Chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez explores the advantages of using eccentric strengthening in rehab for a faster Return-to-play following severe hamstring injuries.

Sporting activities involving high demands of sprinting or excessive stretching (kicking, slipping, split positions) are found to affect the incidence of severe hamstring injuries. Hamstring injuries are varied in character comprising differing injury types, location and size. This makes recommendations concerning rehabilitation and prognosis about healing time plus return-to-play notoriously difficult. It’s been suggested that reunite- to-play timescales change between 28-51 days after acute hamstring injuries based upon the biomechanical cause, site, and evaluation of soft tissue injury(1). However, this is a controversial issue, which this report will explore.

After a return to game, the probability of re-injury is high within the first 2 weeks(2). The causes are linked with first hamstring weakness; fatigue; a lack of flexibility, and a strength imbalance between the hamstrings (bizarre) and also the quadriceps (concentric)(2). The greatest contributory factor however, is believed to be an inadequate rehabilitation program, which coincides with a premature return to sport(3). More proof is now highlighting the advantage of mostly using eccentric strengthening exercises at hamstring rehab performed at large loads at more musculotendon lengths(1,4).

Semitendinosus (ST), they’re involved with extension of the hip, flexion of the knee as well as providing multi-directional equilibrium of the tibia and pelvis. All 3 muscles cross the posterior component of the two hip and the knee joints which makes them biarticular. As a result, they need to continuously react to large mechanical forces created by upper limb, trunk and lower limb locomotion via concentric and eccentric contractions. These forces are greatly improved during athletic activity, which is a likely culprit due to their high injury frequency.

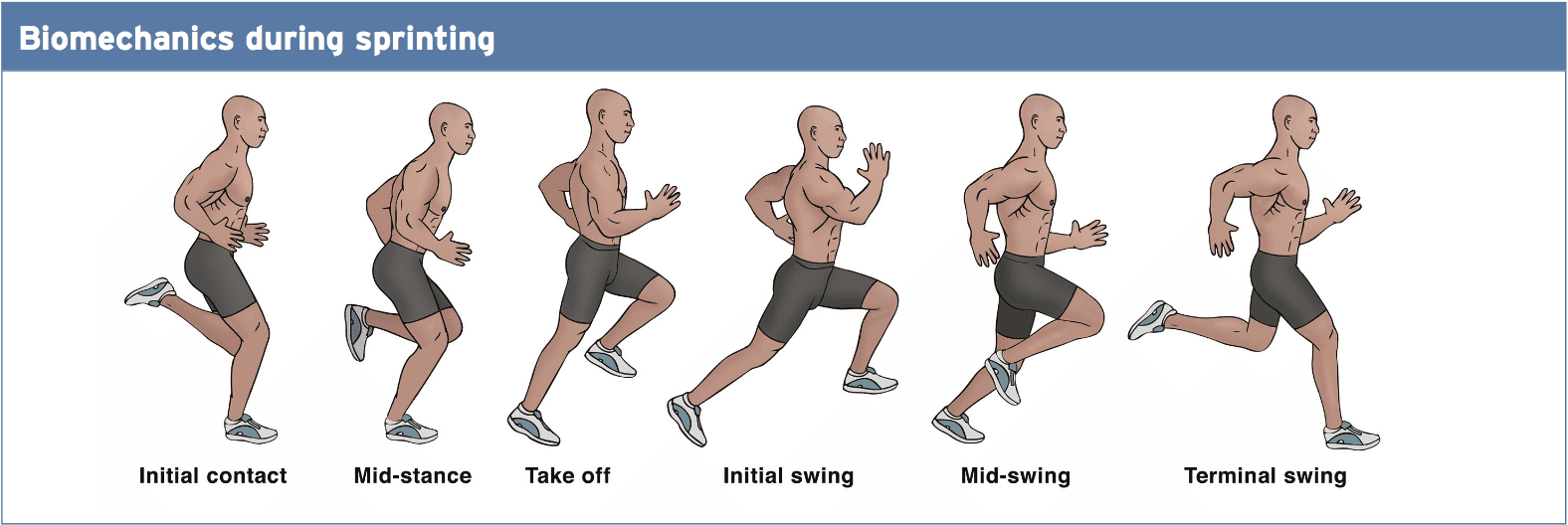

In a study at the University of Melbourne, biomechanical analysts quantified the biomechanical load (ie musculotendon strain, speed, force, power, and operate) experienced by the hamstrings across a full stride cycle during over-ground sprinting, as well as the biomechanical load across each person hamstring muscle(4).

Firstly, the hamstrings undergo a stretch-shortening cycle through sprinting, with the lengthening phase happening during the terminal swing and shortening phase commencing before foot attack, and ongoing throughout the stance. Secondly, the biomechanical load on the biarticular hamstring muscles has been found to be best during the terminal swing.

BFLH had the biggest peak musculotendon strain, ST demonstrated the best musculotendon lengthening velocity, and SM produced the greatest musculotendon force as well as absorbing and generating the maximum musculotendon power. This has ties in with other similar research, which divides peak musculotendon strain as a large contributor to eccentric muscle damage, ie hamstring injury, instead of peak muscle power(1); hence the recommendation of bizarre strengthening for acute hamstring rehabilitation.

Site Of Injury & Grading Classification

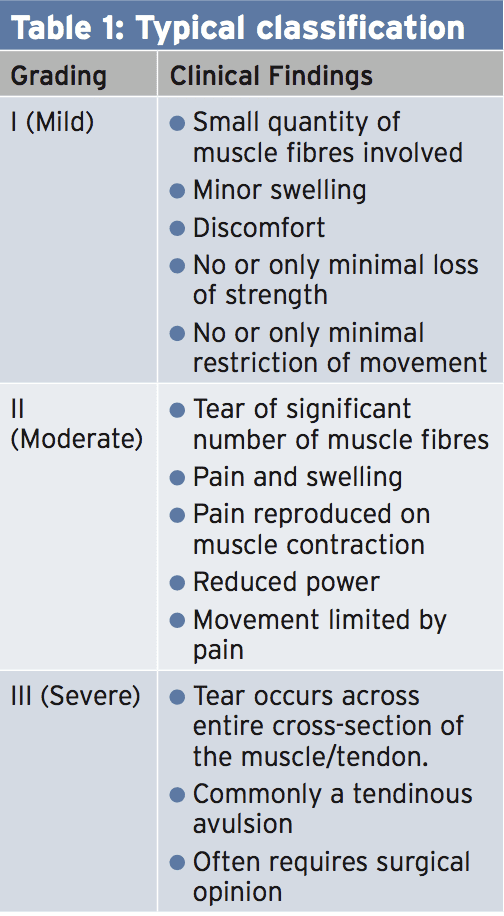

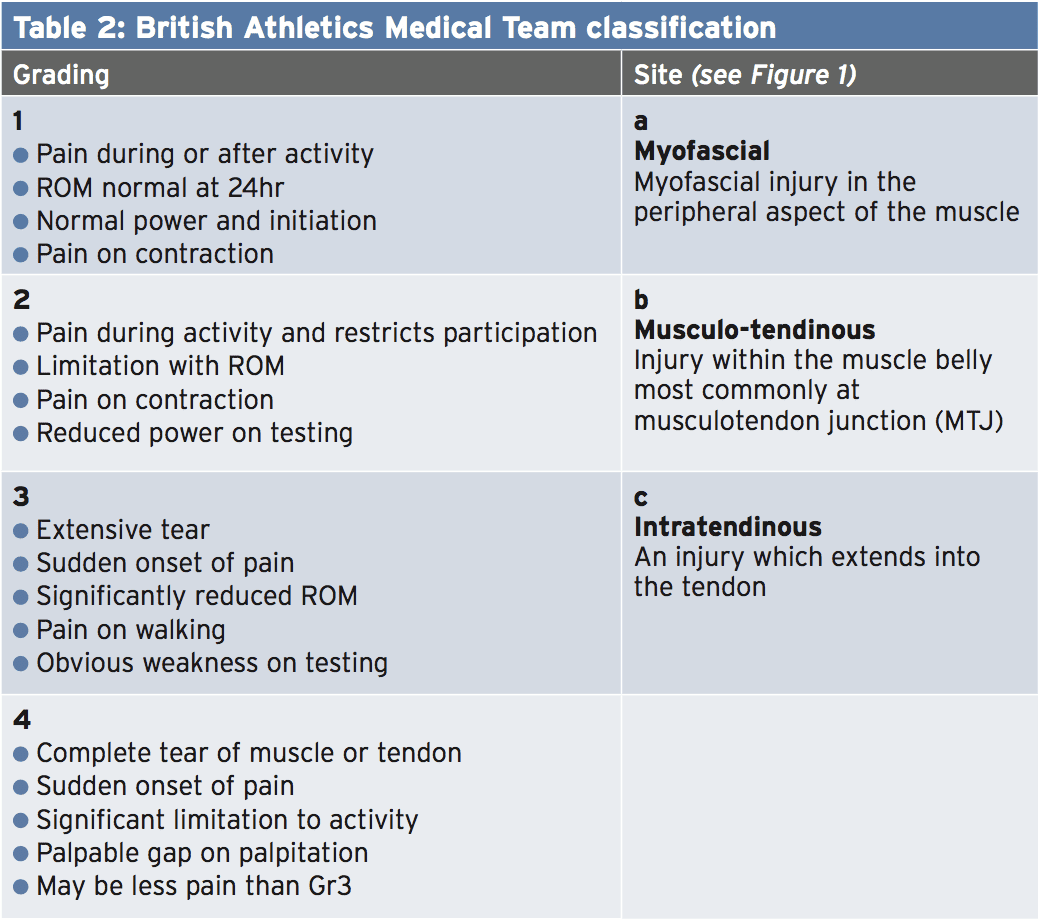

In a randomised controlled trial Professional Swedish footballers(1), the primary injury was situated in BFLH (69%). This contrasted with 21% of those players that sustained their principal harm within SM. It was common to maintain a secondary harm to ST in addition to BFLH (80\%) or SM (44%). A clear majority (94\%) of the most important injuries were discovered to be of the sprinting-type and were located in the BFLH, whereas, SM was the very common (76 percent) location because of the stretching- kind of harm. These findings were supported in another similar post(5).Typically (see Table 1), classification for Acute soft tissue injury, such as hamstrings, has depended on a grading system of I (moderate), II (mild), or III (severe) (2,6,7). This classification is useful concerning coherent descriptions between different medical staff members during clinical diagnosis and prognosis following severe injury.

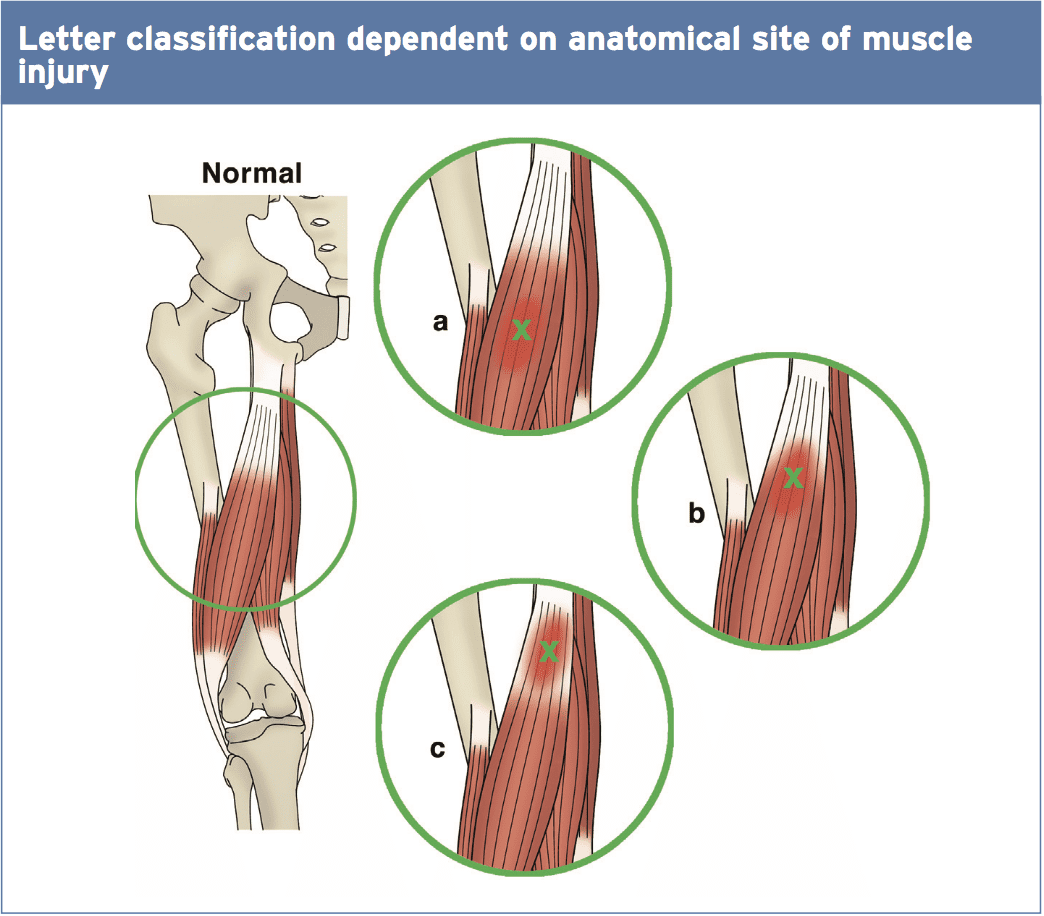

The British Athletics Medical Team Suggests a new injury classification system for improved diagnostic precision and prognostication based on MRI attributes (see Table 2 and figure below revealing ‘letter classification) (5).

Discovering true return-to-play Timescales following a severe hamstring injury has proven difficult. Injuries involving an intramuscular tendon or aponeurosis with adjoining muscle fibers (BF during high-speed running) typically require a shorter recovery period compared to those involving a proximal free limb or MTJ (SM during dancing or kicking)(2).)

Additionally, There Are connections between MRI Findings as well as the area of injury, and return-to-play. Likewise, the length of oedema indicates a similar effect on healing period — ie the longer the length, the more the retrieval(1). In addition, the place of peak pain on palpation following severe injury can also be linked with increased healing intervals(1).

Moreover, there have been efforts To explain the link between grading of acute hamstring injury and return-to-play. In a prospective cohort study on 207 professional footballers with severe hamstring injuries, 57 percent were grade I, 27 percent were grade II, and 3 percent were grade III. Grade I injuries returned to perform inside a mean of 17 days. Grade II was 22 days, and grade III was 73 days. Eighty four percent of those accidents affected the BF, 11\% SM, and 5\% ST, however there was no substantial difference in lay-off time for injuries to the 3 different muscles(5). This has been compared to 5-23 times with regular I-II injuries, and 28-51 times for grade I-III in other research respectively (1,8).

Rehabilitation – Eccentric Strengthening

Clinical trial on 75 footballers at Sweden, which noted that using eccentric strengthening versus the time to return-to-play was decreased by 23 days. This was irrespective of the sort of injury or the website of injury. The outcome measure was the amount of days to come back to full– team training and availability of match choice. This article will now research this study in greater depth.

Two rehab protocols were utilized, And initiation began five days after injury. All players had sustained a sprinting-type (top speed jogging/ speed) or stretching-type injury (high kicking, split places, slide handling). Exclusion criteria included previous hamstring injuries, injury to anterior thigh, continuing history of low back problems, and pregnancy.

Evaluation 5 days after the accident, to expose the severity and site of injury. A participant was judged to be fit to return to full-team training using the energetic ‘Askling H-test’ (see below). A positive test is when a participant experiences any insecurity or apprehension when performing the test. The test ought to be completed without full dorsiflexion of the ankle.

Seventy two percent of gamers sustained sprinting-type accidents, whilst 28 percent were stretching-type. Of these, 69\% continuing injury to BFLH, whereas 21\% was located from the SM. Injuries to ST were just continued as secondary injuries (48\% with BFLH, and 44\% with SM). Ninety four percent of sprinting-type injuries were located in the BFLH, while SM was the most common (76\%) location for the stretching-type injury.

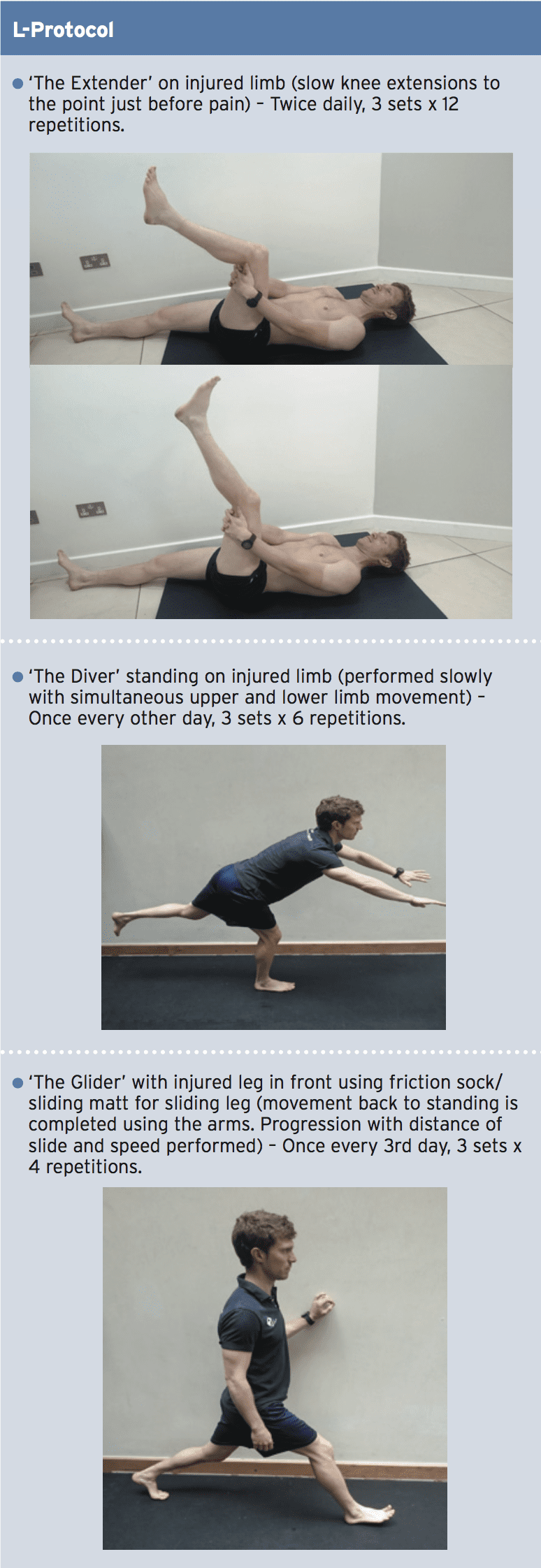

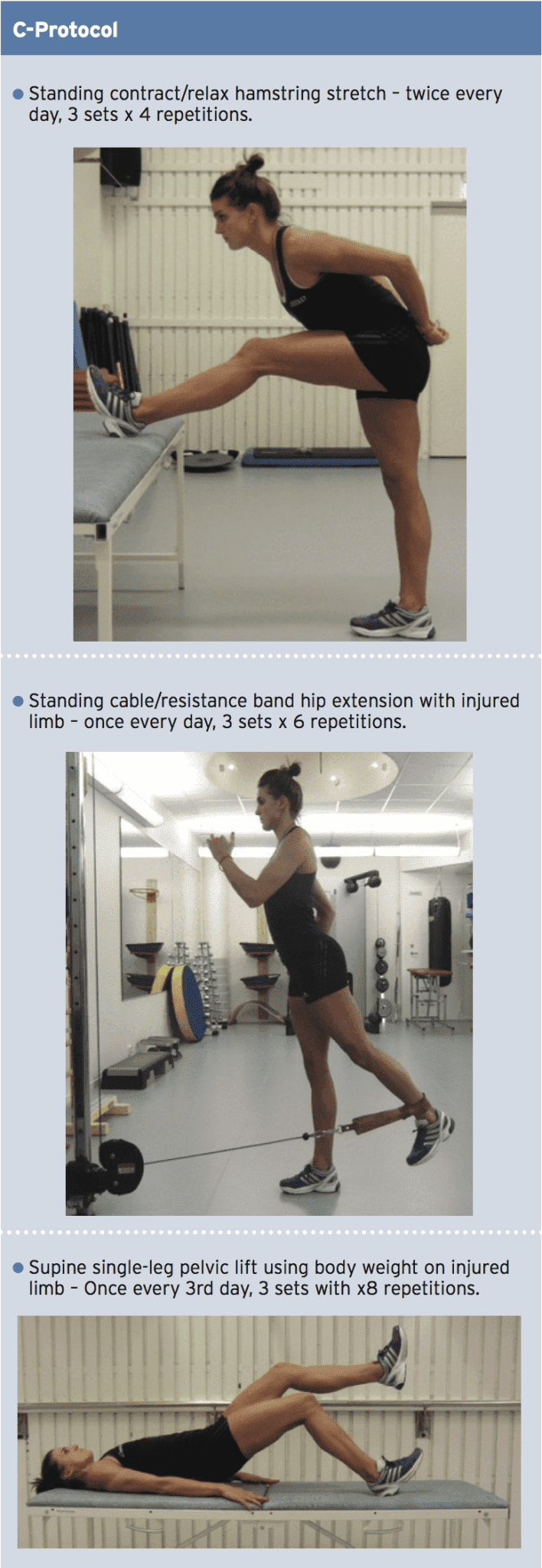

The two rehabilitation protocols utilized were labelled L-protocol and the C-protocol. One aimed at loading hamstrings through lengthening (L-protocol), and the other consisted of exercises with no focus on lengthening (C). Each consisted of three exercises that could be carried out anywhere and were not dependent of complex gear. They also geared toward controlling flexibility, trunk/pelvic equilibrium as well as specific strength training to the hamstrings. All were played in the sagittal plane with speed and load improved throughout.

Findings

The Opportunity to reunite was significantly shorter in the L-protocol compared with the C-protocol, averaging 28 times and 51 days respectively. Time to come back was also significantly shorter in the L-protocol than in the C-protocol for injuries of the two sprinting-type and stretching-type, as well as for injuries of different injury classification.Summary & Clinical Implications

Injuries can be classified from Grade I-III or maybe more specifically Grade 1-4 for severity and a-c depending on site of injury. This according to MRI findings. The closer the site of injury is into the proximal hamstring tendon, the longer the recurrence- to-play period. Employing eccentric strengthening exercises in rehabilitation programs will promote a quicker return- to-play.

To enable a thorough rehab procedure, clinicians will need to take into account the first hamstring weakness, Any lack of flexibility, previous hamstring accidents, age, exhaustion, and intensity and strength imbalances between hamstring (eccentric) and quadriceps (concentric) contraction.

References

1. Br J Sports Med 2013; 47: 953-959

2. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010; 40(2): 67-81

3. Sports Med 2004; 34: 681-695

4. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012; 44(4): 647-658

5. Br J Sports Med 2012; 46: 112-17

6. Musc Lig Tend J 2013; 3(4): 337-345

7. Brukner, P. in: Khan K. 2007 (3rd ed). Clinical Sports Medicine. Sydney. PA: McGraw-Hill Companies.

8. Sports Phy Ther 2011; 3(6): 528-533

9. J Biomech 2007; 40: 3555-3562