Recently, there has been an increasing interest in platelet treatment as a remedy for speeding injury recovery. But just how strong is the evidence for the use? Chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez looks at the latest research…

Of All of the injuries suffered by athletes engaging in game, those involving muscle tissue are one of the commonest injuries — accounting for up to 50% of reported accidents(1,2). Many muscle injuries result from excessive strain on muscle fatigue, during sprinting, jumping or other volatile contractions but they may also be the result of direct blows, or excessive eccentric contraction, even when the muscle develops tension while lengthening. In this kind of injury, the myotendinous junction of the superficial muscles involved is frequently affected –eg the rectus femoris, semitendinosus, and gastrocnemius muscles.

Regardless of the high frequency of muscle Injury in athletes, there’s still substantial debate among clinicians as to what constitutes the ‘best’ method of its remedy. Much of course will be dependent on the diagnosis and evaluation of muscle trauma — normally gained from a thorough clinical assessment. Imagining can provide additional guidance for your physiotherapist, although this often requires a referral between additional cost and time.

Despite these caveats above, few Clinicians would argue against the merits of several basic early therapy options to hasten the athlete’s return to sport practice. The most commonly used of these include rest, ice, compression and elevation (RICE) with a short period of immobilization through the first post- injury phase. In addition, the short-term utilization of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs), corticosteroid medications is frequently recommended(3-8).

More Than Medication

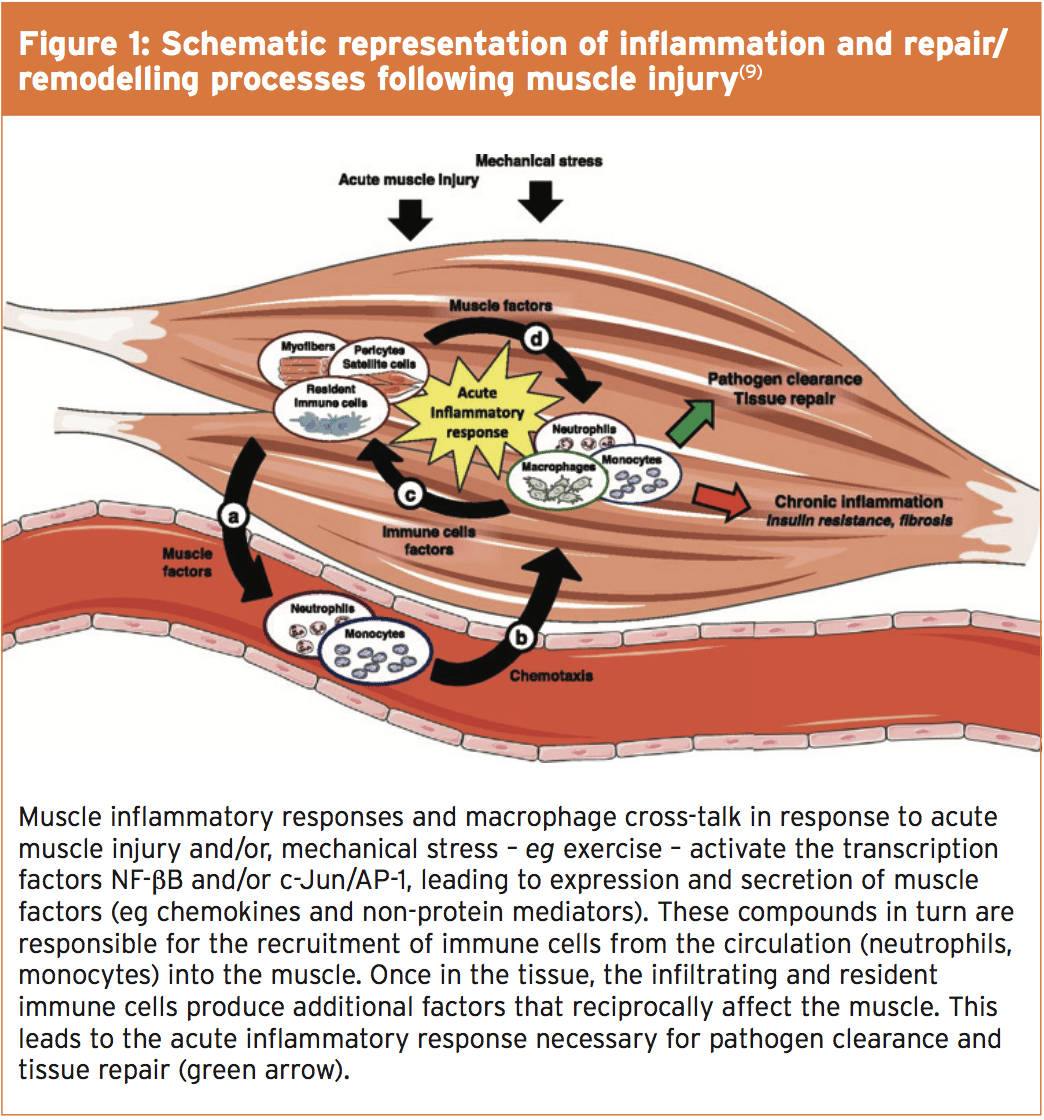

While medications such as NSAIDs and Corticosteroids have their place at the early stages of muscle injury therapy, there has been a growing interest in the use of autologous (cells and cells derived from ego) of biological products as an alternative or additional treatment for muscle injury. One such remedy is the use of blood platelets (blood cells whose purpose, along with the coagulation factors, would be to stop bleeding) as used in platelet therapy.Why platelets? When a muscle is Injured and damaged, it destroys a number of processes as part of the healing/repair process (see figure 1). Through this procedure, there are two Major stages:

- The early phase of destruction (inflammatory stage), where affected cells including muscles, blood vessels, connective tissues and intramuscular nerve undergo breakdown and death.

- The repair and remodelling stage, in Which undifferentiated satellite cells (in response to several growth factors) proliferate and differentiate into mature myoblasts in a bid to replace the muscle fibre tissue.

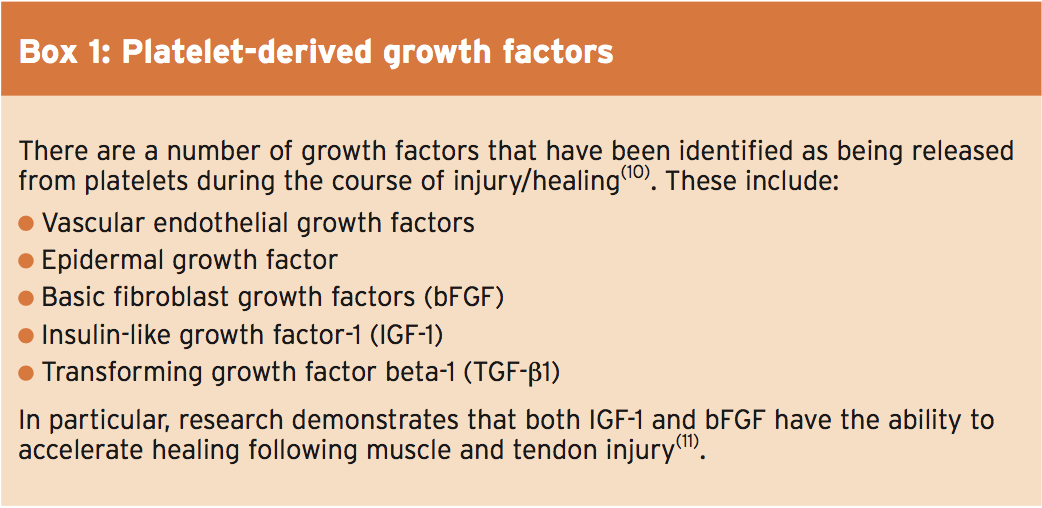

- In the inflammatory phase, the Inflammation happening after muscle trauma usually results in the accumulation of inflammatory cells, neutrophils and macrophages. In addition, blood platelet cells in the neighborhood of the wounded site become triggered. These activated platelets undergo ‘degranulation’ releasing various substances, including growth factors (see box 1), which are stored at the alpha (α) granules inside platelets(9). The accumulation of platelets in the vicinity of a muscle injury should consequently in theory provide more growth variables for the tissue, thereby aiding the repair and remodeling phase. Moreover, platelets contain other important substances requirement for tissue regeneration and repair, such as glue proteins, clotting factors and their inhibitors, proteases, cytokines and tissue glycoproteins.

Theory & Practice

Considering the discovery that platelets play a vital role in muscle tissue repair, it was not long before researchers wondered if platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections into the site of an injured muscle could accelerate healing period and so hasten the return to sport of an injured athlete. These platelet-rich therapies are produced by centrifuging a quantity of their patient’s own blood and extracting the energetic, platelet-rich, percent.A 2009 study using an animal model revealed that an autologous PRP injection significantly quickened tibialis anterior muscle recovery (from 21 days to 14 days(12). Indeed, prior to the, Sanchez et al introduced a similar finding at the 2005 World Congress on Regenerative Medicine. They noticed that athletes getting PRP injection under ultrasound guidance gained full recovery within half of the expected period(13).

However, in 2010, the International Olympic Committee concluded that ‘now there’s very limited scientific evidence of clinical efficacy and safety profile of PRP use in athletic injuries"(14). This position was underlined with a systematic review article published the next year, reporting ‘there’s been no randomized clinical trials of PRP impacts on muscle recovery"(15). Fast forward to 2015 and what does the research about the effectiveness or otherwise of PRP medications?

Latest Proof

At the last 2-3 years, a flurry of papers has been released on the use of PRP therapy for muscle trauma. A 2013 study on 30 professional athletes with severe local muscle injury seemed to give positive signs for PRP treatment(16). Prior to the intervention, most of the athletes failed and ultrasound and sonoelastography (a kind of ultrasound imaging that shows mechanical properties of tissue) examination. Patients were then randomly assigned to two groups:- Group A received targeted PRP Injection under ultrasound guidance and also additional conservative therapy

- Group B received conventional Conservative treatment only

Overall, the degree of pain relief has been greater in group A compared to group B Throughout the intervention. At the end of 28-day observation, 93 percent of pain Regression was announced by patients in Group A vs. 80 % of regression of pain in Group B. Also, at 7 and 14 days, significant Improvements in strength and range of Motion for PRP treatment team were observed. By the end of the study, Subjective global function scores improved Considerably in group A in comparison with Group B — as evidenced by the typical Return-to-sport occasions — 10 times in group A And 22 days in group B.

A 2014 systematic inspection meanwhile produced less encouraging findings about the value of PRP(17). The authors searched the literature for studies assessing the effects (benefits and harms) of platelet-rich therapies for treating musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries and where the primary results were functional status, pain and negative consequences. The analysis included data from 19 trials totaling 1088 participants who contrasted platelet-rich therapy with placebo, autologous whole blood, dry needling or no platelet-rich therapy. These trials coated eight clinical conditions:

Rotator cuff tears (arthroscopic fix) (six trials); shoulder impingement syndrome surgery (one trial); elbow epicondylitis (three trials); anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction (four trials), ACL reconstruction (donor graft site application) (2 trials), patellar tendinopathy (1 trial), Achilles tendinopathy (1 trial) and acute Achilles rupture surgical repair (one trial). The outcomes were as follows:

- Medium-term function statistics at six months from five trials showed no difference between PRP and management teams;.

- Long-term function data at one year pooled from 10 trials showed no distinction between PRP and the control state;

- Information gleaned from four trials that assessed PRP in 3 clinical conditions revealed a small Decrease in short term pain in favour of PRT but the clinical significance of this outcome was marginal;

- Seven trials reported an absence of adverse events after PRP therapy but four trials reported adverse events;

- Pooled data for long-term purpose from six trials through rotator cuff tear surgery revealed no statistically or clinically significant gap between PRP and management groups;

- The evidence for all primary outcomes was thought as being of very low quality not least because the Ways of preparing platelet-rich plasma varied and lacked standardisation and quantification of this plasma applied to the patient;

The results showed that patients at the PRP group attained full recovery significantly earlier than controls. The mean time to return to play was 42.5 times in the control group and 26.7 days in the PRP group. Significantly lower pain severity scores were observed in the PRP group throughout the study. But no significant difference in the pain disturbance score was found between the 2 groups. The authors concluded: ‘A single autologous PRP injection combined with a rehabilitation program is more successful in treating hamstring injuries than the usual rehab program alone’.

Conflicting Evidence

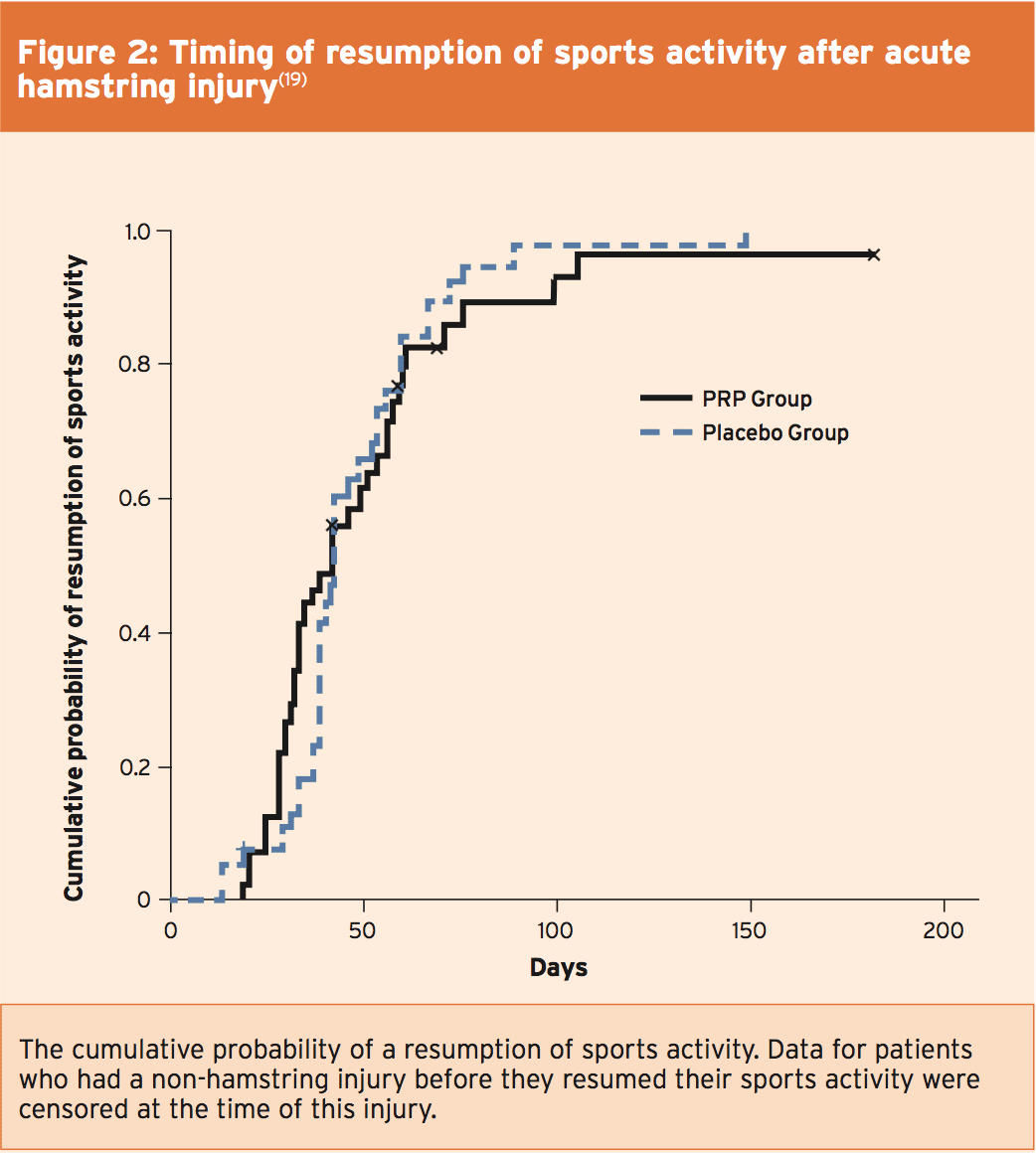

Later the exact same year however, a strict double-blind, placebo-controlled trial on the efficacy of PRP injections for acute hamstring injury brought very different conclusions(19). The researchers randomly assigned 80 competitive and recreational athletes with acute hamstring muscle injuries (as confirmed on magnetic resonance imaging) for intramuscular injections of PRP or isotonic saline as a placebo. Significantly, the patients, clinicians, and physiotherapists were oblivious of study-group assignments.Each patient received two 3-ml injections by means of a sterile ultrasound-guided procedure; the very first injection was administered within 5 days following the injury and has been followed 5 to 7 days after by the next injection. Patients in both research groups conducted an identical, everyday, progressively phased, criteria-based rehabilitation program, which was based on the best available evidence (detailed in the study). The speed of re-injury within two months following the resumption of sport action was assessed as a secondary outcome measure.

The result showed that the median time until the resumption of athletics activity was 42 days in the PRP group and 42 days too in the placebo group (see figure two). The re-injury rate was 16 percent at the PRP group and 14% at the placebo group Although statistical evaluation allowed for a small chance there was a clinically relevant between-group gap, the authors concluded in their analysis at least, intramuscular PRP injections provided no advantage over and over a placebo shot.

The rigorous design of this study and the comparatively large number of topics casts some serious doubts on the effectiveness of PRP treatment. As if to underline these misgivings, the researchers completed a 1-year follow-up study on exactly the exact same set of athletes (published just last month) to see if there were any longer-term advantages of PRP treatment that might not have been picked up at the initial study(20).) Specifically, they sought to set the re-injury speeds at one year following PRP, and some other secondary outcomes such as alterations in clinical and MRI parameters, abstract patient satisfaction as well as the magnifying outcome score. Analysis of this data revealed that just as at 2 months, one year after there were no substantial between-group differences in the 1-year re-injury speed, or some other secondary outcome measure.

Another very recent research into the effectiveness of PRP treatment was printed just a couple of months ago. Researchers discovered the data from 19 previous randomized controlled trials, which had compared PRP treatment in patients with severe or chronic musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries using placebo, autologous whole blood, dry needling, or no PRP(21). The authors concluded: ‘While several in -vitro studies have proven that platelet-derived growth factors can promote the regeneration of bone, cartilage, and joints, there’s currently insufficient evidence to support using platelet-rich therapy for treating musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries’. And as in the 2013 study emphasized previously(17), they also pointed out that there’s a need for the standardization of PRP preparation procedures. The last decision was that the only circumstance where PRP treatment might provide tangible benefits is when conservative treatment has failed and the next treatment option is an invasive surgical procedure.

Conclusions & Practical Advice For The Clinician

When a clinician has an athlete in their care, minimizing the healing time in order that return to game can take place whenever possible is an essential aim of any therapy. In concept, PRP therapy should accelerate healing and recovery and really, several earlier studies appeared to suggest that PRP is a worthwhile adjunct alongside conventional treatment. However, larger and more rigorously constructed studies have failed to discover good evidence for the benefits of PRP, either in the short or longer duration. One possible reason for the confusing picture is that the preparation of PRP is far from standardized, meaning that the active elements within an PRP treatment could vary tremendously from study to study. As clinicians, our purpose is to use evidence- based practice and on this basis, we must conclude that (as yet) there is simply inadequate evidence for using PRP treatment in treating sports-related muscle injuries.References

1. Am J Sports Med 2001, 29:300–303

2. Br J Sports Med 2001, 35:435–439

3. Curr Sports Med Rep 2009, 8:308–314

4. Sports Med 2004, 25:588–593

5. Clin J Sport Med 2003, 13:48–52

6. Br J Sports Med 2004, 38:372–380

7. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983, 65:1345–1347

8. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1996, 4:287–296

9. Thromb Haemost 2011, 105(Suppl 1):S13–S33

10. Br J Sports Med 2008, 42:314–320

11. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000, 82-B:131–137

12. Am J Sports Med 2009, 37:1135–1142

13. ‘Application of autologous growth factors on skeletal muscle healing’: Presented at 2nd World Congress on Regenerative Medicine, May 18–20, 2005

14. Br J Sports Med 2010, 44:1072–1081

15. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2011, 11(4):509–518

16. Med Ultrason. 2013 Jun;15(2):101-5

17. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Apr 29;4:CD010071

18. Am J Sports Med. 2014 Oct;42(10):2410-8

19. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:2546-2547

20. Br J Sports Med. 2015 May 4. pii: bjsports-2014-094250

21. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2015 Jan;32(1):99-10