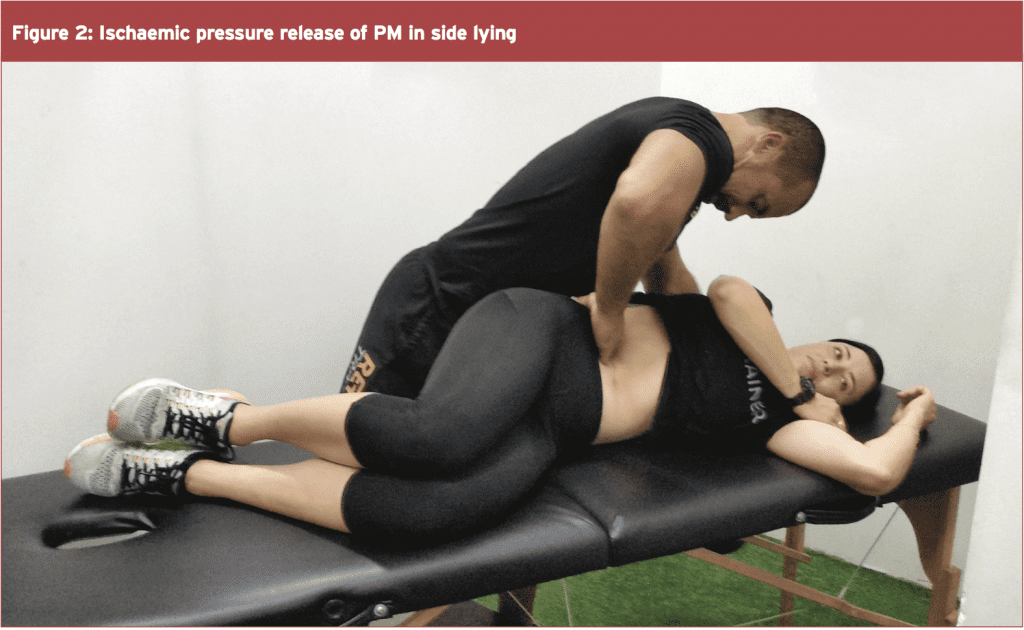

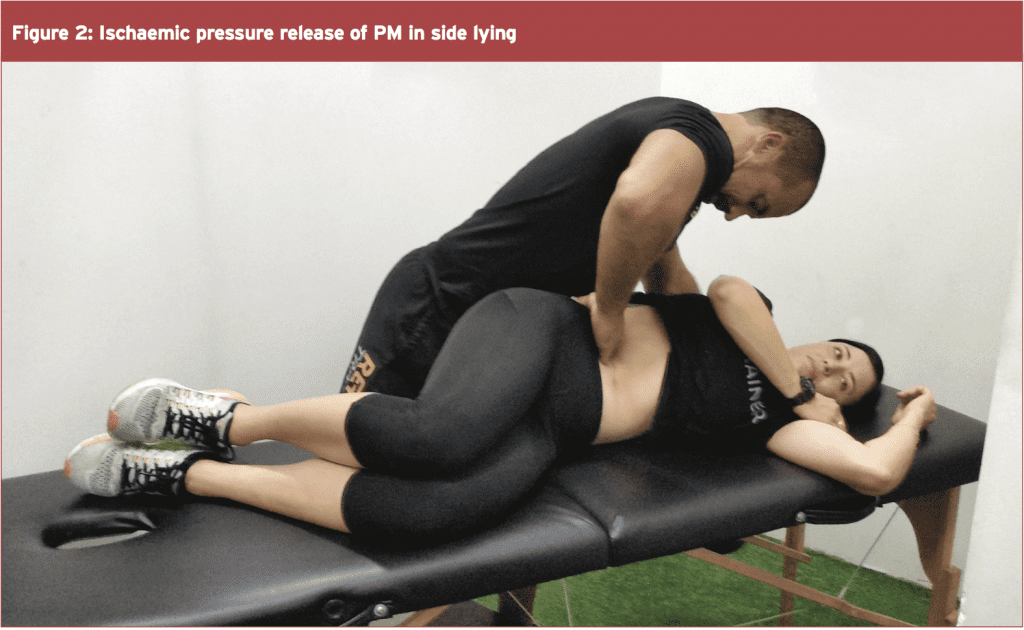

These approaches can be performed in many ways. However one of the preferred ways is to have the client lie on their side. This is a comfortable position for the client to lie in as the abdominals relax and it is easier for the therapist to palpate the PM. Furthermore, the abdominal organs will displace medially in this posture, which means the therapist is unlikely to be creating discomfort to the intra- abdominal organs. This technique is shown in Figure 2.

This action creates axial compression along the lumbar vertebral segments, thus increasing lumbar spine rigidity, which in turn increases stability. Furthermore, the femoral insertion of the PM will displace the head of the femur up in the acetabulum and create hip joint stability, and prevent excessive anterior shear forces acting on the hip joint. Therefore, an effective PM contraction will stabilise and resist translational movements in the hip joint, sacroiliac joint and lumbar spine joints.

The essential cue for the therapist to teach the client is an action of ‘pulling in the hip’ or ‘shortening the leg’. This movement needs to be very specific to the hip joint and not created by lateral tilt or ‘hitching’ of the pelvis, anterior or posterior tilt of the pelvis or rotation of the pelvis. Moreover, this needs to be performed against a background of sound diaphragmatic breathing control.

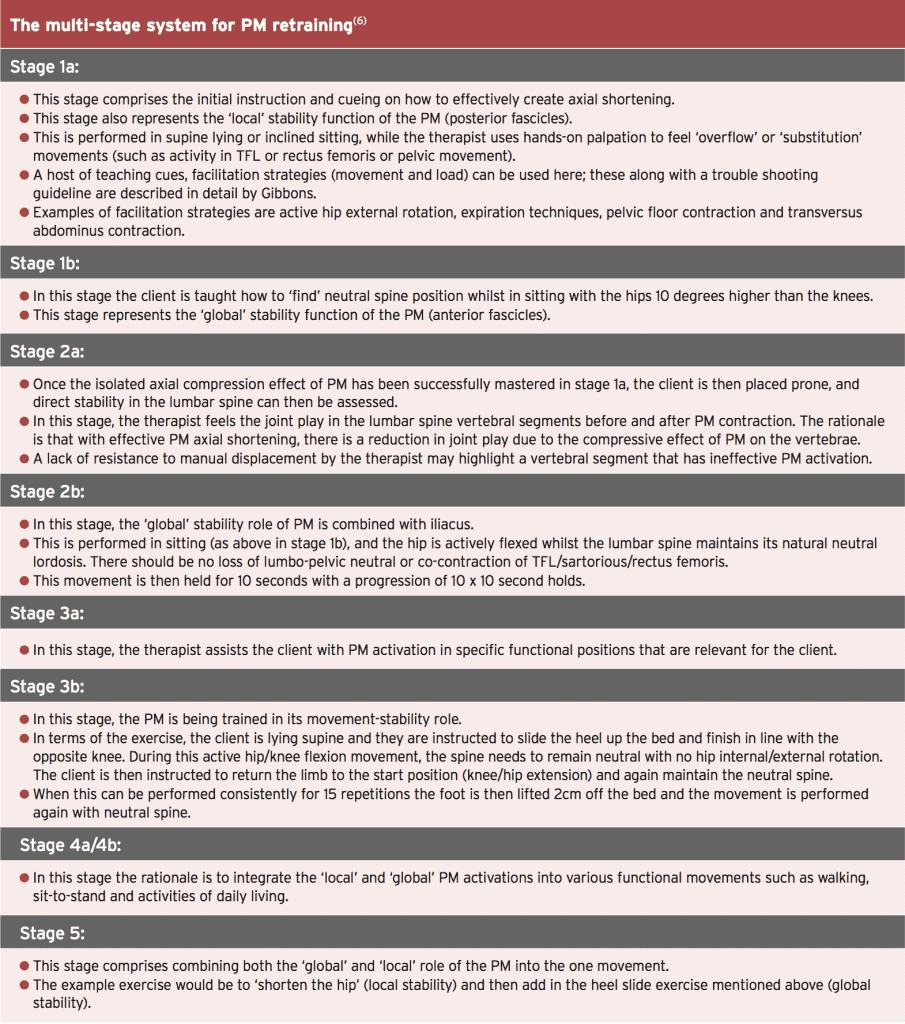

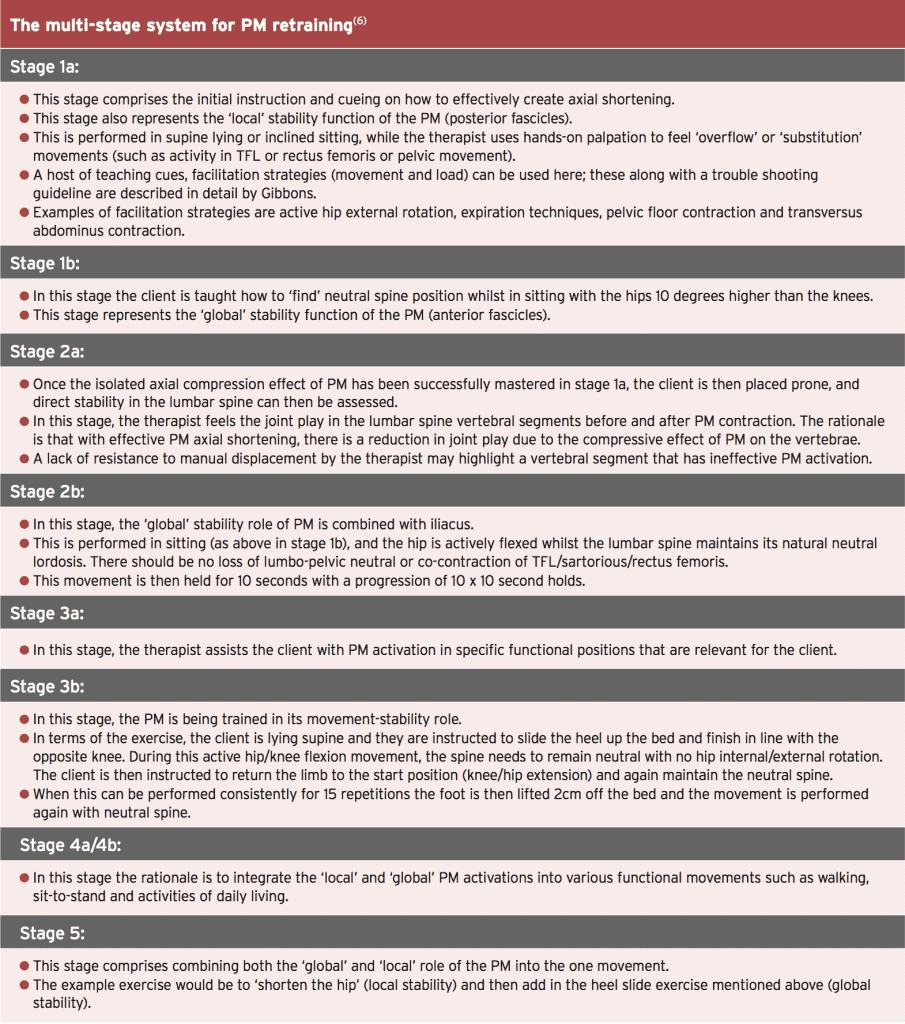

It is beyond the scope of this paper to describe in detail the multi-stage system of retraining PM function. The reader is therefore directed to the reference given for more precise details on how this system is utilised in retraining PM function. However, in summary, the primary points to note in each stage opposite.

It is now thought that the PM has many functional roles and these are primarily due to the unique anterior and posterior fascicle arrangement. This suggests that the posterior fascicles are important lumbar spine stabilisers, and work in connection with other spine stabilisers as an integrated complex of myofascial tissue.

3. These studies correlate well with other studies that have found specific atrophy in multifidus in patients with low-back pain. The same mechanism of inhibition due to perceived pain may be responsible for the PM atrophy(5).

Assessment Of PM Dysfunction

Due to the deep position of the PM and the difficulty in accessing the muscle directly, PM dysfunction is often inferred based on clinical signs and symptoms. These include the location of low-back pain (usually believed to be alongside the spine in a vertical direction), the primary positions of discomfort such as lying flat on the back or standing up straight, and perhaps also in the presence of poorly functioning transversus abdominus that may lead the PM to ‘overcompensate’ in its role as a lumbo-pelvic stabiliser.

A simple clinical assessment would be to palpate the PM, and apply gentle ischaemic pressure to the muscle to relieve some active myofascial trigger points. Painful movements can then be reassessed to determine the role that PM trigger points may have in the presentation of the patient’s low-back pain.

PM also has a role to play in creating lumbar spine stiffness due to its action as an axial compressor of the spine. This function can directly be assessed in terms of the ability of the client to activate the PM, with the therapist then assessesing joint play of the vertebrae before and after activation (Gibbons 2007)(6). This process is described below under retraining of the PM.

PM also has a role to play in creating lumbar spine stiffness due to its action as an axial compressor of the spine. This function can directly be assessed in terms of the ability of the client to activate the PM, with the therapist then assessesing joint play of the vertebrae before and after activation (Gibbons 2007)(6). This process is described below under retraining of the PM.

Managing Myofascial ‘Tightness’ In The PM

As mentioned above, it is a long-held historical clinical belief that PM may become tight and develop myofascial trigger points, and be the source of, or consequence of low-back pain. With this in mind, many clinicians and therapists apply direct massage techniques, digital pressure ischaemic techniques and stretching exercises to directly manage the myofascial trigger points and tightness.These approaches can be performed in many ways. However one of the preferred ways is to have the client lie on their side. This is a comfortable position for the client to lie in as the abdominals relax and it is easier for the therapist to palpate the PM. Furthermore, the abdominal organs will displace medially in this posture, which means the therapist is unlikely to be creating discomfort to the intra- abdominal organs. This technique is shown in Figure 2.

Retraining PM Function

The credit for the following content on retraining PM weakness and dysfunction is given to Gibbons, who has collated a comprehensive exercise battery on retraining PM dysfunction(6). In this extensive review on PM retraining, Gibbons explains how the specific motor control and stability exercises for the PM involve axial shortening, or attempting to bring the insertion closer to the origin along its vertical axis.This action creates axial compression along the lumbar vertebral segments, thus increasing lumbar spine rigidity, which in turn increases stability. Furthermore, the femoral insertion of the PM will displace the head of the femur up in the acetabulum and create hip joint stability, and prevent excessive anterior shear forces acting on the hip joint. Therefore, an effective PM contraction will stabilise and resist translational movements in the hip joint, sacroiliac joint and lumbar spine joints.

The essential cue for the therapist to teach the client is an action of ‘pulling in the hip’ or ‘shortening the leg’. This movement needs to be very specific to the hip joint and not created by lateral tilt or ‘hitching’ of the pelvis, anterior or posterior tilt of the pelvis or rotation of the pelvis. Moreover, this needs to be performed against a background of sound diaphragmatic breathing control.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to describe in detail the multi-stage system of retraining PM function. The reader is therefore directed to the reference given for more precise details on how this system is utilised in retraining PM function. However, in summary, the primary points to note in each stage opposite.

Conclusion

The PM is a unique, complex and misunderstood muscle that has for many years been described as primarily a hip flexor along with iliacus. However, new research suggests that the PM is quite complex in its anatomical arrangement with the lumbar spine, pelvic rim/brim and femur, and also its attachments to the diaphragm, pelvic floor and iliacus.It is now thought that the PM has many functional roles and these are primarily due to the unique anterior and posterior fascicle arrangement. This suggests that the posterior fascicles are important lumbar spine stabilisers, and work in connection with other spine stabilisers as an integrated complex of myofascial tissue.

Dysfunction of the PM may manifest as hypertonicity in the muscle, which may suggest to a clinician that the muscle is compensating for dysfunction in other lumbar stabiliser muscles. It may also become dysfunctional in motor control and not provide sufficient axial compression of the lumbo-pelvic girdle. A series of motor retraining exercises can be used to regain this function.

References

1. Travel and Simons. Myofascial Pain and

Dysfunction. The Lower Extremities (Volume 2).

Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Philadelphia.

2. Sports Med. 1998; 25(4):271–283

3. Spine. 1998; 23(8):928-931

4. Spine. 2008; 33(26): E983–E989.

5. Spine. 1994; 19(2):165-172

6. Gibbons SGT 2007 Assessment and

rehabilitation of the stability function of psoas

major. Manuelle Therapie. 11:177-18

References

1. Travel and Simons. Myofascial Pain and

Dysfunction. The Lower Extremities (Volume 2).

Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Philadelphia.

2. Sports Med. 1998; 25(4):271–283

3. Spine. 1998; 23(8):928-931

4. Spine. 2008; 33(26): E983–E989.

5. Spine. 1994; 19(2):165-172

6. Gibbons SGT 2007 Assessment and

rehabilitation of the stability function of psoas

major. Manuelle Therapie. 11:177-18