Medial tibial stress syndrome, commonly referred to as shin splints, is

not considered to be a medically serious condition, however, it can challenge

an athlete’s performance. Approximately 5 percent of all sports injuries are

diagnosed as medial tibial stress syndrome, or MTSS for short.

|

| Share Free Ebook |

Shin splints, or MTSS, occurs most frequently in specific groups of the

athletic population, accounting for 13-20 percent of injuries in runners and up

to 35 percent in military service members. Medial tibial stress syndrome is

characterized as pain along the posterior-medial border of the lower half of

the tibia, which is active during exercise and generally inactive during rest.

Athletes describe feeling discomfort along the lower front half of the leg or

shin. Palpation along the medial tibia can usually recreate the pain.

Causes of MTSS

There are two main speculated causes for medial tibial stress syndrome.

The first is that contracting leg muscles place a repeated strain upon the

medial portion of the tibia, producing inflammation of the periosteal outer

layer of bone, commonly known as periostitis. While the pain of a shin splint

is felt along the anterior leg, the muscles located around this region are the

posterior calf muscles. The tibialis posterior, flexor digitorum longus, and

the soleus all emerge from the posterior-medial section of the proximal half of

the tibia. As a result, the traction force from these muscles on the tibia

probably aren’t the cause of the pain generally experienced on the distal

portion of the leg.

Another theory of this tension is that the deep crural fascia, or the

DCF, the tough, connective tissue which surrounds the deep posterior muscles of

the leg, may pull excessively on the tibia, causing trauma to the bone.

Researchers at the University of Honolulu evaluated a single leg from 5 male

and 11 female adult cadavers. Through the study, they confirmed that in these

specimens, the muscles of the posterior section of muscles was introduced above

the portion of the leg that is usually painful in medial tibial stress syndrome

and the deep crural fascia did indeed attach on the entire length of the medial

tibia.

Doctors at the Swedish Medical Centre in Seattle, Washington believed

that, given the anatomy, the tension from the posterior calf muscles could produce

a similar strain on the tibia at the insertion of the DCF, causing injury.

In a laboratory study conducted using three fresh cadaver specimens,

researchers concluded that strain at the insertion site of the DCF along the

medial tibia advanced linearly as tension increased in the posterior leg muscles.

The study confirmed that an injury caused by tension at the medial tibia was

possible. However, studies of bone periosteum on individuals with MTSS have yet

to find inflammatory indicators to confirm the periostitis theory.

The second theory believed to cause medial tibial stress syndrome is

that repetitive or excessive loading may cause a bone-stress reaction in the

tibia. When the tibia is unable to properly bear the load being applied against

it, it will bend during weight bearing. The overload results in micro damage

within the bone, not just along the outer layer. If the repetitive loading

exceeds the bone’s ability to repair, localized osteopenia can occur. Because

of this, some researchers consider a tibial stress fracture to be the result of

a continuum of bone stress reactions that include MTSS.

Utilizing magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, on the affected leg can often

display bone marrow edema, periosteal lifting, and areas of increased bony

resorption in athletes with medial tibial stress syndrome. This supports the

bone-stress reaction theory. An MRI of an athlete with a diagnosis of MTSS can

also help rule out other causes of lower leg pain, such as a tibial stress

fracture, deep posterior compartment syndrome, and popliteal artery entrapment

syndrome.

Risk factors for MTSS

While the cause, set of causes or manner of causation of MTSS is still

only a hypothesis, the risk factors for athletes developing it are well-known. As

determined by the navicular drop test, or NDT, a large navicular drop

considerably corresponds with a diagnosis of medial tibial stress syndrome. The

NDT measures the difference in height position of the navicular bone, from a

neutral subtalar joint position in supported non-weight bearing, to full weight

bearing. The NDT explains the degree of arch collapse during weight bearing.

Results of more than 10 mm is considered excessive and can be a considerable risk

factor for the development of MTSS.

Research studies have proposed that athletes with MTSS are most

frequently female, have a higher BMI, less running experience, and a previous

history of MTSS. Running kinematics for females can be different from that of

males and has often been demonstrated to leave individuals vulnerable to suffer

anterior cruciate ligament tears and patellofemoral pain syndrome. This same

biomechanical pattern may also incline females to develop medial tibial stress

syndrome. Hormonal considerations and low bone density are believed to be

contributing factors, increasing the risk of MTSS in the female athlete as

well.

A higher BMI in an athlete demonstrates that they have more muscle mass

rather than being overweight. The end result, however, is the same in that the

legs bear a considerably heavy load. It’s been hypothesized that in these

cases, the bone growth accelerated by the tibial bowing may not advance quickly

enough and injury to the bone may occur. Therefore, those with a higher BMI may

need to continue their training programs gradually in order to allow the body

to adapt accordingly.

Athletes with less running experience are more likely to make training

errors, which may be a common cause for medial tibial stress syndrome. These

include but are not limited to: increasing distance too quickly, changing

terrain, overtraining, poor equipment or footwear, etc. Inexperience may also

lead the athlete to return to activity before the recommended time, accounting

for the higher prevalence of MTSS in those who had previously experienced MTSS.

A complete recovery from MTSS can take from six months up to ten months, and if

the original injury does not properly heal or the athlete returns to training

too soon, chances are, their pain and symptoms may return promptly.

Biomechanical Analysis

The NDT is used as a measurable indication of foot pronation. Pronation

is described as a tri-planar movement consisting of eversion at the hindfoot,

abduction of the forefoot and dorsiflexion of the ankle. Pronation is a normal

movement of the body and it is absolutely essential in walking and running.

When the foot impacts the ground at the initial contact phase of running, the

foot begins to pronate and the joints of the foot acquire a loose-packed

position. This flexibility helps the foot absorb ground reaction forces.

During the loading response phase, the foot further pronates, reaching

peak pronation by approximately 40 percent during stance phase. In mid stance,

the foot moves out of pronation and back to a neutral position. During terminal

stance, the foot supinates, moving the joints into a fastened position, creating

a rigid lever arm from which to generate the forces for toe off.

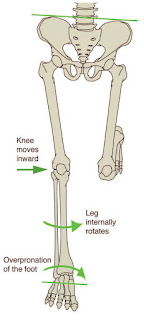

Starting with the loading response phase and throughout the rest of the

single leg stance phase of running, the hip is stabilized and supported as it is

extended, abducted and externally rotated by the concentric contraction of the

hip muscles of the stance leg, including the gluteals, piriformis, obturator

internus, superior gemellus and inferior gemellus. Weakness or fatigue in any

of these muscles can develop an internal rotation of the femur, adduction of

the knee, internal rotation of the tibia, and over-pronation. Overpronation

therefore, can be a result of muscle weakness or fatigue. If this is the case,

the athlete may have a completely normal NDT and yet, when the hip muscles

don’t function as needed, these can overpronate.

In a runner who has considerable overpronation, the foot may continue to

pronate into mid stance, resulting in a delayed supination response, causing

for there to be less power generation at toe off. The athlete can make the

effort to apply two biomechanical fixes here that could contribute to the

development of MTSS. First of all, the tibialis posterior will strain to

prevent the overpronation. This can add tension to the DCF and strain the

medial tibia. Second, the gastroc-soleus complex will contract more forcefully

at toe off to improve the generation of power. However, it’s hypothesized that

the increased force within these muscle groups can add further tension to the

medial tibia through the DCF and possibly irritate the periosteum.

Evaluating Injury in Athletes

Once understood that overpronation is one of the leading risk factors

for medial tibial stress syndrome, the athlete should begin their evaluation

slowly and gradually progress through the procedure. Foremost, the NDT must be

performed, making sure if the difference is more than 10mm. Then, it’s

essential to analyze the athlete’s running gait on a treadmill, preferably when

the muscles are fatigued, such as at the end of a training run. Even with a

normal NDT, there may be evidence of overpronation in running.

Next, the athlete’s knee should be evaluated accordingly. The specialist

performing the evaluation should note whether the knee is adducted, whether the

hip is leveled or if either hip is more than 5 degrees from level. These can be

clear indications that there is probably weakness at the hip. Traditional

muscle testing may not reveal the weakness; therefore, functional muscle

testing may be required.

Additionally, it should be observed whether the athlete can perform a

one-legged squat with arms in and arms overhead. The specialist must also note

if the hip drops, the knee adducts and the foot pronates. Furthermore, the

strength of the hip abductors should be tested in side lying, with the hip in a

neutral, extended, and flexed position, making sure the knee is straight. All

three positions with the hip rotated in a neutral position and at end ranges of

external and internal rotation should also be tested. Hip extensions in prone

with the knee straight and bent, in all three positions of hip rotation:

external, neutral and internal can also be analyzed and observed to determine

the presence of medial tibial stress syndrome, or MTSS. The position where a

healthcare professional finds weakness after the evaluation is where the

athlete should begin strengthening activities.

Treating the Kinetic Chain

In the presence of hip weakness, the athlete should begin the strengthening

process by performing isometric exercises in the position of weakness. For

example, if there is weakness during hip abduction with extension, then the

athlete should begin isolated isometrics in this position. Until the muscles consistently

activate isometrically in this position for 3 to 5 sets of 10 to 20 seconds

should the individual progress to adding movement. Once the athlete achieves

this level, begin concentric contractions, in that same position, against

gravity. Some instances are unilateral bridging and side lying abduction.

Eccentric contractions should follow, and then sport specific drills.

In the case that other biomechanical compensations occur, these must

also be addressed accordingly. If the tibialis posterior is also displaying

weakness, the athlete should begin strengthening exercises in that area. If the

calf muscles are tight, a stretching program must be initiated. Utilizing any

modalities possible might be helpful towards the rehabilitation process. Last

but not least, if the ligaments in the foot are over stretches, the athlete

should consider stabilizing footwear. Using a supported shoe for a temporary

period of time during rehabilitation can be helpful to notify the athlete to

embrace new movement patterns.

MTSS and Sciatica

Medial tibial stress syndrome, otherwise known as shin splints,

ultimately is a painful condition that can greatly restrict an athlete’s

ability to walk or run. As mentioned above, several evaluations can be

performed by a healthcare professional to determine the presence of MTSS in an

athlete, however, other conditions aside from shin splints may be causing the

individuals leg pain and hip weakness. That is why it’s important to also visit

additional specialists to ensure the athlete has received the correct diagnosis

for their injuries or conditions.

Sciatica is best referred to as a set of symptoms that originate from the

lower back and is caused by an irritation of the sciatic nerve. The sciatic

nerve is the single, largest nerve in the human body, communicating with many

different areas of the upper and lower leg. Because leg pain can occur without

the presence of low back pain, an athlete’s medial tibial stress syndrome could

really be sciatica originating from the back. Most commonly, MTSS can be

characterized by pain that is generally worse when walking or running while

sciatica is generally worse when sitting with an improper posture.

Regardless of the symptoms, it’s essential for an athlete to seek proper

diagnosis to determine the cause of their pain and discomfort. Chiropractic

care is a popular form of alternative treatment which focuses on

musculoskeletal injuries and conditions as well as nervous system disorders. A

chiropractor can help diagnose an athlete’s MTSS as well as overrule the

presence of sciatica as a cause of the symptoms. In addition, chiropractic care

can help restore and improve an athlete’s performance. By utilizing careful

spinal adjustments and manual manipulations, a chiropractor can help strengthen

the structures of the body and increase the individual’s mobility and

flexibility. After suffering an injury, an athlete should receive the proper

care and treatment they need and require to return to their specific sport

activity as soon as possible.

Chiropractic and Athletic Performance

In conclusion, the best way to prevent pain from MTSS is to decrease the athlete’s risk

factors. An athlete should have a basic running gait analysis and proper shoe

fitting as well as include hip strengthening in functional positions as part of

the strengthening program. Furthermore, one must ensure the athletes fully

rehabilitate before returning to play because the chances of recurrence of

medial tibial stress syndrome can be high.

By Dr. Alex Jimenez