Headaches are a highly common afflicting, affecting approximately 66

percent of the general population, causing pain and discomfort which alters an

individual’s quality of life and work rate. Up to fourteen various forms of

headaches have been previously recorded by The International Headache Society.

Particularly, the classification of headache disorders can be greatly

beneficial when diagnosing an individual’s cause of headache.

The IHS classification of headache disorders can be categorized as

follows:

The primary types of headache disorders include, headaches without a

seemingly identifiable cause, for example, tension-type headaches, or TTH,

migraines, chronic daily headaches, medication overuse headaches and trigeminal

autonomic cephalagia, or cluster headache. The secondary types of headache

disorders include, headaches associated with secondary pathologies, for

example, cervicogenic headaches, TMJ, infection, brain tumors and stroke.

Cranial neuropathies, facial pains and other types of headache disorders

include, headaches related to neural disorders of the head and neck, for

example, trigeminal neuralgia.

Since each form of headache has a different pathological foundation and

because an incorrect differential diagnosis will often lead to treatment

failure, it is essential to properly diagnose the type of headache. This is of

particular importance for manual therapy interventions, alternatively, they are

unlikely to be effective for the majority of headache forms. When considering

the best clinical approach to athletes experiencing symptoms of headache, there

is a helpful tool, which can be utilized when contemplating the appropriate

management pathway.

Function of the Trigeminocervical Nucleus

(TCN)

The most

common form of headaches are tension-type headaches, or TTH, affecting up to 38

percent of individuals globally, as compared to migraines, which affect up to

10 percent of the population, chronic daily headaches, affecting 3 percent and

cervicogenic headaches, which affect from 2.5 to 4.1 percent of individuals. Cervicogenic

headaches primarily originate as a result of musculoskeletal dysfunction in the

upper three cervical sections. The prevalence is as high as 53 percent in the

general population or athletes with headache symptoms after experiencing

whiplash-associated trauma.

The mechanism underlying the pain involves the union between cervical

and trigeminal afferent nerve fibers or vessels in the trigeminocervical

nucleus, which travels down the spinal cord to the level of the vertebrae

segments, C3 and C4, in the cervical spine.

The trigeminocervical nucleus has anatomical and functional progression

with the dorsal grey columns of these spinal regions. For that reason, input

through a sensory afferent, particularly from any of the upper three cervical

nerve roots, may be incorrectly perceived as pain in the head, a concept best

referred to as convergence.

Convergence between cervical afferent nerve fibers or vessels, allows for

upper cervical pain to be guided to regions of the head innervated by cervical

nerves, including the occipital and auricular regions. Nonetheless, combining with

trigeminal afferents provides a standard guideline into the parietal, frontal,

and orbital regions. This can cause confusion when diagnosing the cause of

headaches.

Differentiating Headaches

Medically distinguishing the different forms of headache can be

challenging. The subjective information is absolutely crucial.

The following diagnostic criteria have been proposed by the Cervicogenic

Headache International Study Group as follows:

The signs and symptoms of neck involvement as a cause of headaches

includes the precipitation of headache by neck movement, postural changes

and/or pressure over the upper cervical/occipital region, along with the

restriction of neck range of motion, or ROM and the presence of ipsilateral

neck, shoulder or vague arm pain.

Head pain characteristics are described as moderate to severe,

non-throbbing and non-clustering, starting in the neck and spreading to the

head. These can have a varying duration and generally last longer than a

migraine headache with a long-term fluctuating pattern, becoming continuous

when chronic. As for migraines, these can occur most frequently on females, identified

by symptoms of nausea, photophobia and throbbing pain, following a crescendo

pattern.

Diagnosis is based on these subjective features as well as a physical

examination of articular, neural, and myogenic systems while understanding the

mechanisms of the symptoms. Exclusion of red and yellow flags at this stage is

also essential. There can be many structural causes of cervicogenic headaches.

The potential causes of cervicogenic headaches includes: psychosocial

co-morbidities, such as depression and anxiety, along with reported dysfunction

in the joints, muscles, neural tissues, vascular structures and others such as

damage or injury to the temporomandibular joint.

Assessing Cervicogenic Headaches

The goal of the assessment is to reproduce the pain of headache from the

structures surrounding the cervical spine with evidence of an associated

dysfunction. By assessing the articular, neural, and muscular structures during

the evaluation, one can be certain that the source of the individual’s

cervicogenic headaches can be found. Subsequently, if pain cannot be

reproduced, then the involvement of the cervical spine can be dismissed and

other causes of headaches will need further evaluation.

The prevalence of neural tissue pain disorders has been proclaimed among

7 to 10 percent of individuals with cervicogenic headaches. In this case, pain

reproduction can be used as a tool to distinguish neural tissue involvement

when evaluating posture, upper cervical active range of motion, neural

provocation tests combined with upper cervical range of motion, nerve palpation

and neurological examination. In the same manner, if the presence of vascular

involvement is suspected, a clinical framework can be suggested to allow an

accurate guideline for assessment and management, primarily focusing on the

diagnosis and treatment of cervicogenic headaches with articular cause.

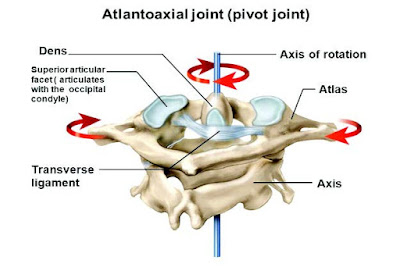

Trauma involving forced cervical flexion, rotation, or side flexion is

very common in sports and physical activities. Similar to testing ligament

stability in the knee joint following trauma, screening for craniovertebral

instability should be prevalent in the assessment.

The Sharp Purser (Transverse Ligament) Test

When screening for craniovertebral instability, it's essential to observe that these tests are most appropriate for diagnosing cervical imbalances. Healthcare specialists must remain aware that other cervical-related complications can also cause pain, such as facet joint disorders, therefore, these should also be assessed accordingly.

To perform this test, the individual must be in a sitting position where the healthcare professional will proceed to place the base of their index finger over the C2 spinous process. The upper cervical spine is flexed. There will be an attempt to translate the affected individual's head posteriorly with the C2 fixed. A positive test is demonstrated by a change in symptoms; a clunk sensation and/or movement of the C1 back towards the index finger on C2.

The Tectorial Membrane (Posterior Longitudinal Ligament) Test

To perform this test, while the individual is sitting, a healthcare

professional will craddle the occiput and head. Fixing the C2 spinous process with

the base of the index finger in a downward directio. The direction of force is

an axial distraction one, attempting to lift the head up on the neck to

separate the two. Normal distraction should not exceed 1-2 mm.

Alar Ligament Test

For this test, in sitting, the individual or athlete’s head will be

craddled while the bific spinous process of the C2 is fixed with the index

fingeer and the thumb. Side flexion down to the C2 is performed by moving the

individual’s head. Any movement of the head without movement of the C2 spinous

process indicates laxity of the alar ligament complex and a positive test.

Flexion/Rotation

The C1-C2 motion segments of the cervical spine accounts for 50 percent

of the rotation in the cervical spine. Therefore, pain originating from an

impairment of this region is a common finding in individuals with cervicogenic

headaches. The flexion-rotation test, or FRT, is an easily applied clinical

test developed to identify dysfunction at the C1-C2 motion segment of the spine.

The Average flexion-rotation test results of the range of motion in the neck of

healthy individuals is 44 degrees. The test is positive if there is pain or

restriction at 10 degrees in the range of motion of the neck on either side.

Due to the lack of intervertebral disc and altered biomechanics of the

high cervical spine, combined movements are assessed differently. The primary

movement available at C0-C1 is flexion and extension at 3 degrees, with the

majority of movement occurring in extension at 21 degrees. Due to the sliding

movement of the occipital condyles, flexion will stress the posterior capsules

on the right and the left at C0-C1. The addition of ipsilateral rotation will

add further pressure to the posterior capsule on the same side. This can be a

nice diagnostic tool for assessing the involvement of C0-C1 as a cause for

cervicogenic headaches.

C0-C1 Flexion/Rotation Assessment

In order for the individual to stretch the right posterior capsule, the

healthcare professional must first stand on the right of the patient and fix

the mandible with their right hand while the left hand supports the occiput.

Then, the specialist should retract into upper cervical flexion and add

rotation using both hands. The goal is pain provocation.

In comparison, upper cervical extensions can stress the anterior

capsules of the C0-C1. The addition of contra-lateral rotation will place

additional pressure to the anterior capsule on the opposite side of the

movement.

C0-C1 Extension/Rotation Test

To stretch the right anterior capsule, the healthcare specialist must

previously be standing on the right of the individual being tested, using the

right elbow, the test will begin by fixing the individual’s trunk. Grasping the

mandible with the right hand to control the head with the left. Protract into

upper cervical extension, followed by left rotation using both hands. The goal

is pain provocation.

Treating Cervicogenic Headaches

Supporting

evidence has suggested that manual therapies are effective for cervicogenic

headaches, specifically spinal adjustments and manipulation from qualified

healthcare professionals, such as a chiropractor, including mobilization

techniques with exercise. This is particularly accurate for cranio-cervical

muscle strengthening and scapula positional re-training. However, further

research is required to determine the effectiveness of manual therapy for

headaches associated with migraines. Several effective treatments and therapy

techniques for cervicogenic headaches can be utilized to relieve the symptoms

of head pain as follows.

Headache Sustained Natural Apophyseal Glide (SNAG)

For a healthcare professional to perform this test, the specialist will

stand by the affected individual’s side and stabilize the head with their right

hand. The little finger is placed on the posterior aspect of the spinous

process of C2. Horizontal pressure is applied to the little finger by the

thenar eminence of the opposite hand along the upper cervical facet plane. This

must be sustained for 10 seconds and repeated 6 times. Pain should be reduced

during this procedure.

Intermittent Pain: C1-C2 Self-SNAG

If the restriction of pain occurs with a right rotation, the strap can

be placed on the posterior arch of the C1 on the left side precisely below the

mastoid process. The left hand will secure the strap and the right hand will

pull on the strap to force rotation at the C1-C2 motion regions. Repeat this

test twice, two times a day.

Intermittent Pain: C2-C3 Self-SNAG

If pain develops from below the region of the C2, then, a different form

of SNAG may be utilized. In this case, the facet plane is towards the affected

individual’s eyes, approximately 45 degrees. The towel edge can be used if a

strap is not accessible. Sustain for 20 seconds, repeat 6 times.

Cervicogenic Headaches and Chiropractic

If a healthcare professional suspects trigeminocervical nucleus

sensitivity, studies have demonstrated that properly managing sleep, stress and

anxiety as well as following a balanced diet with moderate intensity exercise,

can be beneficial for the individual’s specific type of headache. To help those

affected by the dysfunction understand the concept of trigeminocervical

nucleus, or TCN, sensitization, a bucket analogy can describe the concept. When

the trigeminocervical nucleus is overloaded with data, this is similar to a

bucket being overfilled with water. When the TCN receives too much information

at once, the bucket overflows, hence, causing they symptoms of a headache. If

an athlete can control the level of incoming information, they can control the

level of trigeminocervical nucleus sensitization.

Treatment relies on the diagnostic criteria, but where appropriate,

alternative treatment options, such as chiropractic care, can be beneficial to

assess and treat headaches, including cervicogenic headaches. In particular,

manual therapy has good evidence to support its foundation in treating and

managing cervicogenic headaches. Chiropractic care focuses on musculoskeletal

injuries and conditions, including dysfunction of the nervous system. With the

use of chiropractic adjustments, a chiropractor can carefully re-align the

structures of the spine, helping to reduce the pressure of the tissues as a

result of irritation and swelling, ultimately improving the individual’s

symptoms.

Before treatment however, the athlete should always be aware of vascular

involvement and test for craniovertebral instability, particularly after trauma

in specific sports and physical activities.

By Dr. Alex Jimenez