Menstrual dysfunction among female athletes is uncommon, but is associated with health consequences that are undesirable. Chiropractor Dr. Alexander Jimenez looks at new research, which points to a potential way ahead…

Introduction

In recent decades, there’s been much research from game and unsurprisingly so to the topic of disordered eating. Not only does this remain an intractable problem in men and (especially) female athletes, and across a wide range of engagement levels(1-6), but the low nutrient and calorie content that result from a lengthy period of sub-optimum nourishment can contribute to quite a few health problems. However, while recognized eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, anorexia athletica and bulimia nervosa are sure-fire paths to nutritional and health problems, it’s important to understand that for female athletes in least, sub-optimum nourishment and health can easily arise when there’s no eating disorder present.The Female Triad

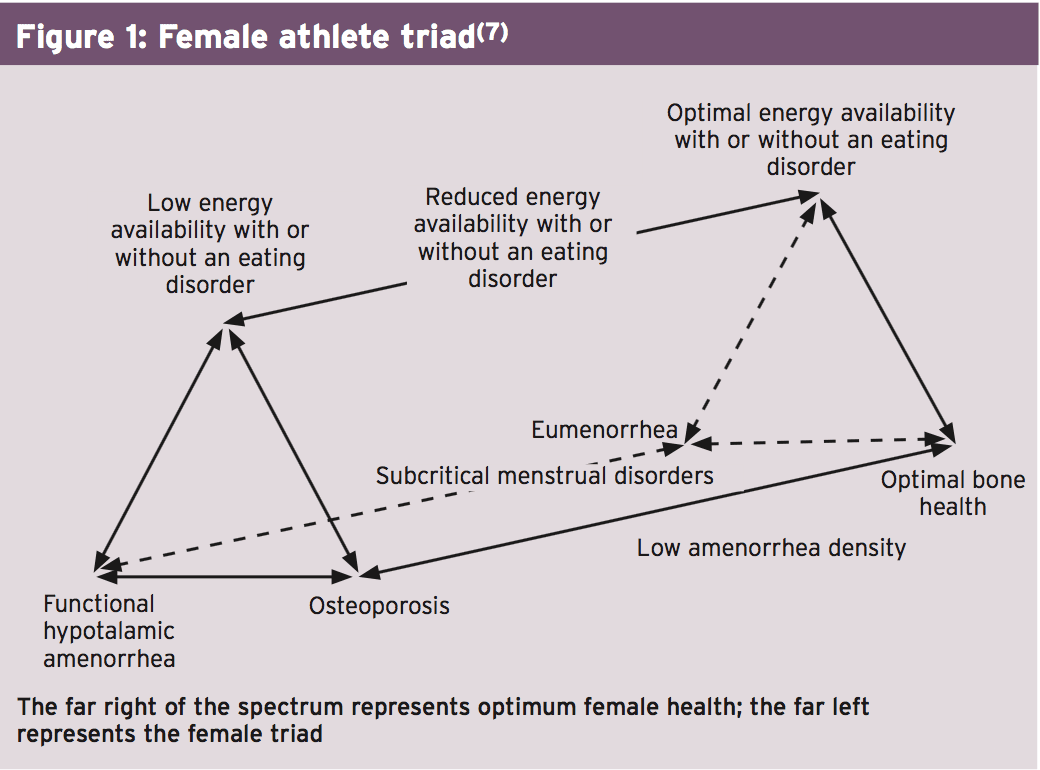

To understand this, we need to appreciate the interrelatedness of energy accessibility, menstrual function, and bone mineral density (BMD), which according to the American College of Sports Medicine defines the ‘female triad"(7). In very simple terms, the female triad describes how energy accessibility (dietary energy intake minus the energy necessary for exercise — ie the quantity of dietary energy staying for additional body functions after exercise training) may affect negatively on menstrual function and thus bone mineral density (see Figure 1).Energy Menstrual Dysfunction & Demand

In comparison to the overall female population, studies have found a greater incidence of abnormal menstrual role from the female athletic inhabitants(12-14). But while it’s true that there’s a greater prevalence of eating disorders among female athletes than the overall female population, we need to see that the high training loads and therefore energy requirements of some female athletes may easily lead to energy availability problems, even when eating patterns are regular.As stated above, ‘energy availability’ is defined as the amount of dietary energy available for all functions in your system once energy expenditure from exercise was taken into consideration. In young individuals that are wholesome, energy balance occurs at an energy accessibility of 45kcals a kilo of fatty mass per day. As an instance, assume a 50kg lady with 15% body fat has around 42.5kg of lean body mass. She would want 45kcals x 42.5 — ie approximately 1900kcals daily to achieve energy balance. By contrast, when energy availability falls to less than about 30kcals per kilo of free fatty mass daily, the reproductive function and bone formation are reduced to revive energy balance, resulting in an impairment of reproductive and skeletal health(15).

This deficit in energy availability of 15kcals a kilo of lean body mass equates to around 640kcals daily. This shortage can happen through simple calorie intake limitation — were our hypothetical female to go on a 1200kcal daily diet, her body would experience negative changes linked to the female triad and she would start to ‘move to the left’ about the triad spectrum (see Figure 1). Another route is that she does not increase her calorie count accordingly — and undertakes a training programme that involves expending 640 + kcals daily — by running nine mph easily achieved.

It’s easy to understand some some female athletes in sports like gymnastics, ballet dance, or figure skating, in which aesthetics and leanness are highlighted, are at risk of the female athletic triad.

Not only are they engaging in training, they might also develop poor nutrient behaviors such as food restriction, binging or purging etc in order to attain what they perceive as a perfect body form. Equally however, female endurance athletes undertaking large training volumes (eg triathletes) may often struggle to meet their energy needs despite having really healthy eating behaviours.

Health Implications Of The Female Athletic Triad

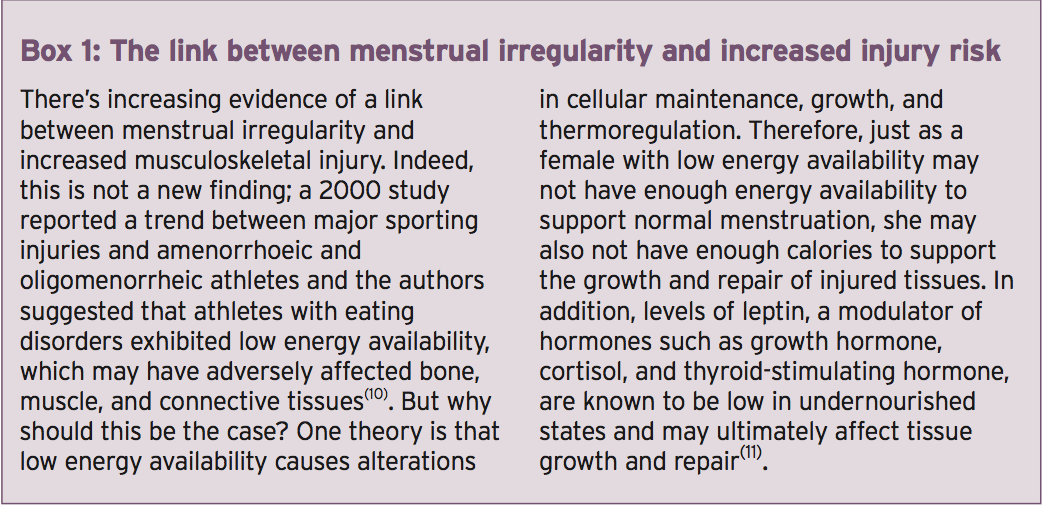

The health implications of this female athletic triad stem from the three key qualities of the illness — an energy (calorie) lack, menstrual dysfunction and reduced bone density.Energy deficiency — A moderate and short-term energy deficiency does not normally present problems, particularly if the diet is balanced and nutrient loaded. However, when energy shortages become bigger and occur over prolonged intervals, there are likely to be nutrient shortfalls (along with calories), which can lead to many different problems. These include decreased body mass, depleted glycogen stores, chronic fatigue deficiencies, anaemia, dehydration, erosion of tooth enamel disorders or electrolyte and acid-base imbalances. Psychological issues, such as anxiety, depression or diminished self-esteem, may also occur, particularly after prolonged periods of undernutrition(16).

Menstrual dysfunction — Menstrual cycle problems result in the reduction of the regular secretion of hypothalamic gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which consequently contributes to a diminished secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and thereby preventing ovarian stimulation, also inducing a drop in the levels of estrogens and progesterone. Early research indicated that menstrual dysfunction in female athletes has been due to too low body fat (below 17%). The theory was the sensitivity of the hypothalamus to steroids would be changed and this percentage of body fat the metabolic rate decreases. However, more recent research suggests that menstrual dysfunction isn’t caused by stress or a minimal proportion of body fat, but results from the disturbance of their GnRH ‘heartbeat’ as a result of low energy availability(17) — in other words having enough higher quality nourishment, low levels of body fat do not necessarily result in menstrual dysfunction.

Regardless of the mechanism, we all know that when menstrual dysfunction occurs, the resulting hormonal alterations can cause a number of complications; these comprise inadequate and damage repair of tissue, inhibition of thyroid and immune function, lost of their cardio- protective effects on lipids and vessel walls and changes in kidney function(18). Additionally, absence of stimulation of oestrogen receptors in blood vessels could result in impaired endothelium-dependent arterial vasodilation(19,20).

Bone health — since it encourages better bone mineralization, resulting in increased BMD and consequently higher bone power, Exercise is beneficial for bone health. But female athletes with menstrual dysfunction tend to have considerably lower BMDs than those with who don’t(21); the factors contributing to menstrual dysfunction may therefore put athletes at risk for compromised bone health and for the development of low BMD (osteopenia) and osteoporosis(22). A major factor for bone health as a result of menstrual disorder is diminished estrogen. Dysfunction causes a drop in estrogen levels, which is undesirable since estrogen helps preserve BMD. Low energy availability may impair bone formation through effects on other hormones like leptin and cortisol. Blend this with a likely shortfall in calcium and vitamin D intake (both of which are necessary for bone formation/maintenance) and it’s easy to understand why bone health can suffer.

The risk for athletes suffering from reduced BMD is stress fracture. Even though the prevalence of stress fracture can also be influence by other factors such as age, prior exercise, and alcohol intake, studies reveal that female athletes afflicted the female triad are especially at risk(23) The most frequent site of stress fractures in female athletes would be that the tibia, accounting for 25 percent to 63 percent of cases(24). Alarmingly, the effects of as a consequence of the female triad BMD seem to be somewhat persistent — to date no study has demonstrated that lost BMD could be recovered when athletes recover their status. Additionally, because peak bone mass is attained by the third decade old, the problem of diminished BMD is especially crucial for adolescent athletes(25).

Overcoming Menstrual Dysfunction In Female Athletes

Whether moderate or acute, disorder is widespread among female athletes. Given the health consequences, it is unsurprising that effort was aimed at reducing the prevalence of the condition. To date, much of the focus has centered about the discovery and treatment for eating disorders, which are common among female inhabitants. Trainers in training that is heavy may struggle to achieve a energy equilibrium despite excellent eating habits. This becomes an impossible undertaking when eating disorders are found.A number of the early eating disorder prevention programs have typically consisted of educational and psychological interventions; sadly however, research generally suggests that while this type of intervention is capable of increasing awareness about the problem, it’s less effective at actually changing eating behaviors(26,27). In more recent decades, eating disorder prevention programs have improved and programs with good empirical support would be the cognitive dissonance-based prevention (DBP) and the Healthy Weight Prevention Intervention (HWPI) applications(28, 29).

Regardless of the positive findings in the DBP and HWPI methods the issue is that neither has been properly tested on athletes — a population that may be resistant to making changes. Another consideration of course is that a number of athletes who suffer from dysfunction don’t have an eating disorder as such — instead they simply struggle to consume sufficient energy.

A Nutritional Approach

Since many female athletes with menstrual dysfunction don’t suffer from eating disorders, that in those who do, approaches to assist are guaranteed to operate, an obvious question is if there are? Back in the late 90s, researchers turned into a diet and exercise training intervention program designed to enhance energy balance and nutrient status in four amenorrhoeic athletes(30). Specifically, they wanted to check whether the intervention can reverse the athletes’ amenorrhoea . The 20-week program provided a sport nutrition supplement, which requested the athletes to take an excess day of rest per week, and boosted consumption by 360kcals daily. The results demonstrated that menses and ovulation has been revived in three of those four athletes — an encouraging finding.

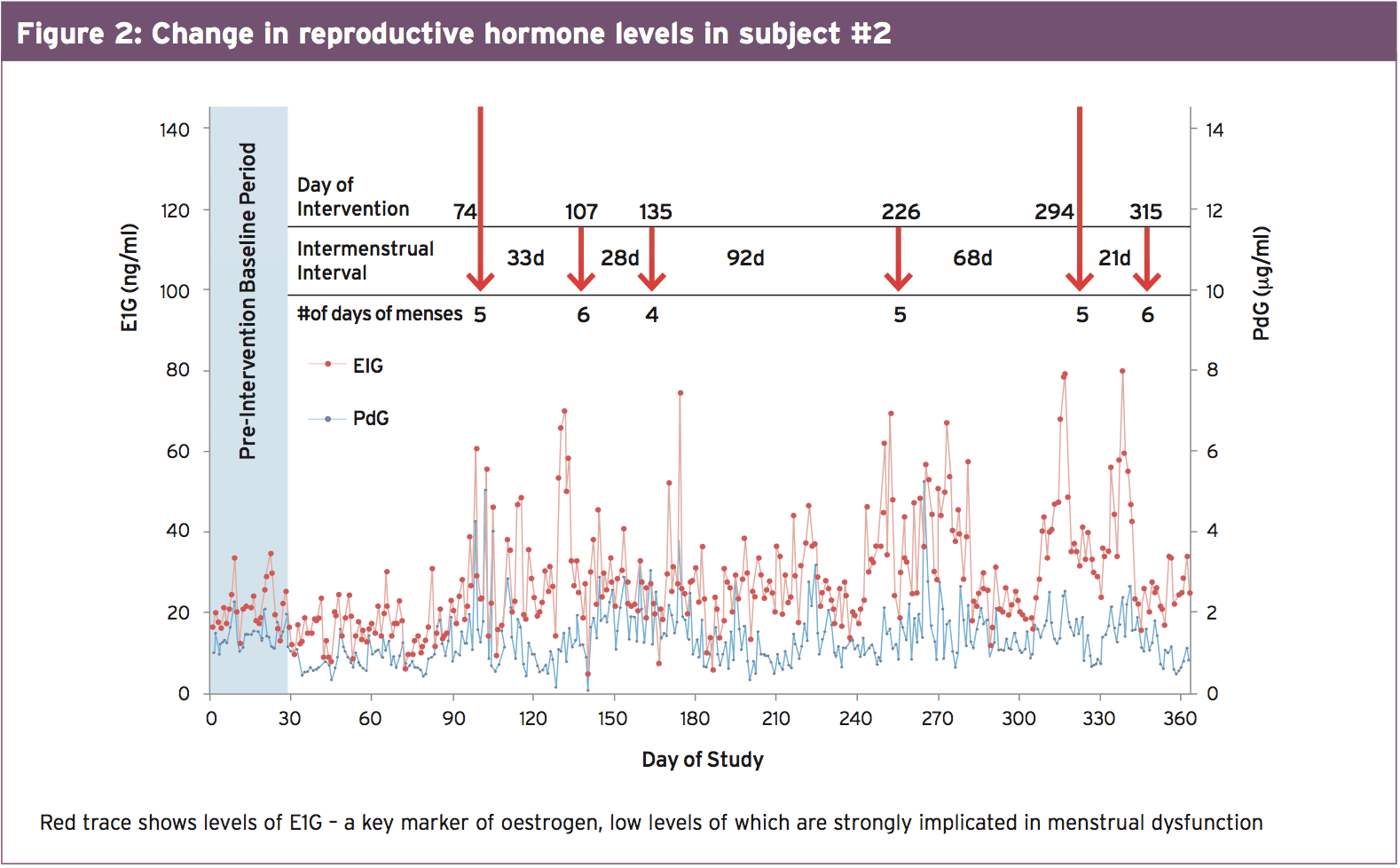

The problem is, of course, that lots of female athletes and/or their coaches are (quite naturally) loath to include rest times to their training programs. However, a 2013 case study on two female athletes makes for additional intriguing reading (31). Two athletes using amenorrhoea were chosen to investigate the effects of increased calorie intake on recovery of menstrual function and bone health. 1 participant (amenorrhoea for three months) was 19 years old and had a body mass index (BMI) of 20.4kg/m2 in baseline. She increased her calorie intake by 276kcals every day (13%), on average, during the intervention, and her entire body mass increased by 4.2kg (8 percent). The second participant (amenorrhoea for 11 months) was 24 years old and had a BMI of 19.7 kg/ m2. She improved her caloric intake by 1,881kcals every day (27%) and improved body mass by 2.8 kg (5 percent). Figure 2 shows how her reproductive hormones changed over the intervention period. Resumption of menses occurred 74 and 23 days to the intervention for those girls using short- duration and amenorrhoea along with the start of regular and ovulation cycles corresponded with changes. The following observation was that while no increases in BMD were detected from the 2 athletes, a marker of bone formation, P1NP, increased by around 50% in both areas.

Further Proof

The case study below suggests that just adding energy could be enough to help reunite amenorrhoeic athletes back into a regular cycle, with no need for extra rest. However, strong evidence can not be provided by a case study upon which to draw conclusions. But a recently published study by US scientists suggests that this method is indeed a legitimate one(32).The results showed that in relation to muscular strength/power bone health and hormone balance, there were no important changes. What was striking, however, was that each of the athletes resumed their menses, carrying on average 2.6 weeks to first menses (3.5 cycles). Another interesting observation was that athletes who had been longer or amenorrhoeic for 2 months took longer to restart menses than those amenorrhoeic for less than 8 months. As a side note, spinal area BMDs from the over- eight-month group were also significantly lower compared to under-eight-month athletes. There was A additional finding that POMS depression scores rose as a result of the intervention by 8 percent. The importance of these findings is that this study is the first to show that when athletes suffering from menstrual dysfunction consume an additional 360kcals every day for 2 months menses can be restored even though exercise training is continuing. As such, this approach could prove an extremely useful tool for helping female athletes who suffer from exercise-related menstrual dysfunction.

Summary & Conclusions

Menstrual dysfunction (using its associated implications for health) is surprisingly common in female athletes. A root cause is insufficient calorie intake. This may be as a result of an eating disorder, but a lot of athletes who have perfectly healthy eating habits may suffer with abnormal menses simply because of the high volumes of instruction (and so energy expended) they undertake. Disorder intervention/ prevention programs are of undoubted value where an eating disorder exists. However, restoring energy balance remains critical, where nutrient intervention appears to be extremely beneficial — to all athletes that struggle to meet their energy demands whatever the rationale, which is. Even more studies are still needed, the most recent research suggests that consuming a daily carbohydrate and protein nutritional supplement containing around 360kcals with approximately 2.5 parts of carbohydrate to one portion of protein could be a really effective intervention to normalize the menstrual cycle, together with all the health benefits that brings to the body.References

1. Clin J Sport Med. 2004 Jan;14(1):25-32

2. American Psychiatric Association: “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM-IV-TR), 4th Edition, June 2000

3. Int J Sports Med. 2007 Apr;28(4):340-5

4. Nutrition 2009 Jun;25(6):634-9

5. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003 May;35(5):711-9

6. Phys Ther Sport. 2011 Aug;12(3):108-16

7. Med Sci Sports Exerc; 2007;39(10):1867-1882

8. Bone. 2007;41(3):371-377

9. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006; 160(1 0): 1026-1 032.

10. Clin J Sport Med. 2000; 10(2): 110-116

11. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289(3):E373-E381

12. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2002;12(3):281- 293

13. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19(5):421-428

14. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(1):65-72

15. J Sport Sci 2007; 25: S67-S71

16. J Sport Sci 2007; 25: S67-S71

17. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2003; 31:144-8.26

18. Curr Sports Med Rep 2007; 6: 397-404(

19. PM R 2011; 3: 458-65

20. Clin J Sport Med 2011;21: 119-25

21. Bone 2009; 45: 104-9

22. Perform Enhanc Health 2012; 1: 10-27

23. Orthop Clin North Am 2006; 37: 575-83

24. Am J Sports Med 2006; 34: 108-15

25. Clin J Sport Med 2004; 14: 25-32

26. Psychological Bulletin. 2004; 130:206–227

27. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007; 3:207–231

28. Prevention Science. 2008; 9:114–128

29. J Consulting Clin Psychology. 2008; 76:329–34

30. Int. J. Sport Nutr. 1999, 9, 70–88

31. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2013, 10, 34

32. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3018-30