Shoulder pain is a common complication which affects many athletes who

participate in overhead sports, such as swimming, tennis and other throwing

sports. Overhead, physical activities primarily utilize upper extremity

movements that place tremendously high demands on the structures of the

shoulder as these often require increased muscular activation around the

scapula-thoracic joint and the glenohumeral joint. Researchers from previous

studies determined that abnormal biomechanics of the shoulder girdle and constant

or repeated overhead movements can lead to injuries in overhead throwing

athletes.

|

| Share Free Ebook |

Particularly, muscular imbalances around the complex structures of the

shoulder can develop abnormal activation patterns and inherent myofascial

restrictions, both which can cause a significant decrease in the athlete’s scapular

control and dyskinesis, leading to glenohumeral joint injuries resulting from

instability and impingement.

The serratus anterior, or SA, is one of the muscles of the scapula that functions

by providing a connection between the shoulder girdle and the trunk, however, it’s

often believed to be a dysfunctional muscle among shoulder pathologies. The

serratus anterior is a primarily offers movement to the scapula, contributing

to the maintenance of normal scapulo-humeral rhythm and motion. Due to its insertion

on the inferior and medial border of the scapula, it can produce upward

rotation and posterior tilting. Poor activation of the serratus anterior muscle

may result in limited scapular rotation and protraction, causing a relative

anterior-superior translation of the humeral head in relation to its glenoid

articulation, leading to sub-acromial impingement and rotator cuff tears.

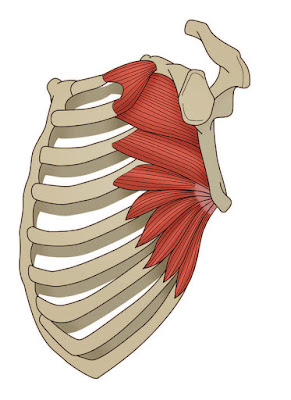

Anatomy of the Serratus Anterior

The serratus anterior is characterized as a flat sheet of muscle

beginning from the lateral surface of the first nine ribs. Then, it passes behind

and around the thoracic wall before inserting into the anterior surface of the

medial border of the scapula. The most important function of the serratus

anterior, or SA, is to protract and rotate the scapula, helping to maintain it

close yet away from the thoracic wall, allowing for the proper positioning of

the glenoid fossa to increase the efficiency of upper extremity motion to its

maximum state. The anatomy of the SA can be broken down into three anatomical

components as follows:

First, the superior component of the

serratus anterior begins from the first and second ribs, which then inserts

into the superior medial angle of the scapula. This fundamental section serves

as the anchor that allows the scapula to rotate when the arms are lifted

overhead. These fibres run parallel to the 1st and 2nd rib;

Second, the middle component of the SA begins

from the second, third and fourth ribs, which then introduces into the medial

border of the scapula anteriorly, in between the scapula and ribs. This basic

part is essential for the protraction muscle of the scapula;

And last but not least, the inferior

component of the serratus anterior originates among the fifth to ninth ribs and

inserts on the inferior angle of the scapula. The fibres within this region are

designed to form an arrangement similar to a quarter fan, which then implants

onto the inferior border of the scapula. This third and last portion serves to both

protract the scapula and rotate its inferior angle upwards and laterally. It’s

been previously proposed that the lower section of the serratus anterior

carries out the stability of the inferior border of the scapula, also

functioning with the lower trapezius to create a simultaneous force to upwardly

rotate the scapula during overhead movements for specific sports and physical activities.

Essentially, the serratus anterior primarily operates to upwardly rotate

the scapula during shoulder abduction, principally from 30-degree shoulder

abductions onwards, it also stabilizes and protracts the scapula during

shoulder flexion movements, rotates the inferior angle, or the posterior tilt,

of the scapula, balances the scapula against the thorax during forward pushing

movements to prevent the abnormal function of the tissues, and it also functions

to firmly hold the medial border of the scapula against the thorax to ensure

that it can change the thorax posteriorly during a push up with the hands fixed.

For an athlete, certain movements in particular with their specific

sport or physical activity can require a high level of function from the SA in

order to achieve either full scapular protraction and/or upward rotation.

Examples of athletic performances requiring the function of the serratus

anterior include: throwing a punch in boxing to achieve maximum reach of the

arm. Because of this, the SA is frequently referred to as the boxer’s muscle.

Among boxers, the serratus anterior is crucial for the scapula to be able to

brace on impact with the punch, allowing for maximum transfer of force from the

lower limbs into the torso for it to transmit into the upper limb and punch. If

the scapula were to collapse from the impact of a punch, the boxer would then

lose power in their punch. In swimmers, a full upward rotation is necessary for

the athlete to achieve a maximum reach in the water upon hand entry in freestyle

and butterfly swimming. An overhead athlete, such as a tennis player, utilizes

a full upward rotation when serving. Among the sweep style rower, the athlete

needs full protraction on the longer region to achieve the required reach

during the catch phase of the rowing stroke. And in baseball, for example, the

pitcher requires high levels of protraction to follow through with a pitch,

similarly, in the throwing events in athletics.

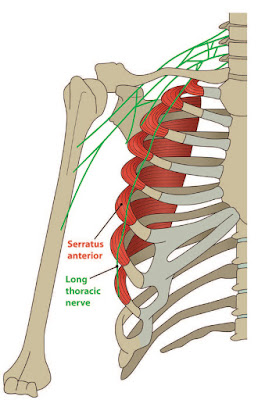

The long thoracic nerve can be found within the serratus anterior, which

originates from the fifth, sixth and seventh cervical nerves. These nerves then

pass through the scalenus medius muscle before they another cervical branch of

nerves which travels through to the scalenus medius as well. The long thoracic

nerve then passes through the brachial plexus and the clavicle to pass over the

first rib. In this section, the nerve enters a fascial sheath and continues

traveling along the lateral feature of the thoracic wall through the serratus

anterior muscle.

SA Dysfunction & Scapula Dyskinesis

The proper

positioning of the humerus within the glenoid cavity, best referred to as the

scapulo-humeral rhythm, is essential towards the proper function of the

glenohumeral joint during overhead movements. Any alterations in the normal

motion of the scapula may cause an inappropriate positioning of the glenoid

relative to the humeral head, causing injury to the SA due to impingement and

instability and resulting in shoulder pain and other symptoms. The right use of

muscle activation and the adequate levels of muscle recruitment are also needed

to position the scapula in the proper position. Small changes in the activation

of the muscles around the scapula can affect its alignment as well as the

forces involved in upper limb movement. The serratus anterior is one of the

primary muscles responsible for maintaining normal rhythm and shoulder mobility.

Several healthcare professionals have helped reduce the pain caused by

impingement by actively repositioning the injured individual’s scapula into a

proper posture by reducing its anterior tilt, increasing the strength of the

shoulder during overhead activities. The SA is a muscle that actively functions

to position the scapula into posterior tilt during specific sports involving

overhead motions.

If there is a lack of strength or endurance in the SA, the muscle also

allows the scapula to rest while in a downwardly rotated and anterior tilted

position, causing the inferior border of the structure to become more

distinguishable. Moreover, an imbalance between the serratus anterior and the

other muscles surrounding it, such as the pectoralis minor, may result in what

is known as a winging scapula. Scapular winging may speed up or contribute to

the development of constant symptoms among athletes with orthopedic shoulder

pain and injuries.

Scapular winging can be identified by observing the position of the

scapula during a push up exercise. Often, if the winging is due to a muscle imbalance

and the primary scapula stabilizer is the pectoralis minor, this will generally

correct itself if the individual is asked to protract their scapula. If the

wing disappears then the cause is most likely muscle imbalance and if it remains,

then it may be a pathological inhibition of the SA. Other instances of scapular

winging can also occur due to pathological damage or injury to the long

thoracic nerve found within the serratus anterior muscle.

The Significance of the SA

The necessary conditioning of the serratus anterior muscle among an

athlete has been previously evaluated in studies regarding sports such as

swimming, throwing, and tennis. A fatigued SA muscle can ultimately reduce the

rotation and protraction of the scapula, which allows the humeral head to change,

most commonly leading to secondary impingement and rotator cuff tears. Further

studies on the role the serratus anterior plays in shoulder pathologies has also

been analyzed by many other researchers. Some of the most important and

noteworthy key points have been summarized and recorded by researchers as

follows:

While the researchers conducting these studies evaluated the trapezius

and serratus anterior among individuals suffering from shoulder pain and

injuries, it was compared with those without damage or injury to the shoulder,

and it determined that the upper trapezius can demonstrate increased activity

during the raising and lowering of the arm. The results show how the SA can

decrease activation at some elevation angles.

Then, the study also evaluated the muscle activation patterns of

swimmers with shoulder pain, comparing it to those without, and found that the

middle and lower serratus anterior decreased activity in all phases of swimming

motion. This can be a possible cause for shoulder pain or other complications

where the swimmer uses compensatory muscle activation patterns.

Scapular Winging & Winging Correction #1

Similarly, other researchers have identified an inactivity or activation

delay in the SA surrounding the painful shoulders of swimmers while they raise

their arms in the scapular plane. It’s also been previously hypothesized that

individuals with decreased serratus anterior activations have a closer

association with an increased chance of developing shoulder pain and/or

instability while the increase in lower trapezius activity may function to

compensate for decreased serratus anterior activation. Other studies relating

to various types of shoulder dysfunction, found decreased serratus anterior

activity and increased upper trapezius activity, without a change in lower

trapezius activity among subjects with shoulder injuries when compared to

subjects without shoulder complications.

Scapular Winging & Winging Correction #2

The specific position of the scapula has also been associated with the

rotator cuff’s ability to function effectively. An excessive anterior tilt of

the scapula, an internal rotation or an excessive elevations of the acromion

are elements which can decrease rotator cuff activations, ultimately causing insufficient

handling of tension along the tendons. These circumstances can debilitate the length-to-tension

ratio of these muscles, leading to the loss of stabilization and an increasing

risk of muscular disruption or degeneration within the serratus anterior or

other tissues surrounding the shoulder. It’s been demonstrated that the

function of the rotator cuff can improve the functioning of the scapula

muscles, primarily the SA and lower trapezius.

Exercises for SA

A considerable amount of research has been conducted to find the best

rehabilitation exercises for serratus anterior muscle damage or injuries. The majority

of these studies analyzed the specific movements performed during push-ups,

push-up-plus exercises and cable/dumbbell punch type movements. These exercises

basically emulate the function of the SA in its protraction role. The studies

noted several important findings.

First, resistance was applied with eight scapulo-humeral exercises

performed below shoulder height that target the SA muscle in order to design a

progressive rehabilitation plan of serratus anterior muscle exercises along

with training. According to these researchers, the best exercises are push-ups,

dynamic hugs, scaptions and SA punch exercises.

The studies are found interesting effects of

vibration on the activation of the serratus anterior muscles and found that the

push-up plus exercise performed increased SA muscle activity. Additionally, the

effects of an unstable surface on the upper and lower parts of the SA while

performing variations of the push-up exercises were evaluated and the results

indicated that different parts of the serratus anterior have distinct functions

towards the stabilization process of the muscle. The authors of the study

concluded that the main role of the lower SA is the fixation of the scapula

onto the thoracic wall. Furthermore, they recommended athletes should perform

the push-up plus on an unstable surface as a more effective strategy for the

specific mobilization of this component of the SA.

The following exercises are examples of clinically used serratus

anterior activation exercises which have been proven to increase the levels of

function.

Shoulder Strengthening

The above

shoulder strengthening stretches and exercises can also help strengthen the

muscles surrounding the shoulder which can help prevent injuries and other

complications common among many athletes. Performing the following stretches

and exercises can be beneficial towards the rehabilitation of damage or injury

to the serratus anterior muscles. Before participating in any form of physical

activity after suffering an injury, make sure to consult a healthcare professional

on the recommended workout routines for each individual.

Wall Slider

To perform

this exercise, using a foam roller or pool noodle on the wall, place the wrists

against the roller with the forearm in a neutral starting position. Then,

protract the scapula so the space between the shoulder blades fills with an

increase in thoracic kyphosis. Slowly flex the shoulder so the roller moves up

the wall, making sure to supinate the forearms, to reach as high as possible

into shoulder flexion. The finish point is when the little fingers touch and

the forearm is in maximum supination. Slowly descend and return to the starting

point. Perform three sets of ten repetitions.

Swiss Ball Rotations

The athlete

can perform this exercise by holding a Swiss ball between the arms with the

ball gently resting on the chest while the forearms are in a neutral position. Then,

slowly rotate the trunk to the left. The arms will glide around the Swiss ball.

As the arm protracts, slowly rotate the palm upwards to encourage supination of

the forearm and external rotation of the shoulder. Return to the start

positions and start again.

TrX Serratus Rollout

The

individual participating in the exercise should first place the forearms

through the loops of a TrX or other suspension device, placing the straps at

wrist level or just below the elbows to differentiate the exercise load. The

start position is similar to that of the wall slider above followed by slowly

flexing the shoulder to elevate the arms above the head while slowly externally

rotating the shoulder by supinating the forearms. The finish position is when

maximum flexion/elevation is achieved and the little fingers touch. Return to

the start position and perform three sets of fifteen repetitions.

TrX Push Up Plus

The athlete

participating in the exercise should first position the handles on a TrX about

two to three feet off the ground. Holding the handles in a push-up position,

slowly perform a push up and slowly screw the hands into supination and

shoulder external rotation. At the top of the exercise movement, protract the

scapula and fill in the space between the shoulder blades with a slight

thoracic kyphosis. Return to the bottom position and perform three sets of ten

repetitions.

In conclusion, the serratus anterior, or SA, is a muscle that plays an essential role

in the movement and control of the scapula during pushing movements and

overhead activities. Specifically, it is a protractor, upward rotator,

posterior tilt muscle of the scapula and additionally, it fixes the scapula

against the rib cage during movement. Ultimately, It is a crucial muscle for

the overhead athlete as dysfunction in this muscle can lead to shoulder

injuries such as impingement, rotator cuff tears and performance issues during

overhead tasks.

By Dr. Alex Jimenez