Injury chiropractic specialist, Dr. Alexander Jimenez Looks in the best ways to monitor and reduce injury within this high pressure, high-stakes world...

Introduction

Football, otherwise known as soccer or association football, is the most popular team game played across the world. The four- yearly FIFA World Cup is the 2nd most watched sporting event behind the Olympics. It is thought that the origin of association football or football (and all the offshoot football sports like NFL, Rugby, AFL etc) started from the Greater Public Schools of England sometime in the 15th and 16th century and evolved to organized sports as they were taken globally around the world through the British Empire.As a consequence of multimillion dollar TV rights deals, the ownership of clubs by wealthy billionaire football fanatics and the unparalleled popularity of soccer, players are exposed to rapidly increasing amounts of professionalism. The ordinary team participant in elite soccer plays 34 games per year, and training intensity levels have increased to match the increased requirement to have fitter and faster players.

In essence, the purpose of soccer would be to kick a ball into a goal to score a point. To do this the ball has to be held within the field of play (which holds 11 players per group) with just the goalkeeper permitted to handle the ball within the area of play.

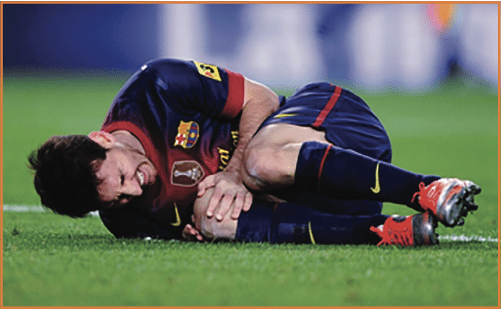

The game requires endurance, speed, agility, power and leaping ability, along with a robust musculoskeletal system to defy the rate, turning/pivoting and contact components of the sport. Therefore injury levels in football are high and harms are mostly limited to the lower limb. Interestingly, the amount of potential studies into the epidemiology of professional soccer is relatively sparse. On the other hand, the professional bodies governing the English Premier League (EPL) and the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) perform conduct long- term harm audits in their respective jurisdictions.

Profile Of A Modern Professional Player

What they found over the seven decades of data set was that the ordinary player played 34 games annually and engaged in 162 training sessions. The mean overall per year was determined to be 213 hours of instruction and 41 match hours.

It is anticipated that on average each player will endure at least two injuries during the course of the season that will necessitate removal from play or training for a minimum of one day; along with also an elite group of 25 players may expect about 50 accidents per season with half of these minor and resulting in fewer than seven days' absence.

A previous study conducted by Hawkins et al (2001) on 91 English football clubs (spread over four branches) over a two-year period found trauma rates to be less at just 1.3 accidents per player in a season normally. They also discovered that slight (two to three times) to moderate injuries (four to seven times) accounted for 68 percent of injuries and acute injuries (more than 28 months) accounted for 9 percent of accidents. Hawkins et al (2001) concluded that handling, being handled and collisions accounts for 38 percent of complete injuries and the remaining 62 percent of injuries are a consequence of non-contact mechanisms.

This is quite similar to studies in rugby union (Brookes et al 2005) who also have found that slight injuries (fewer than seven times) account for more than half the total injuries (54%).

Injury Attributes

Very similar to cohort research in rugby union (Brookes et al 2005), it's evident that game accidents account for the vast majority of injuries suffered by the elite professional player in comparison with instruction. Ekstrand et al at 2011 concluded that although coaching time much outweighed playing/match time a year (212 versus 41 hours) over half (57%) of injuries were really match-related. This represents a significant weighting towards match associated injuries when exposure time is believed (about a seven-fold growth when exposure time is a variable).This is encouraged by Hawkins et al (2001) who found that 34 percent of harms were training-related but match injuries accounted for 63%. Interestingly, foul play in games accounted for 21% of those injuries such as ankle sprains, knee sprains and contusions in the Ekstrand study. Not enough for soccer, 87 percent of all injuries were related to the lower limb. The breakdown of those injuries are as follows (Ekstrand et al 2011):

- Thigh injuries 17% (hamstring 12% and quadriceps 5%)

- Adductor strain 9%

- Ankle sprain 5%

- Medial ligaments injuries (MCL) 5%.

- Thigh 23% (hamstrings being two-thirds more common than quadriceps).

- Knee 17%

- Ankle 17%

- Lower leg 12%

- Groin 10%

1. It involves very little upper-body contact compared to other sports such as rugby and gridiron, therefore trauma and upper limb injuries are therefore relatively uncommon.

2. Footballers cover significant mileage in a game. Prozone data of players in the EPL show that midfield players can cover 10-12km a game, with 1.5km of that at light sprinting to full sprint.

3. Footballers sometimes have to play twice in a week with little recovery between matches.

4. Footballers tend to have very short preseasons due to the competition running into late May, and most clubs will have marketing trips and exhibition matches as part of their pre-season build-up through July. Therefore the opportunity to develop soft-tissue conditioning is limited.

3. Footballers sometimes have to play twice in a week with little recovery between matches.

4. Footballers tend to have very short preseasons due to the competition running into late May, and most clubs will have marketing trips and exhibition matches as part of their pre-season build-up through July. Therefore the opportunity to develop soft-tissue conditioning is limited.

Injury Variance

Ekstrand et al (2011) found that it was more common to suffer traumatic match injuries the more the pliers wore on, possibly suggesting that fatigue is connected to these injury injuries. Also, they discovered that at the pre-season (July and August), overuse-type accidents predominated; and also in season, (September to May) trauma accidents seemed to summit. This concurs with the prior work by Hawkins et al (2001) who also found that injury rates were highest in the first portion of the year and dropped off since the year wore on. Furthermore, they discovered that injury rates are somewhat more common in the past 15 minutes of their first half and last 30 minutes of the next half.It's been postulated that the well-funded European teams have well-resourced medical/rehabilitation personnel allowing for much more personalized rehabilitation of individual players. It is not uncommon for top English clubs to possess four full time physios and four full-time therapists for a group of 25 players.

Interestingly, a player suffering an accident in a year has a three-fold increase in suffering another injury (new injury unrelated to the initial) throughout the subsequent season. This has implications not only for full and appropriate treatment but also for clubs registering players moving from 1 club to another (in Ekstrand 2008).

Hamstring Injuries

Woods et al (2004) provides a comprehensive analysis of hamstring injuries over a two-year period using four divisions of English players.

From this hamstring injury study, they also found that:

1. 57% were from running and around 15% from stretching.

2. Each club sustained an average of five hamstring injuries per season.

3. Peak incidence of training injuries was in July-August (pre-season)

4. Peak incidence of match injuries was November and January.

5. Only 5% were investigated with MRI.

6. 67% occurred in match play.

7. Almost half (47%) of the injuries occurred in the last third of each half.

8. Reinjury rate for hamstrings was 12%.

9. Biceps femoris was the most frequently injured hamstring.

1. 57% were from running and around 15% from stretching.

2. Each club sustained an average of five hamstring injuries per season.

3. Peak incidence of training injuries was in July-August (pre-season)

4. Peak incidence of match injuries was November and January.

5. Only 5% were investigated with MRI.

6. 67% occurred in match play.

7. Almost half (47%) of the injuries occurred in the last third of each half.

8. Reinjury rate for hamstrings was 12%.

9. Biceps femoris was the most frequently injured hamstring.

Prevention Of Injuries In Soccer

It is unrealistic to expect that all contact- established accidents (from tackling, being tackled and crashes) are avoidable. Whenever crashes at high speed are involved, the possibility of injury exists. Therefore, ankle and knee ligament injuries, though not common in soccer, are basically contact- based injuries and the potential for injury is down to pure chance. However, a percentage of those ankle/knee injuries will probably be non-contact-related and due to twisting/ turning in non-contact situations. Ankle and knee proprioceptive programs are generally used as part of 'pre-hab' in group sports and potentially they may reduce injury risk, particularly re-injury hazard.Injuries such as hamstrings and quadriceps injuries may be deemed as being preventable and laborious because the majority of these are endured in non-contact situations. So active steps that a professional soccer program may implement to Prevent soft-tissue Injuries like hamstrings, quadriceps and hamstrings really are as follows and will be discussed individually:

1. Recognizing ‘red flag’ players

Part of the early pre-season monitoring will include a thorough medical examination and past injury history summary. The risk factors for hamstring injuries that will ‘red flag’ a player as being a potential for hamstring injury are:a. Age. Older athletes tend to suffer higher incidence of hamstring injuries.

b. Previous hamstring injury also increases the chance of another injury.

c. Associated pathology such as lumbar spine disc injuries, sacroiliac joint injuries and sciatic nerve

injuries.

d. Players returning from lengthy lay-off periods where they have not been able to run.

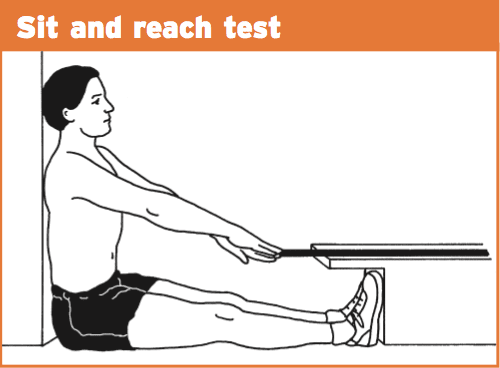

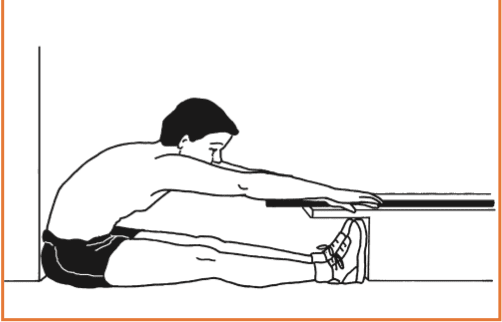

2. Musculoskeletal monitoring

Daily or next day measures that may be useful in catching players That Are showing subclinical signals include:

a. Sit and reach tests. If done regularly a baseline range of movement may be recorded. If the athlete falls out of the window of normal range, then measures need to be introduced to find out why and treatment instituted to correct this. Sit and reach is a basic measure of spine/ hip/ hamstring/neural flexibility.

b. Pelvic assessments. Joint play tests of the sacroiliac joints can pick up if players are starting to ‘tighten’ or ‘tone’ through the pelvic girdle muscles. This can have implications for motor patterns in the lower limb including hamstrings/groins/ quadriceps.

c. Strength tests. Isometric tests with a dynamometer in hamstring loading positions can help identify if players are losing strength in the hamstrings. These can be compared on a regular basis to pre-existing data for that player. Similarly, hand-held dynamometer studies on adductor strength have been shown to be useful in predicting the onset of exercise- related groin pain.

d. Range of motion tests. Verralletal (2005) have shown how decreasing levels of hip internal rotation usually precede the onset of groin pain. Again, second daily monitoring will be useful in identifying players who have started to lose hip rotation and as a result may become predisposed to groin pain.

e. Muscle tone. Massage staff can be instructed to grade the feel of the muscle tone through hamstrings/calves/ quadriceps/adductors. Again, if things change compared to the normal for that player, they will need to be assessed and treated to clear the tone changes.

3. Fatigue monitoring

Expensive monitoring units have now been developed and promoted as the new kingdom of quantifying biological markers of exhaustion. Systems like the Omegawave system use sophisticated screens on the athlete such as ECGs, muscle and brain detectors to rapidly collect information on an athletes' biological profile like heart- rate variability, cardiac readiness, hormonal readiness and fundamental system readiness.4. Periodization and planning

The problem most professional soccer teams face is adequately preparing and planning training loads throughout this season. The pressure of numerous tournaments and enjoying twice-weekly games makes it difficult to strategy overload progressions throughout this season. As an instance, a high degree EPL team for example Chelsea will play 38 Premiership matches a year, six matches in the Champions League pool phases and maybe up to three games in the FA Cup. This represents at least 47 games available to be played during the competitive season.On average, players will play around 34 games at the year with injuries, form and enforced rest which makes it improbable that players will participate in all matches. However, during a trying period of the season such as Champions League finals stages and high-priority EPL matches, players might want to play with 4-5 times in a two-week period, it's these dividers of high-intensity games back to back in which the player is the most susceptible to soft-tissue injuries.

But, top-performing teams such as Chelsea have the human resources to rotate players throughout the season for games; therefore, it makes it less likely to make soft-tissue fatigue in these players.

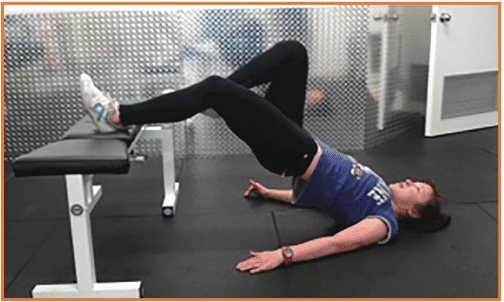

5. Preventative strength training.

Players in the elite level are not known for their tendency to being gym junkies. The contemporary elite players' perception is that weight training will 'slow you down' and my resources in elite degree EPL soccer inform me that the non-English players tend to harbor this belief that the most. Thus, having multimillion pound players get to the whole preventative health strengthening may be a difficult sell for the rehab and performance personnel. I'm advised, however, that long-term injured players are more likely to agree to a time of strength training as part of the rehabilitation procedure.However, some simple bodyweight-type exercises may be used from the soft tissue preparation of the player. These just need to be carried out once per week, instead of the conclusion of a session if the player has no match to perform the following day and they can manage to carry some tissue soreness. This small circuit can be performed post-training and will take no more than 15 minutes.

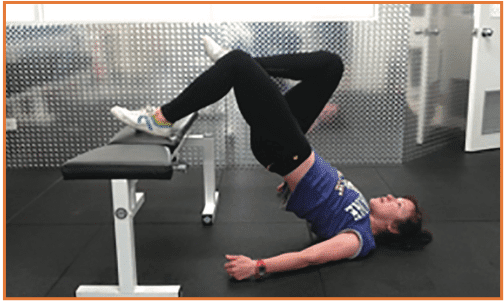

a. Bridge at 0 degrees

Start with the heel on a bench and the knee straight. Hold the other leg in flexion so that the foot is in contact with the inside of the knee. Lift the hip off the ground until the body is horizontal. Perform one set of 15 repetitions.

Start with the heel on a bench and the knee straight. Hold the other leg in flexion so that the foot is in contact with the inside of the knee. Lift the hip off the ground until the body is horizontal. Perform one set of 15 repetitions.

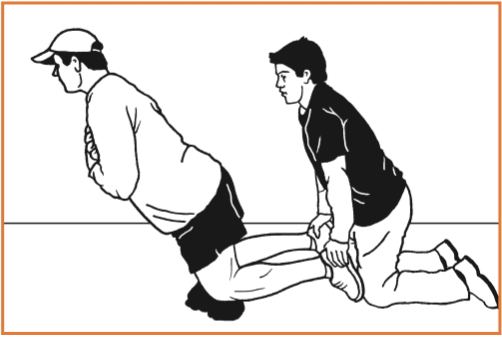

d. Nordic hamstring exercises

There exists some research Brooks et al. (2006) show that this exercise is a great preventer of hamstring injuries as well as a strengthening exercise post-injury.

There exists some research Brooks et al. (2006) show that this exercise is a great preventer of hamstring injuries as well as a strengthening exercise post-injury.

This is a great screening test to determine if an athlete is sufficiently strong to return to sport. If the athlete can perform three sets of six then this demonstrates significant hamstring strength.

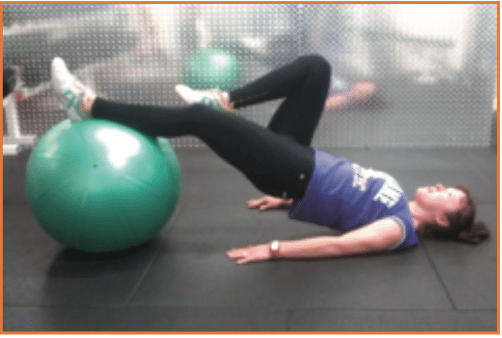

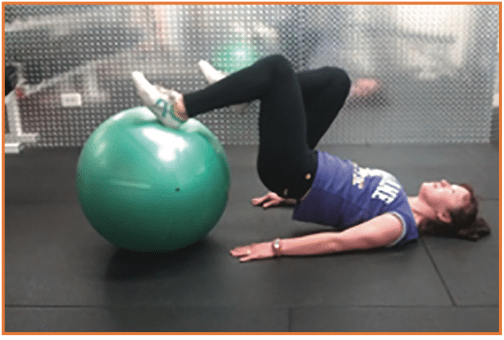

The athlete places a foot on the Swiss ball and drags the ball back towards the hips until the knee reaches 90 degrees flexion. They then slowly extend again back to the start position. The extension places significant load on the hamstring. Minimize this to one set of 10 repetitions.

Conclusion

Soccer is a fast, dynamic and possibly injurious sport played all over the world with top level athletes making large sums of money for their capacity to have the ability to kick a ball into a target. Injury rates, although generally not severe, are common in most players within a group.Research highlights the way the lower limb is the most susceptible area, and in particular delicate tissue thigh injuries -- hamstrings and quadriceps -- would be the most usual.

Although time missing from play is reasonably small, preventative steps in the kind of frequent monitoring and screening in addition to scheduled rest periods coupled with some small quantity preventative exercises appear the best way to manage soft tissue injuries from the soccer player.

References

Ekstrand et al (2011) Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: the UEFA injury study. Br J of Sports Medicine. 45; 553-558.

Woods et al (2004).The football association medical research programme: an audit of injuries in professional football – analysis of hamstring injuries. Br J of Sports Med. 38: 36-41.

Hawkinset al (2001) The association football medical research programme: an audit of injuries in professional football. Br J of Sports Med. 35: 43-47.

Ekstrand J (2008) Epidemiology of football injuries. Science and Sports. 23. 73-77.

Brookeset al (2005) Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union: part 1 match injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 39; 757-766.

Brookeset al (2005) Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union: part 2 training injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 39; 767-775.

Verrallet al (2005) Hip joint range of motion reduction in sports related chronic groin injury diagnosed as pubic bone stress injury. J Sci Sport; 8:1 77-84.

Brookset al (2006) Incidence, risk, and prevention of hamstring muscle injuries in professional rugby union. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 34(8) 1297-1306.