Injury chiropractic scientist, Dr. Alexander Jimenez looks at how knees can be hyperextended and hurt during sport -- and the way they can be treated.

Knee hyperextension injures could be chronic or acute in their presentation and are often very painful. Structures that are most frequently injured because of knee hyperextension are the infrapatella fat pad (IPFP) or in the event of an acute hyperextension injury (for example when being handled in rugby) trauma to the anterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and/or the posterior lateral corner (PLC) of the knee. This article will talk about both chronic and acute hyperextension injuries of the knee. Additionally, it will outline the anatomy of this infrapatella fat pad, the PCL and the posterolateral corner (PLC). Injury mechanics will be discussed in addition to treatment options.

Infrapatella Fat Pad

Anatomy

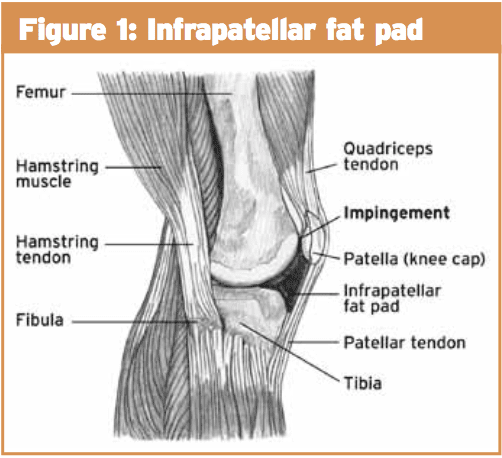

The infrapatella fat pad is an extrasynovial structure which sits on the anterior aspect of the knee only distal to the patella. It is portable and its form, pressure and quantity all alter with knee movement(two) It is attached anteriorly to the proximal aspect of the patella tendon and inferior pole of the patella and posteriorly it attaches to the intercondylar notch of the femur and in some people the ACL(2) (see Figure 1).Mechanism Of Injury

Both of these conditions can be quite painful and debilitating. These customers will frequently have knees that hyperextend and may walk with inadequate quad core control and knee hyperextension. The IPFP can also be injured by trauma to the knee. This may either be through blunt effect or through shear injury with a patella dislocation or ACL rupture. Iatrogenic causes also have been clarified as a result of location of arthroscopy portals and possible for fibrosis.Assessment

On evaluation a patient with a disorder of the IPFP will often clarify a sharp, burning and or aching pain profound and on each side of the patella tendon. Pain- provocative activities include maximal knee extension or actions that need active knee extension, moving upstairs or prolonged knee flexion(1).Several clinical evaluations are used to differentially diagnose IPFP disorders from other pathologies about the knee.

Patients with IPFP ailments will often have swelling inferior to the patella and may describe that they have "bloated" knees (see Figure 2).

1) Hoffa’s test: The IPFP is palpated (either side of the patella tendon) with the knee in 30-degree flexion. The knee is then fully extended (passively) and increased pain in the IPFP indicates a positive test (see Figure 3).

3) Differentiation test: This test is to help differentiate between IPFP and patella tendon disorders. The location of most tenderness is palpated in 30-degree knee flexion. Whilst continuing to palpate the location of most tenderness, the patient is then asked to gently activate the quadriceps muscle, and the clinician resists this movement. Isometric activation of the quadriceps “lifts” the patella tendon off the IPFP which would decrease the pain on palpation if the IPFP is the cause of the pain.

Imaging

When imaging is required, MRI is the modality of choice for suspected injuries to the IPFP. Increased T1 or T2 hypointense signals may indicate fibrosis of the fat pad. T2 weighted images that that show hypointense signal may indicate inflammation or acute haemorrhage or oedema.

Treatment

Disorders of the IPFP most commonly respond quite well to traditional therapy. The main goal of treatment is to de-load the fat pad to reduce pain and permit quadriceps strengthening to occur. Fat pad de-loading tape ought to be educated to the patient so continual impingement of the fat pad is prevented (see Figure 4). Both posture and gait retraining should occur early so knee hyperextension is averted during these actions. Muscle retraining ought to be based around quadriceps strengthening exercises particularly in closed kinetic chain rankings. Exercises which can be beneficial in the rehabilitation process include wall squats, splits squats, squats but exercises that involve complete knee extension should be avoided.Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) Injuries

Anatomy

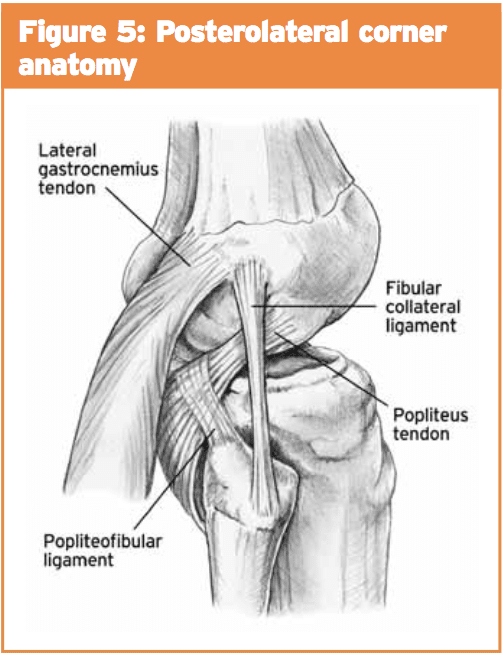

It comprises of an anterolateral bundle which can be most tight in knee flexion and a posteromedial package which is tight in extension(3). The posterolateral corner (PLC) consists of their poplitues muscle, the lateral collateral ligament, bicep femoris tendons along with also the popliteofibular ligament (see Figure 5). Isolated harm to the PLC is rare but is frequently associated with PCL injuries.Assessment

The patient with PCL injury will frequently complain of poorly defined knee pain and often with minimal swelling. Several tests are Utilized to help determine whether harm to the PCL exists:

1) Posterior drawer: This test involves the patient lying supine with the knee bent to 90 degrees. The position of the tibia relative to the femur is noted with posterior-positioned tibia indicative of a PCL injury.

2) Posterior sag: The patient lies supine with hips flexed to 90 degrees and knee bent to 90 degrees. The practitioner supports under the lower calf of both legs and looks for posterior sag of the tibia (see Figure 6).

3) Quad contraction test: If posterior tibial translation is suspected with the patient in supine and the knee bent to 90 degrees. The clinician holds the lower shin and asks the patient to contract quads. If a posterior sag is present then contraction of the quadriceps will lead to anterior translation of the tibia.

2) Posterior sag: The patient lies supine with hips flexed to 90 degrees and knee bent to 90 degrees. The practitioner supports under the lower calf of both legs and looks for posterior sag of the tibia (see Figure 6).

G1: the tibia lies anterior to the femioral condyles but this distance is diminished to 0-5mm;

G2: the tibia lies flush with the condyles;

G3: the tibia can be pushed beyond the medial femoral condyle.

G2: the tibia lies flush with the condyles;

G3: the tibia can be pushed beyond the medial femoral condyle.

As stated before, injuries to the posterolateral corner may also occur with injury to the PCL once the knee is hyperextended. Several tests have been described to help identify if a posterolateral corner injury is present:

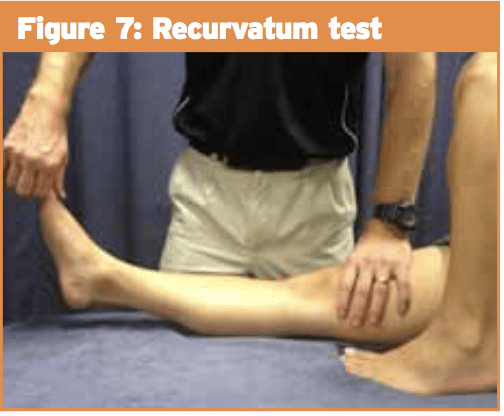

1) External rotation recurvatum (hyperextension) test: The patient lies supine and stabilises the distal thigh with one hand whilst lifting the great toe with the other. If more hyperextension is noted in the affected knee then a posterolateral corner injury is suspected (see Figure 7).

2) Dial test: The patient lies prone with the knees flexed to 30 degrees. The clinician externally rotates the tibia of both legs (ensuring the thighs remain stabilized). An increased range of external rotation of greater than 10 degrees indicates a positive test (see Figure 8). This test can also be done with the knees flexed at 90 degrees and if there is still increased range then a combined injury to the PCL and PLC is suspected.

Imaging

PCL and PLC injuries generally occur in the acute injury. In case of a substantial acute injury x-rays could be warranted to rule out bony avulsion of the PCL from its tibial insertion. If this is present then surgical repair should be undertaken. MRI might again be beneficial to identify PCL and PLC accidents.Treatment

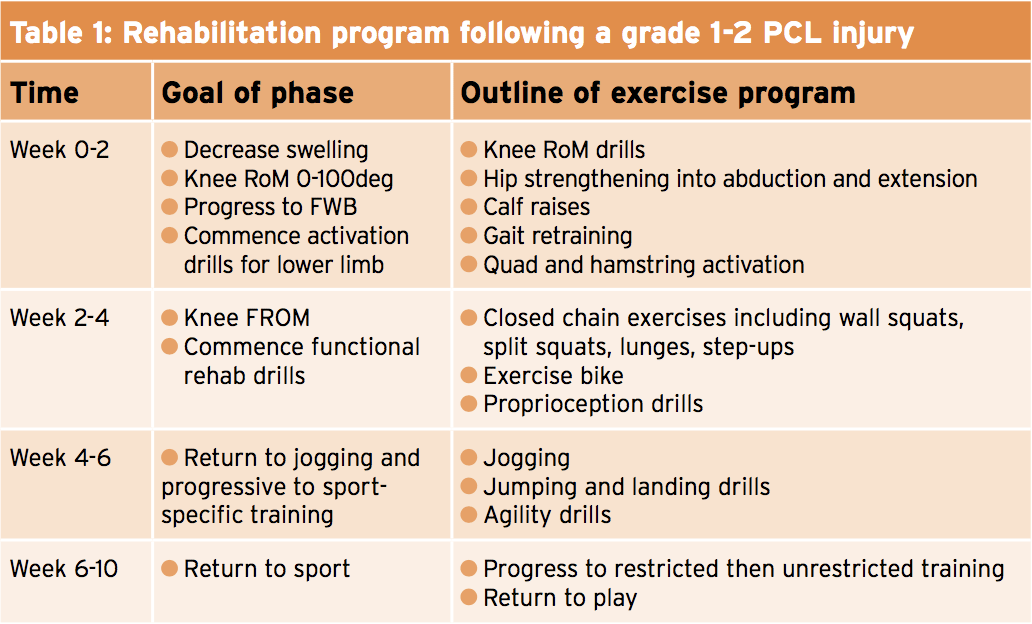

Results reveal that patients with isolated PCL tears have a fantastic functional outcome (even though continuing laxity) with a structured rehabilitation program. The literature does suggest, however, that PCL lack does lead to greater joint contact pressure on both the patellofemoral and tibiofemoral joints. Surgery is indicated if PCL injury happens in combination with other structures (including PLC) or even if important instability exists. If the PCL injury is important (grade 3) then the customer should be immobilized in extension for 2 months(1). If a slight injury (grade 1-2), then a graduated rehab program ought to be commenced with specific emphasis on quadriceps strengthening. Table 1 outlines a rehabilitation program following a regular 1-2 PCL injury. These timeframes should be used as a guide only and progression throughout the rehabilitation program should be decided by the customer's ability as opposed to a predetermined timeframe.Conclusion

Hyperextension injuries at the knee may not occur commonly but may be significant. Unless multiple constructions have been hurt, a well-structured rehab program gives very good results.References

1. Brukner and Khan (2012) Clinical Sports Medicine 4th Edition. McGraw Hill.

2. Dragoo J, Johnson C, McConnell J (2012) Evaluation and treatment of disorders of the infrapatella fat pad. Sports Medicine. 42 (1) 51-67.

3. Grassmayr M, Parker D, Coolican M, Vanwanseele B (2008) Posterior cruciate ligament deficiency: Biomechanical and biological consequences and the outcomes of conservative treatment A systematic review. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 11 433-443.