Hyperextension knee injuries can differ from chronic to acute, depending on their severity, and these

are generally considered quite painful. The infrapatellar fat pad, abbreviated as IPFP, is one

of the most commonly affected structures due to hyperextension knee injuries.

In the presence of an acute knee hyperextension injury, for example, when an

athlete is tackled in rugby, the posterior cruciate ligament, or PCL and/or the

posterior lateral corner, or PLC, of the knee may become injured.

Infrapatellar Fat Pad

Anatomy

The

infrapatellar fat pad is identified as an extrasynovial structure which is

located on the anterior of the knee, away from the area of the patella. It’s

characterized as a mobile formation and its shape, volume and pressure is

altered with the movement of the knee. The infrapatellar fat pad attaches

anteriorly to the immediate patellar tendon and inferior pole of the patella,

posteriorly attaching to the intercondylar notch of the femur and in some

individuals, the ACL. It is a heavily vascularized structure, also innervated

by branches of the obturator, saphenous and the well-known peroneal nerve. The

fibres which denote pain from the stimulation of the nerve cells are most dense

in the central and lateral sections of the infrapatellar fat pad.

Mechanism of Injury

Injuries or

conditions affecting the infrapatellar fat pad may commonly result from a direct

blow or as a result of chronic irritation due to hyperextension knee injuries.

Both conditions present a series of painful symptoms which can be debilitating.

Individuals or athletes with these types of complications experience knees that

hyperextend and they may walk with poor quad control and knee hyperextension. The

IPFP, or infrapatellar fat pad, can also become injured as a result of direct

trauma to the knee, either through a blunt force or through shear injury along

with a patellar dislocation or ACL rupture.

Assessment

Individuals with hyperextension knee injuries

originating from infrapatellar fat pad issues often describe a sharp, burning

and/or aching deep pain on either side of the patellar tendon. Certain sports

or physical activities, including maximal knee extensions or basic activities

which require active knee extension, such as going upstairs or prolonged knee

flexion, may aggravate the symptoms of hyperextension knee injuries from the

IPFP.

Healthcare professionals may perform various clinical tests to diagnose

and set apart infrapatellar fat pad complications from other hyperextension

knee injuries.

Upon medical assessments, patients with IPFP disorders frequently

present swelling and inflammation along the bottom of the patella, displaying

the appearance of puffy knees.

Objective tests include: Hoffa’s test, performed where the infrapatellar

fat pad is palpated on either side of the patella tendon, with the knee in a

30-degree flexion. The knee is then fully and passively extended where

increased pain in the IPFP will indicate a positive test; the passive knee

extension test is performed by having the patient lie supine, where the knee is

passively extended. Pain along the bottom of the patella indicates a positive

test result; the differentiation test, as the name pertains, helps to

distinguish between infrapatellar fat pad and patellar tendon injuries and/or

conditions. Primarily, the location of most tenderness is palpated in 30-degree

knee flexion. The patient is then ordered to gently activate their quadriceps

muscle while the healthcare professional providing the test resists this

movement. The isometric activation of the quadriceps lifts the patellar tendon

off the IPFP, decreasing the symptoms on palpation.

Imaging

MRI is the most common modality of choice for suspected hyperextension

knee injuries to the infrapatellar fat pad. According to the results of an MRI,

increased T1 or T2 hypointense signals may conclude the thickening and scarring

of the connective tissue of the fat pad, also referred to as fibrosis, usually

the result of trauma from an injury. T2 weighted images which display

hypointense signals may demonstrate inflammation or acute hemorrhage or edema.

Treatment

Hyperextension knee injuries caused by disorders of the IPFP effective

respond to conservative treatments. The fundamental goal of treatment is to

reduce the stress and pressure being placed against the fat pad to decrease the

symptoms of pain as well as allow the quadriceps to regain their strength. Infrapatellar

fat pad deloading taping procedures should be taught to the affected

individuals to prevent continuous compression of the fat pad. Limiting the

athlete’s stance and gait must be suggested as early as possible to avoid

hyperextension knee injuries during these activities. Helpful exercises which

can further benefit throughout the rehabilitation process includes wall squats,

splits squats and lunges. Exercises which involve full knee extension should be

avoided. To re-train the muscles, quadriceps strengthening drills should

specifically be performed in closed kinetic chain positions.

Surgical procedures are rarely required but may include fat pad

excision, debridement, synovectomy, infrapatellar plica release and denervation

of the inferior pole of the patella.

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries

The posterior cruciate ligament, or PCL, frequently becomes injured when

the knee is flexed, although, it can also be injured in hyperextension knee

injuries, such as a rugby tackle. Approximately 60 percent of PCL injuries also

affect the posterolateral corner, an increased estimate of injuries are

primarily involved with knee hyperextension.

Anatomy

The posterior cruciate ligament is also an extrasynovial structure which

functions to prevent the posterior shift of the tibia on the femur. It’s made

up of an anterolateral bundle which is most rigid during knee flexion and a

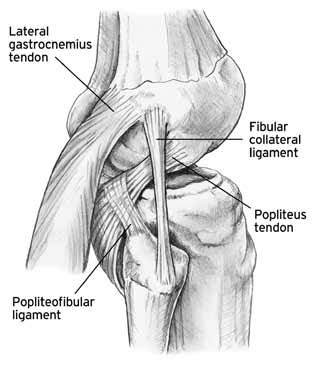

posteromedial bundle which is most rigid in extension. The posterolateral

corner consists of the popliteus muscle, the lateral collateral ligament, bicep

femoris tendons and the popliteofibular ligament. Isolated injuries to the

posterior cruciate ligament are rare but may be often associated with PCL

complications.

Assessment

Through diagnosis and evaluation of individuals or athletes with

posterior cruciate ligament injuries have been recorded with poorly defined

knee pain along with minimal swelling. Various assessments are utilized to

conclude the presence of injury to the PCL, including: posterior drawer, a test

which comprises of having the patient lying supine with the affected knee bent

to 90-degrees. The position of the tibia relative to the femur is recognized

and recorded by the healthcare professional providing the assessment, where a

posterior-positioned tibia indicates the presence of a posterior cruciate

ligament injury; with the posterior sag test, the patient lies supine with

their hips flexed to 90-degrees and their knees bent to 90-degrees as well. The

healthcare professional then supports under the lower calf of both legs,

looking for a posterior sag of the tibia; and finally, the quad contraction

test is used in the case that a posterior tibial translation is suspected while

the patient is supine and their knees are bent to 90-degrees. To perform this

test, the medical specialist holds the lower shin and asks the patient to

contract their quads. If a posterior sag is present, then, contraction of the

quadriceps will lead to an anterior shift of the tibia.

Posterior cruciate ligament injuries are classified from 1 to 3 and are preferably

measured with the knee in 90-degree flexion where the tibia normally lies 1 cm

anterior to the femoral condyles. The grading system is outlined as follows: G1,

where the tibia lies anteriorly to the femoral condyles, however, the distance

is reduced to 0-5mm; G2, where the tibia lies flush with the condyles; and G3,

where the tibia can be pushed beyond the medial femoral condyle.

As previously mentioned, injuries to the posterolateral corner may also

develop with the presence of an injury to the PCL, such as in the case of

hyperextension knee injuries. Various evaluation tests are characterized to

help determine whether a posterolateral corner injury is present, including:

the external rotation recurvatum, or hyperextension, test, performed where the

patient lies supine and the healthcare professional stabilizes the distal thigh

with one hand while lifting the great toe with the other. If the specialist

recognizes more hyperextension in the affected knee, then, a posterolateral corner

injury can be concluded; to perform the dial test, the patient must lie prone

with the knees flexed to 30-degrees. The healthcare professional then

externally rotates the tibia of both legs, making sure the thighs maintain a

stabilized position. A greater range of external rotation of more than

10-degrees represents a positive test result. This test can also be performed

with the knees flexed at 90-degrees and in the case of increased range, then, a

combined injury to the posterior cruciate ligament and PLC injuries are

suspected.

Gait evaluations should also be performed. Patients whom result with

instability on the posterolateral corner present varus gait at foot strike when

their knee is extended.

Imaging

Posterior cruciate ligament and posterior lateral corner injuries

commonly result due to an acute injury. In the case of a considerable acute

injury, X-rays may be requested to exclude the presence of a bony avulsion of

the PCL from its tibial insertion. If so, surgical intervention may be

necessary to repair this type of injury. MRI scans may also be useful in this

instance to help determine the presence of posterior cruciate ligament and

posterior lateral corner injuries.

Treatment

According to various treatment results, individuals and athletes with

isolated posterior cruciate ligament tears or ruptures experience an effective

functional outcome through a properly designed rehabilitation program, despite

of ongoing laxity. However, research studies have concluded that PCL

deficiencies do occur during increased pressure within the joints on both the

patellofemoral tibiofemoral joints. This may therefore indicate that meniscal

tears and articular damage to the medial compartments of the knee, may develop

gradually over time. If PCL injuries occur conjointly with the damage of other

structures of the knee, including PLC, or whether a considerable instability is

found, surgical interventions should be considered. An individual with a grade

3 PCL injury is recommended to participate in immobilized extensions for up to

two weeks. An individual with a grade 1 to 2 injury is recommended to

participate in a specific rehabilitation program with a focus on strengthening the

quadriceps.

Do You Need Surgery for a PCL Injury?

Many healthcare professionals specialize in the diagnosis and

rehabilitation of a variety of sports injuries, including hyperextension knee

injuries. Chiropractic care is a popular, alternative treatment option which

emphasizes on the overall health of the body through the proper alignment of

the spine and its surrounding structures, including the muscles, ligaments,

tendons, joints and other essential tissues. Chiropractors are also specialized

in evaluating many types of sports injuries. Once a doctor of chiropractic, or

DC, determines the presence and origin of an individual’s symptoms, they

commonly utilize a series of chiropractic adjustments to reduce the stress and

pressure around the complex structures of the injury, helping to decrease the

athlete’s pain and discomfort. Along with several other types of treatment

options, a chiropractor may also recommend a course of rehabilitation stretches

and exercises to improve an individual’s original strength, flexibility and

mobility as well as speed up the rehabilitation process.

Before engaging in a rehabilitation program, the individual or

athlete must primarily seek medical attention from a qualified healthcare professional who will follow up with the most appropriate group of exercises according to each individual’s grade of injury and needs. Advancing with a rehabilitation program will be commonly determined by the patient’s improved symptoms and therefore, should only be modified

by the specialist to avoid further injury.

By Dr. Alex Jimenez