90% of swimmers will experience shoulder pain at some time in their careers. Chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez examines injury rehabilitation recommendations and, in particular, the demand for an appropriate return to a swimming program in the pool.

Though swimming is a relatively low-risk sport for injury, shoulder pain is common in swimmers. A variety of studies show that over a lifetime, between 40 percent and 91 percent of swimmers will endure a swimming-related shoulder injury(1-4). However, if you think about that elite swimmers might be racking up in the pool every day over 10km, and that the arms would be the prime generators of forward push, we should be surprised. High volume training may result in muscle fatigue of the rotator cuff, upper back, and pectoral muscles, which in turn might lead to micro trauma as a result of reduction of dynamic stabilization of the humeral head(5,6).

Etiology Of Shoulder Injury In Swimmers

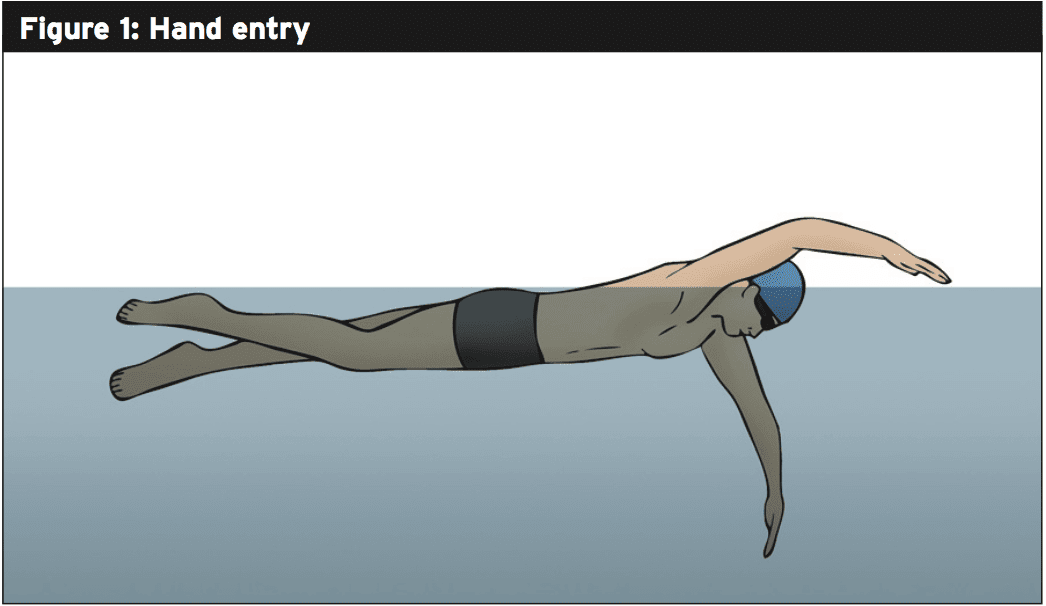

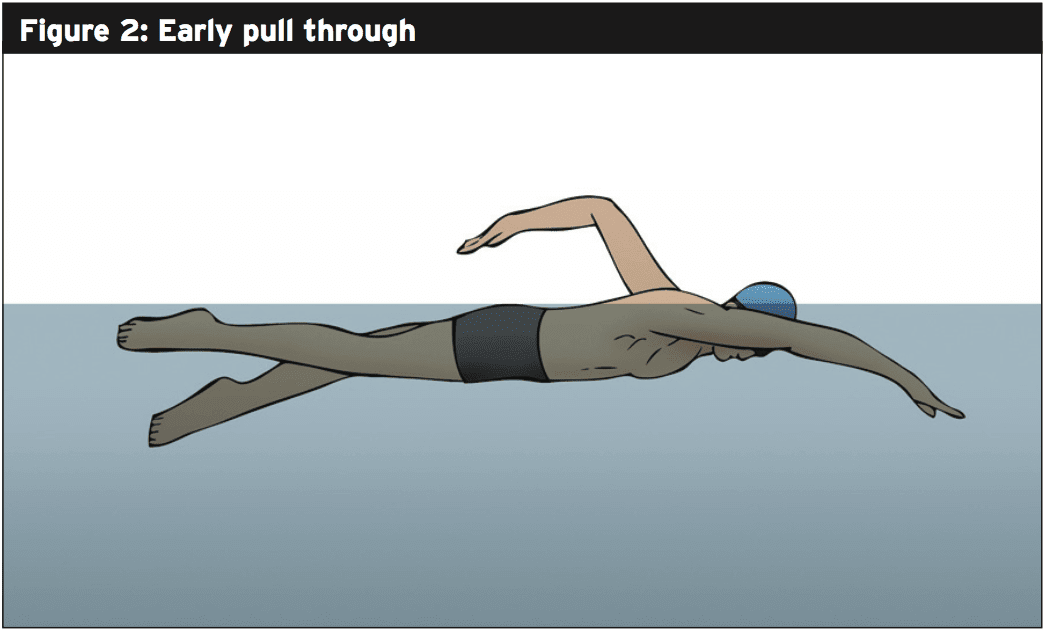

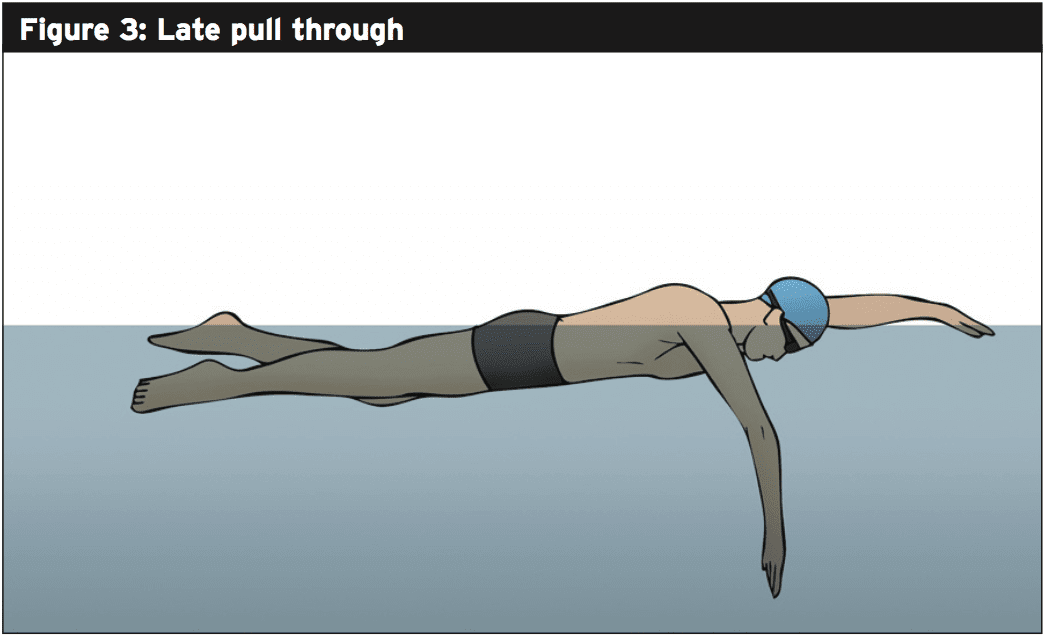

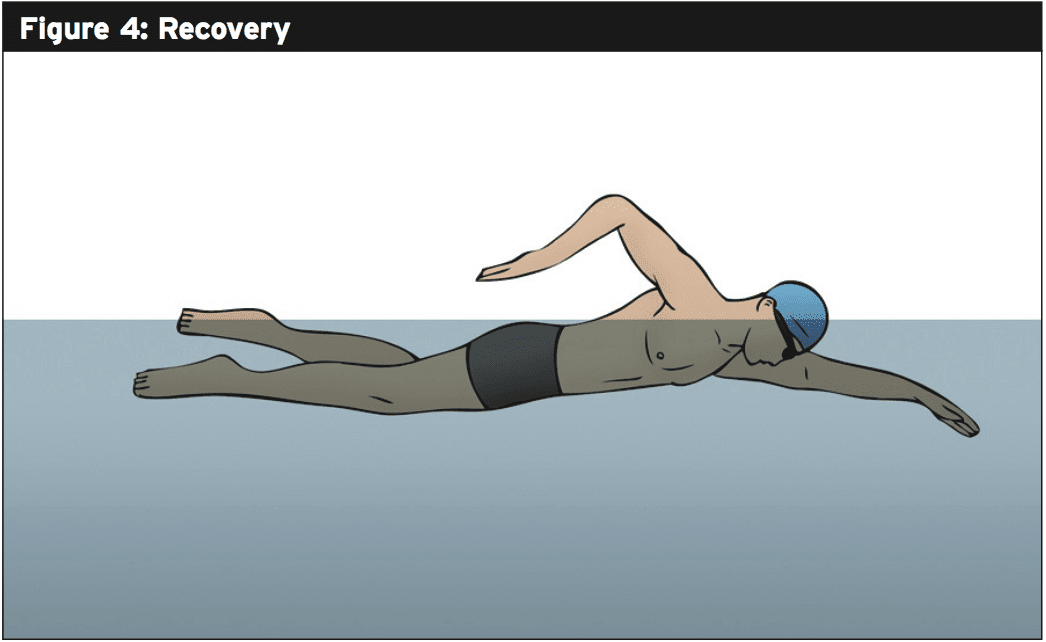

It will help to understand the biomechanics of the stroke cycle, to appreciate the vulnerability of a swimmer’s shoulder to injury. Since freestyle is the most commonly used stroke (for example, the stroke of selection in related sports such as triathlon) we’ll concentrate on this particular style. The stroke contains four distinct phases, which are shown in figures 1-4.In freestyle swimming, each one of these phases has the potential to raise the risk of shoulder injury when executed. Some of the common errors are as follows:

Hand entry — the swimmer’s hand enters the water either medial or lateral to the ideal line (with the swimmer’s head representing 12 o’clock, a right hand should enter the water at approximately 1 o’clock and a left hand at 11 o’clock). A deviation either way increases stress on the rotator cuff.

Land-Based Prevention & Rehab Training

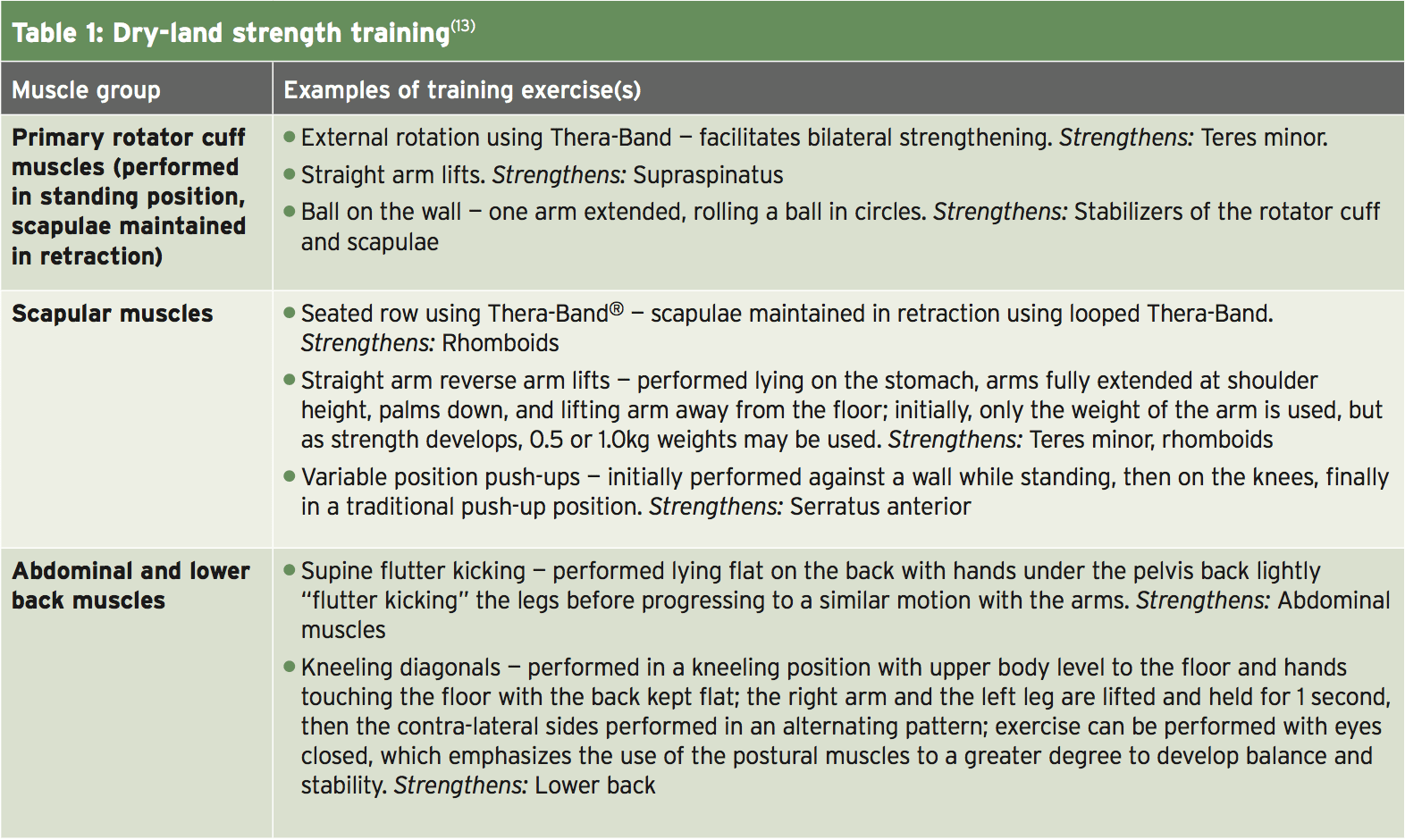

Studies indicate that an endurance training and strengthening program for the shoulder and periscapular muscles, with emphasis placed on the serratus anterior, rhomboids, lower trapezius, and subscapularis, may help prevent injuries and speed recovery when injury does occur(9,10). There’s also evidence that abdominal and scapular muscle strengthening performed in dry-land training can yield benefits; in particular, the goal of core and abdominal strengthening is to develop greater control of the pelvis by avoiding excessive anterior pelvic tilt and lumbar lordosis(11,12). Table 1 shows some example of some commonly-used dry-land training exercises that fulfill these criteria.Returning To Swim Training

Much has been written about land rehab training following shoulder injury and pain management. On the other hand, the return to pain-free swimming training in the water presents a challenge. All too often, symptoms improve or resolve to replicate after rest and dry-land training only when the swimmer is back in the pool. The specific hurdles that need to be overcome at this stage are ironing any stroke imperfections while building up swimming training volume without overload and gradually.There are two criteria that have to be achieved before a return swimming program can be begun by a swimmerthe swimmer be in a position to attain active extension and external rotation of the glenohumeral joint and should be nearly pain free in the shoulder complex. Secondly, the strength of the rotator cuff and scapular stabilizing muscles should be scored at 5/5 when tested using traditional manual muscle testing(14,15).

Dry-land training performed is generally very effective at getting the swimmer. As the predisposing factors to injury may be present, it is important for physiotherapists to appreciate that simply handing the swimmer back to the coach without any additional support or advice risks further setbacks. There is a preferred approach collaboration with the coach to ensure the subsequent training is both measured and appropriate.

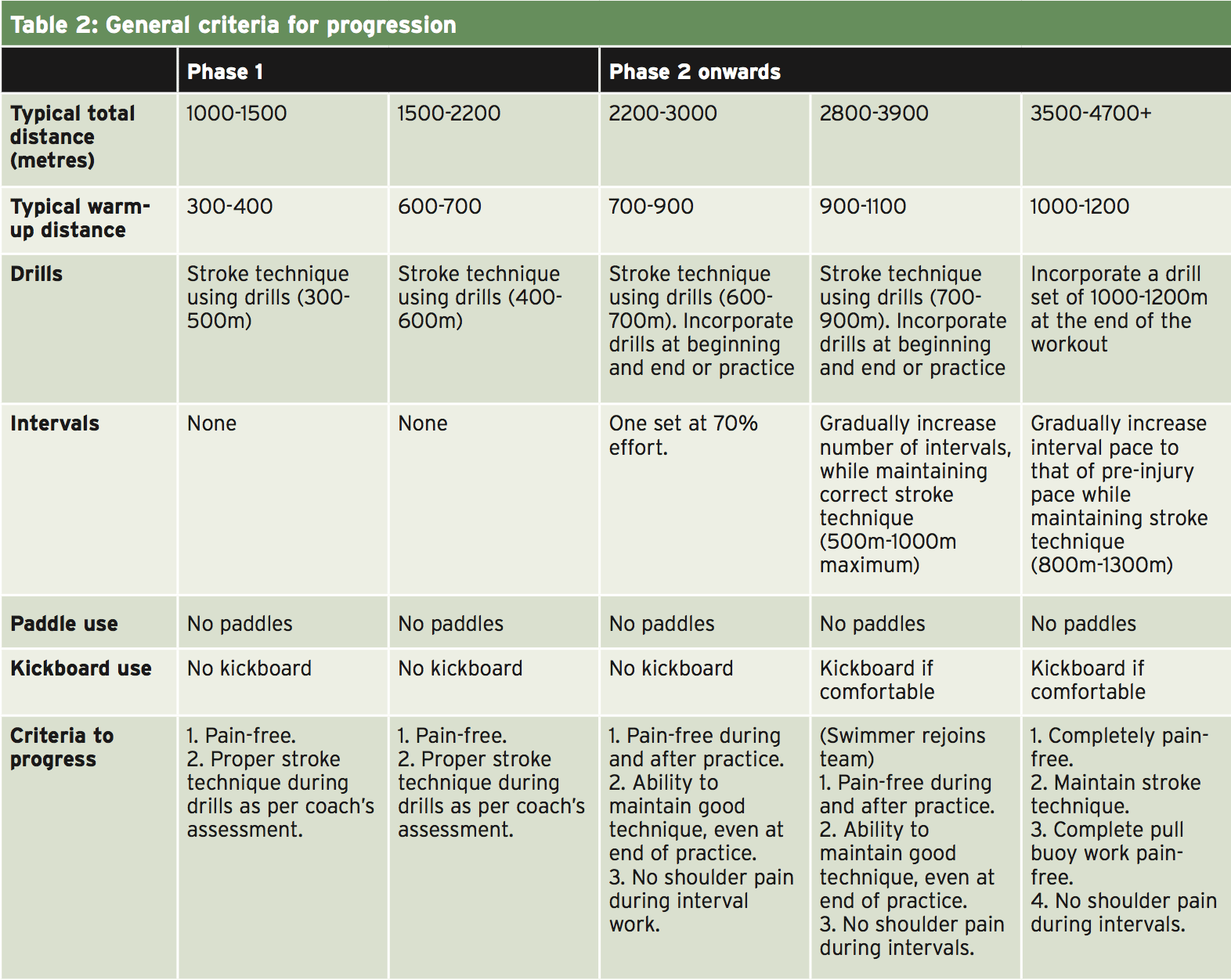

In a recently published paper on this topic, Spigelman et al suggest a two-phase approach(16):

Phase 1 – Focuses on stroke technique drills to protect against the swimmer from reverting. The distance increases only to allow assessment of the shoulder is coping with the resumption of training and to prevent overuse;

Phase 2 – Once the swimmer has successfully completed phase 1, the focus switches to interval work, which is designed to help build the swimmer’s muscular and cardiovascular fitness levels. In this phase distance increases in bigger increments in order to help build endurance — but only if the swimmer can demonstrate she or he can tolerate practices.

What’s important to keep in mind is that a return to swimming program’s objective is to return the swimmer focusing on the swimmer’s speciality stroke or distance isn’t important at this time. When the swimmer can swim reasonable training volumes with technique and without pain should event-specific training be considered.

Communication

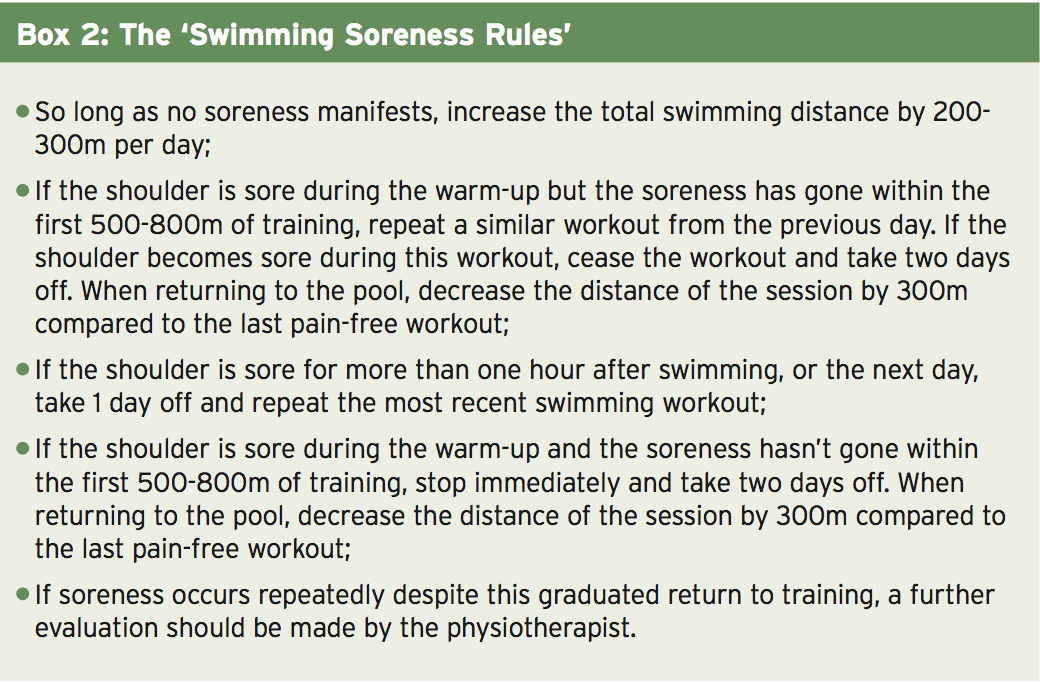

It follows from the above that communication is necessary, both between the swimmer and coach, and between the coach and physiotherapist. The coach should communicate with the swimmer the significance of providing constant feedback about how their shoulder is responding to the increasing training load. It needs to be stressed that any signs of pain or discomfort need to be reported so the coach can pause the training if necessary and evaluate the circumstance. A useful instrument in this regard is the ‘Swimming Soreness Rules’, which can help the swimmer recognize pain, along with the coach/chiropractor adjust the swimming part of shoulder rehab in the swimmer’s program(16). These rules are displayed in Box2.Criteria For Progression

A thorough description of suitable drills and swimming workouts for the swimmer returning to the pool is beyond the scope of this article and will of course depend on the swimmer in question, his/her event, stage of development etc.. On the other hand, the general criteria for progression from phase 1 to phase 2, and from phase 2 to resuming training can be given. A good instance of this in practice is shown in Table 2. It must be emphasized that the swimmer and coach both need to understand that progression should only be very gradual. Any increases in pain, soreness or discomfort have to get recognized by the swimmer and coach as warning signs that are potential to decrease while re-evaluation occurs, or suspend training.Summary

Overuse injuries to the shoulder are all too typical in competitive swimmers, especially where training volumes are high and stroke technique is less than perfect. Evaluation by the clinician, proper and rest strengthening exercises that are dry-land are an important first phase of any recovery program. The process of rehab shouldn’t stop there.The first couple of weeks in the pool as part of a return to swimming program are important for a full recovery, and this is a time when cooperation between the swimmer’s coach and the clinician can be useful. During the return to swimming program, any increase in workload should only be very gradual with an emphasis on correcting any stroke errors as opposed to rushing the swimmer back. A key part of this process is constant feedback from the swimmer and monitoring of that chiropractor and the coach can make any adjustments to the program as needed.

References

1. Clin J Sport Med. 2010;20(5):386-390

2. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(2):254-260

3. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17(4):373-377

4. Clin Sports Med. 1999;18(2):349-359

5. Orthop Clin North Am. 2000;31(2):247-61

6. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(2):105-113

7. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(1):67-70

8. Clin Sports Med.2001;20(3):423-438

9. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(6):569-576

10. Rodeo SA. Swimming. In: Krishnan SG, Hawkins RJ, Warren RF, eds. The Shoulder and the Overhead Athlete. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & WIlkins; 2004:350

11. Phys Sportsmed. 2003;31(1):41-46.

12. Kibler WB, Herring SA, Press JM. Functional Rehabilitation of Sports and Musculoskeletal Injuries. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers; 1998

13. Sports Health. 2012 May;4(3):246-51

14. J Chiropr. 2004;41(10):32-38.

15. Kendall FP, Kendall FP. Muscles : Testing and function with posture and pain. 5th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005

16. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014; vol 9 (5) 712