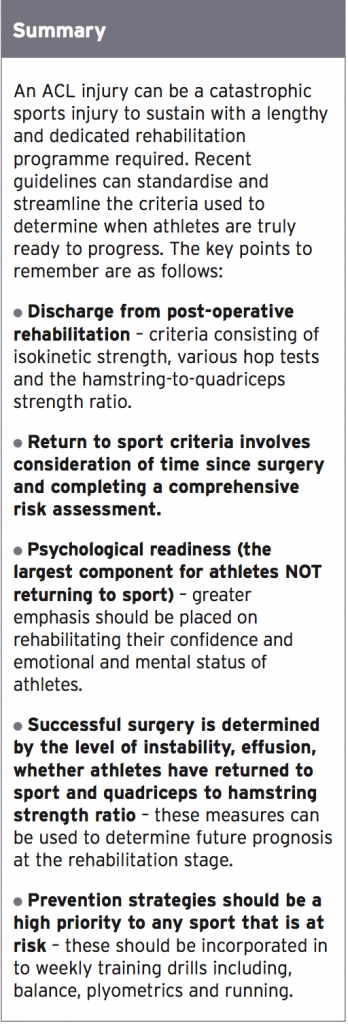

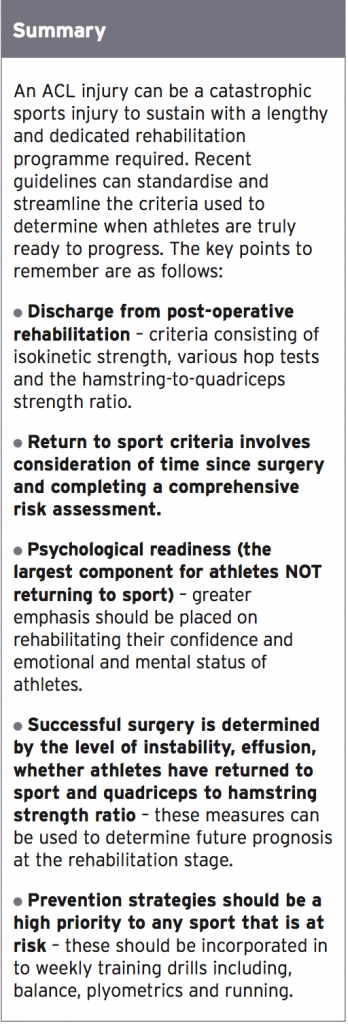

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries in athletes can have devastating consequences. Chiropractor, Dr. Alexander Jimenez examines the most recent guidelines for rehabilitation, return to sport, measures of success following ACL reconstruction surgery, as well as prevention strategies.

ACL injuries are one of the most common and debilitating sports injuries, usually occurring in sports involving pivoting, twisting, landing from a jump, or sudden deceleration. Football is one of the the most likely sports to produce an ACL injury because it encompasses all of these elements in a fast-paced environment.

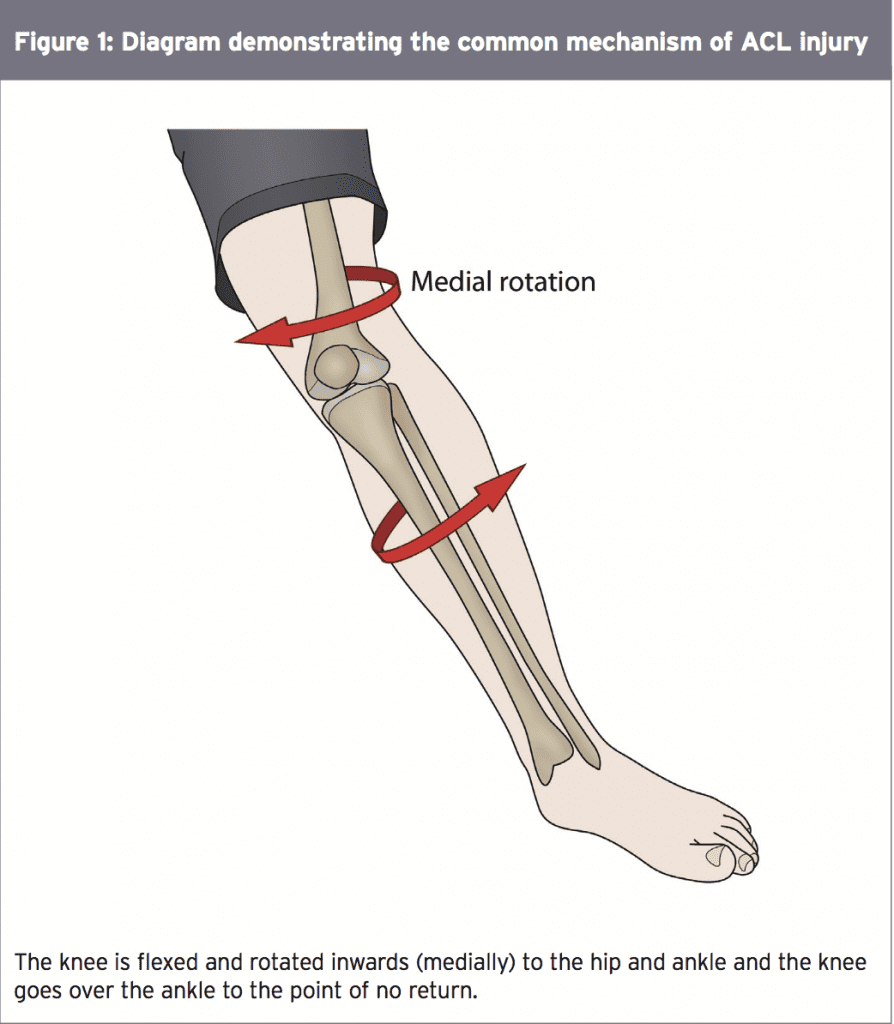

Approximately 60-80% of ACL tears occur in non-contact situations, where the knee is forced into a position of flexion and then rotation, bringing the knee inwards to the hip and foot, as per figure 1(1). Symptoms following an ACL tear include severe pain, swelling, inability to weight bear/limping, inability to fully bend or straighten the knee, instability and laxity.

Following an ACL injury, it is estimated that athletes should be able to return to sport within nine months of surgery. However this is widely variable and many will not achieve this level of rehabilitation within two years post-surgery(2). The level to which an athlete returns to sport is also questionable, with only around 50% returning to their pre-injury standards(3). Levels of an athlete’s pre-injury fitness, their gender or age do not apparently influence return to sport timings or success. This suggests that the most important factors are the quality of the rehabilitation measures and discharge to sport criteria.

Discharge Criteria

Return to sport requires stringent measures to ensure the athlete is ready for the demands of their sport. Too often an athlete’s desire to return and lack of extensive pre-training testing places them in a position of vulnerability when their strength, co-ordination, and neuromuscular control is not sufficient for the forces sustained in sports. In one recent study, those who did not meet six clinical criteria measures were four times more likely to sustain re-injury to their ACL surgery(4). The six identified criteria for discharge to sport were as follows:- Isokinetic strength testing

- Four hop tests consisting of a running T-test, single hop, triple hop, triple cross- over;

- Hamstring-to-quadriceps muscle strength ratio

Isokinetic strength testing refers to the strength of a muscle throughout its movement and is often tested at different ranges for a true representation. Research suggests there should be an 85% symmetry compared to the opposite leg before returning to activities(4). The hop tests measure dynamic strength, control, power and balance. A 90% symmetry is recommended for these tests(4).

The common perception is that quadriceps muscles are the main muscle group to rehabilitate following surgery – especially given their job of stabilising the knee and producing the powerful forces required to extend it.

However, the hamstring muscles are the graft source of choice usually, therefore creating immediate weakness. The hamstrings also work in union to the ACL to resist the forward movement of the tibia that the quadriceps produce; thus the hamstrings are key to preventing further ACL injury.

It is suggested that a higher hamstrings- to-quadriceps ratio is essential prior to sports. Research has indicated that for every 10% reduction in this ratio, there is a 10.6% increased risk of ACL graft rupture(4). Meeting these discharge criteria provides clear evidence for clinicians on the condition of the knee, and the effectiveness of the rehabilitation it has undergone. The time elapsed since surgery should also be considered.

The common perception is that quadriceps muscles are the main muscle group to rehabilitate following surgery – especially given their job of stabilising the knee and producing the powerful forces required to extend it.

However, the hamstring muscles are the graft source of choice usually, therefore creating immediate weakness. The hamstrings also work in union to the ACL to resist the forward movement of the tibia that the quadriceps produce; thus the hamstrings are key to preventing further ACL injury.

It is suggested that a higher hamstrings- to-quadriceps ratio is essential prior to sports. Research has indicated that for every 10% reduction in this ratio, there is a 10.6% increased risk of ACL graft rupture(4). Meeting these discharge criteria provides clear evidence for clinicians on the condition of the knee, and the effectiveness of the rehabilitation it has undergone. The time elapsed since surgery should also be considered.

Return To Sport Timing

The time elapsed since surgery alone does not reflect the condition of the knee; however there are still important implications relating to this post-surgery timeframe. The ligament reconstruction in ACL surgery requires time to heal and regain strength, as do the surrounding muscles which will have depleted in strength, stability and proprioception. This healing phase needs to occur despite extensive rehabilitation. Indeed, statistics show that around 70% of ruptures occur within the first 6 months post-surgery(4).A secondary concern is the significantly increased risk of osteoarthritis in those who also sustain a meniscal injury along with the ACL. Research suggests that 50% of these patients will require meniscus surgery within 5 years(5). Post-ACL surgery trauma could therefore accelerate this meniscal damage, increasing the prognosis of osteoarthritis from 0-13% to 21-48%, with a potentially significantly poorer outlook for future knee health(6). This is often because athletes return to sport too early and the surgery is not yet fully robust, coupled with the fact that the knee hasn’t regained effective neuromuscular function to cope with extra demands(4). Beyond 6 months however, there is a 50% reduction in rupture risk for every month return to play is delayed(7).

Despite progressing through and achieving the discharge criteria mentioned above, there should be further checks prior to returning to full competition. The recent World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy suggested a three-phase model that allows graded progression:

This phase should also see the introduction of open skills(8). Open skills allow for reactions, decision making, and the spontaneous elements of sport that cannot be practised within closed skills, which are routine, pre-prepared exercises. Open-skill training also allows optimal loading within the sports environment where fatigue will accumulate and the athlete can be assessed under more realistic conditions, but still within a controlled framework.

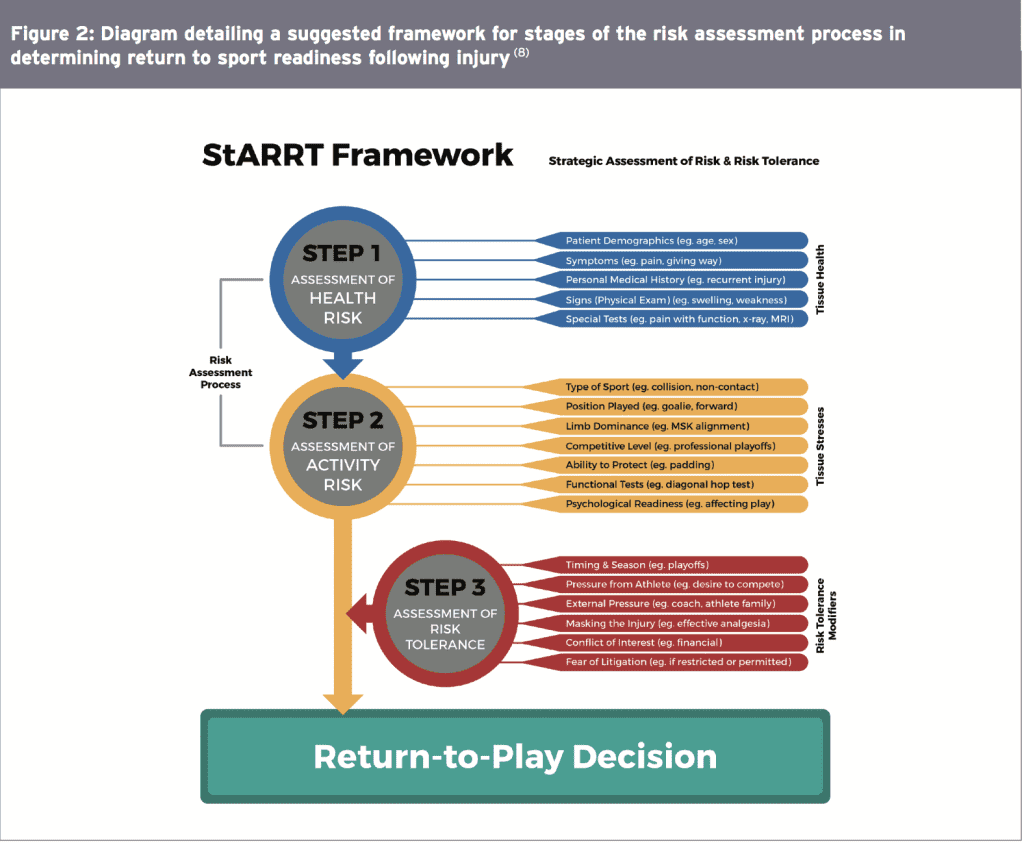

Figure 2 below details a thorough risk assessment that can be used to measure the athlete’s health, activity, and risk tolerance in returning to play. This model takes into account the multiple factors that should be considered including the condition of the tissues, the stress they will face, and the risks involved with sport after an injury.

Absence of instability – If the knee is symptomatic in giving way, this reveals failure of the surgical graft but also of the surrounding knee structures as it highlights an overall inability to stabilize the knee.

Absence of knee joint effusion/swelling – Effusion is routine post-surgery, occurring when the knee is unable to combat the forces placed upon it and inflammation presents within the joint. Following rehabilitation however, effusion should not be present at the one and two-year follow up marks that are used for measuring success.

Successful return to sport. The main purpose of undergoing ACL reconstruction surgery is to return to sport. It follows that if the athlete is achieving this, this is a successful outcome of the surgery. Their satisfaction and perception of the surgery should also be considered for a true measure of success.

Symmetry of quadriceps and hamstring muscle strength. The quadriceps are primarily important for long-term function. When a joint has been damaged the muscles can become impaired, giving reduced activation and therefore poor overall functional strength(12). Quadriceps weakness is also associated with post- surgical anterior knee pain and chronic pain issues. Hamstring strength usually resolves well within 1 year. However it was still reported as a factor; perhaps to allow equal balance of the limb with both major muscle groups performing equally.

Jumping and planting onto one leg can generate excessive force for the knee to withstand causing the surrounding muscles to fail and subsequently the ligament too. Cutting maneuvers occur where the athlete’s leg is in a position similar to that of Figure 2 above and then the athlete tries to change direction or fool their opponent by faking their intention. Regardless, the sudden direction change causes the knee to move further medially and the ACL (which is already on high tension) fails. Here the hamstring muscles are overpowered by the quadriceps and they pull the knee further into this vulnerable position.

- Return to participation – participating in rehabilitation and training but at a low level.

- Return to sport – returning to their specific sport but not at the normal skill level.

- Return to performance – participating in their specific sport and performing at or above their pre-injury level(8).

This phase should also see the introduction of open skills(8). Open skills allow for reactions, decision making, and the spontaneous elements of sport that cannot be practised within closed skills, which are routine, pre-prepared exercises. Open-skill training also allows optimal loading within the sports environment where fatigue will accumulate and the athlete can be assessed under more realistic conditions, but still within a controlled framework.

Figure 2 below details a thorough risk assessment that can be used to measure the athlete’s health, activity, and risk tolerance in returning to play. This model takes into account the multiple factors that should be considered including the condition of the tissues, the stress they will face, and the risks involved with sport after an injury.

Measures Of Success

The success of ACL surgery is an important consideration in planning the athlete’s future training and prospects. As well as the physical criteria, psychological factors, and risk assessments that can be completed, the surgical outcome should also be evaluated. A recent consensus evaluated the criteria assessing whether surgery has been a success(11). It concluded that the criteria of success should include:Absence of instability – If the knee is symptomatic in giving way, this reveals failure of the surgical graft but also of the surrounding knee structures as it highlights an overall inability to stabilize the knee.

Absence of knee joint effusion/swelling – Effusion is routine post-surgery, occurring when the knee is unable to combat the forces placed upon it and inflammation presents within the joint. Following rehabilitation however, effusion should not be present at the one and two-year follow up marks that are used for measuring success.

Successful return to sport. The main purpose of undergoing ACL reconstruction surgery is to return to sport. It follows that if the athlete is achieving this, this is a successful outcome of the surgery. Their satisfaction and perception of the surgery should also be considered for a true measure of success.

Symmetry of quadriceps and hamstring muscle strength. The quadriceps are primarily important for long-term function. When a joint has been damaged the muscles can become impaired, giving reduced activation and therefore poor overall functional strength(12). Quadriceps weakness is also associated with post- surgical anterior knee pain and chronic pain issues. Hamstring strength usually resolves well within 1 year. However it was still reported as a factor; perhaps to allow equal balance of the limb with both major muscle groups performing equally.

Prevention Strategies

Ultimately the smartest strategy is to prevent this injury before it can occur, but the unpredictability of sport means that the risk will always be there. Two common movements are known to precipitate ACL injuries; cutting maneuvers and jumping and landing on a single leg(1).Jumping and planting onto one leg can generate excessive force for the knee to withstand causing the surrounding muscles to fail and subsequently the ligament too. Cutting maneuvers occur where the athlete’s leg is in a position similar to that of Figure 2 above and then the athlete tries to change direction or fool their opponent by faking their intention. Regardless, the sudden direction change causes the knee to move further medially and the ACL (which is already on high tension) fails. Here the hamstring muscles are overpowered by the quadriceps and they pull the knee further into this vulnerable position.

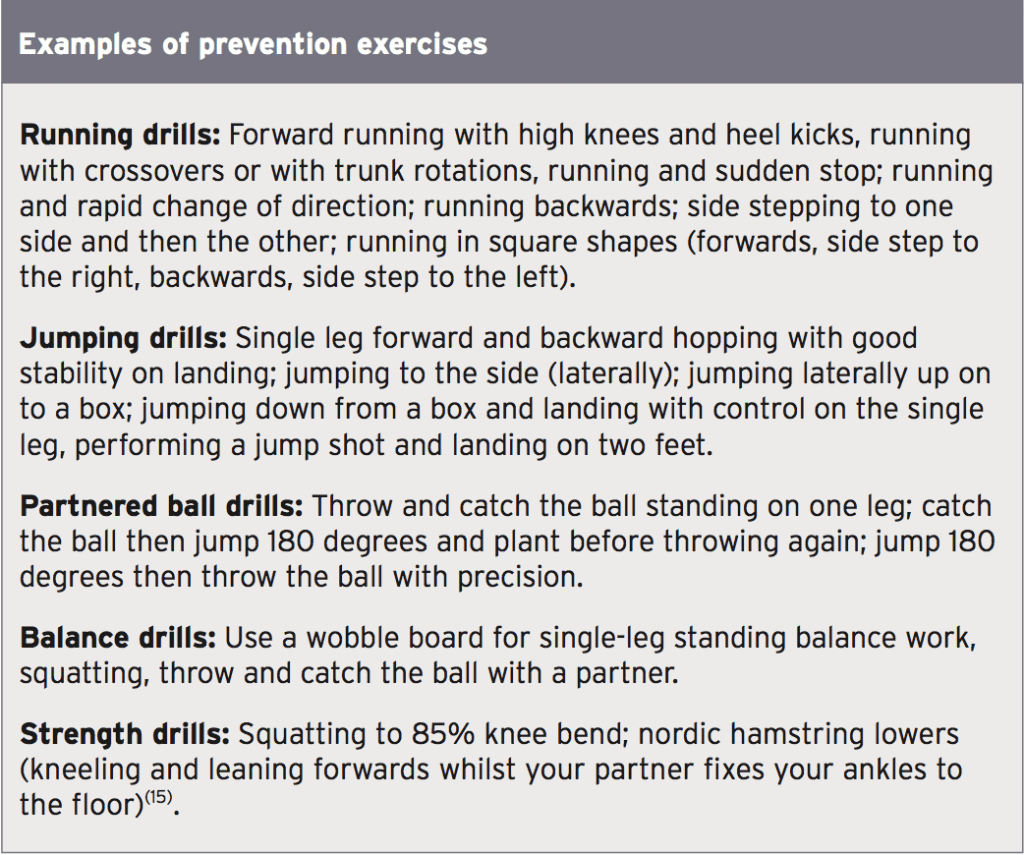

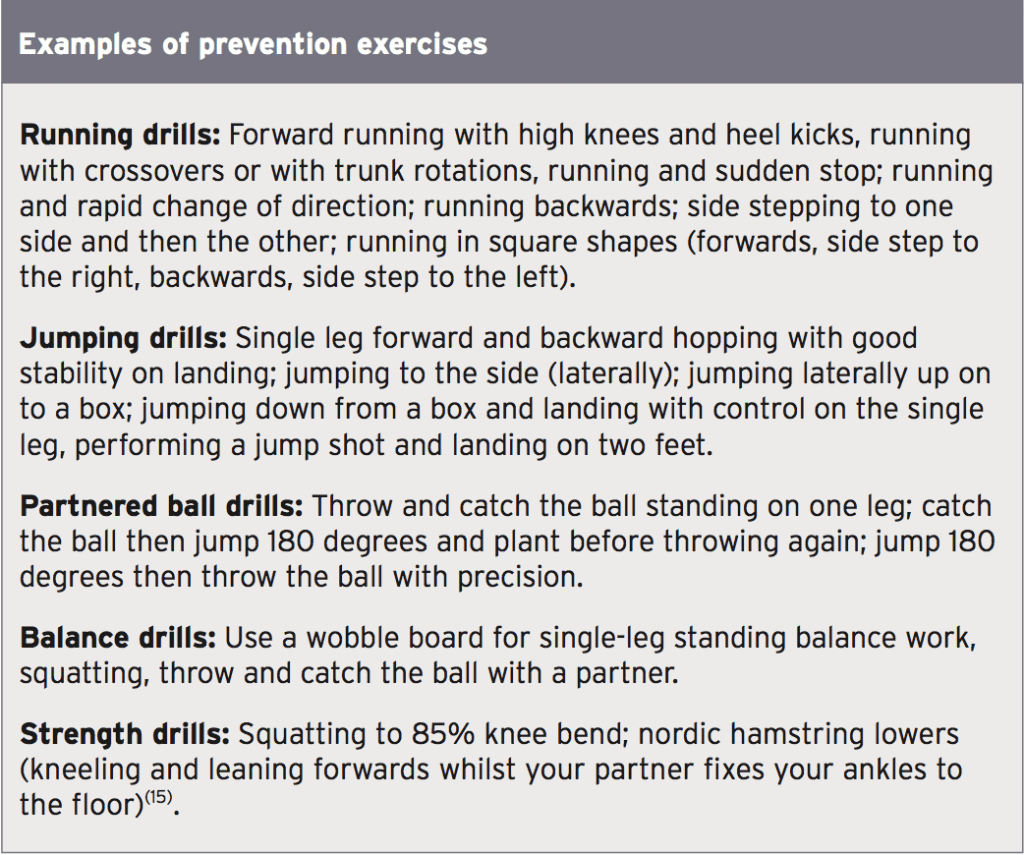

A 12-week program of participation three times per week of exercises aimed to reduce these mechanisms has been shown to increase hamstring muscle activation, which can counterbalance the quadriceps and provide protection against ACL injury(13). Prevention programs should be heavily focused on re-training balance, co-ordination, plyometrics, strength, and trunk stabilization (core work); the combined use of these exercise types has been shown to provide a protective effect against ACL injury(14). Furthermore, the use of verbal feedback giving technique cues during the exercise drills strengthened outcomes and improved anatomical corrections in the athletes(14).

Increasing the athlete’s awareness of these problematic movement patterns and practicing them in a controlled environment will strengthen the neuromuscular pattern, which helps the leg withstand higher, unpredictable loadings. Exercise drills should be performed until fatigue and with distraction to also mimic game environments, where accidents are more likely to occur.

References

1. Brukner P and Khan K (2009). Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd ed. Australia: McGraw-Hill Professional. 490-491

2. Am J Sports Med 2008. 36: 2028-2036

3. Br J Sports Med 2015. 49: 1295-1304

4. Br J sports Med 2016. 0: 1-7

5. BMJ 2013. 346-f232

6. Am J Sports Med 2009. 37: 1434-1443

7. Br J Sports Med 2016. Published online first: 9 May 2016 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016096031

8. Br J Sports Med 2015. 50: 853-864

9. Br J Sports Med 2016. 50: 471-475

10. Br J Sports Med 2014. 48: 1613-1619

11. Br J Sports Med 2015. 49: 335-342

12. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010. 40: 250-266

13. Br J Sports Med 2016. 50: 552-557

14. Br J Sports Med 2016. 0: 1-9

15. BMJ 2005. Feb 26; 33(7489):449, Epub

Increasing the athlete’s awareness of these problematic movement patterns and practicing them in a controlled environment will strengthen the neuromuscular pattern, which helps the leg withstand higher, unpredictable loadings. Exercise drills should be performed until fatigue and with distraction to also mimic game environments, where accidents are more likely to occur.

References

1. Brukner P and Khan K (2009). Clinical Sports Medicine. 3rd ed. Australia: McGraw-Hill Professional. 490-491

2. Am J Sports Med 2008. 36: 2028-2036

3. Br J Sports Med 2015. 49: 1295-1304

4. Br J sports Med 2016. 0: 1-7

5. BMJ 2013. 346-f232

6. Am J Sports Med 2009. 37: 1434-1443

7. Br J Sports Med 2016. Published online first: 9 May 2016 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016096031

8. Br J Sports Med 2015. 50: 853-864

9. Br J Sports Med 2016. 50: 471-475

10. Br J Sports Med 2014. 48: 1613-1619

11. Br J Sports Med 2015. 49: 335-342

12. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010. 40: 250-266

13. Br J Sports Med 2016. 50: 552-557

14. Br J Sports Med 2016. 0: 1-9

15. BMJ 2005. Feb 26; 33(7489):449, Epub